Charles de Bovelles

Charles de Bovelles (Latin: Carolus Bovillus; born c. 1475 at Saint-Quentin, died at Ham, Somme after 1566) was a French mathematician and philosopher, and canon of Noyon. His Géométrie en françoys (1511) was the first scientific work to be printed in French.

Bovelles authored a number of philological, theological and mystical treatises, and has been reckoned to be "perhaps the most remarkable French thinker of the 16th century."[1]

Life

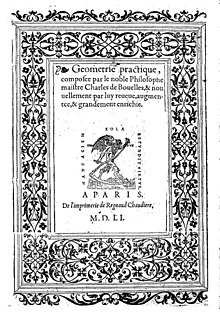

[edit]He studied arithmetic under Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples. His contemporaries knew him as widely travelled in Europe. It is known that he made a rebus for the year (1509) of the building of the hôtel de ville in Saint-Quentin. He gave a stained glass window in the town in 1521. In 1547, in the preface of La Geometrie practique, Bovelles acknowledges help from Oronce Fine with the engravings.

Maupin (end of nineteenth century) assigned dates 1470-1553, which confused many people subsequently. S. Musial in a careful study published in the Actes of the 500th centennial of his birth in Noyon in 1979 (published 1982) fixes the date of his death at 1567 (see also Margolin's Letters and Poems of Charles de Bovelles, 2002).

Works

[edit]

- In artem oppositorum introductio, 1501;

- Metaphysicae introductorium, 1503;

- De constitutione et utilitate artium, ca. 1510;

- Quae in hoc volumine continentur: Liber de intellectu. Liber de sensibus. Liber de generatione. Libellus de nihilo. Ars oppositorum. Liber de sapiente. Liber de duodecim numeris. Philosophicae epistulae. Liber de perfectis numeris. Libellus de mathematicis rosis. Liber de mathematicis corporibus. Libellus de mathematicis supplementis, 1510 (Repr. 1970);

- Dominica Oratio tertrinis ecclesiastice hierarchie ordinibus particulatim attributa et facili explanata commentario, 1511;

- In hoc opere contenta: Commentarius in primordiale Evangelium divi Joannis. Vita Remundi eremitae. Philosophicae aliquot Epistolae, 1511;

- Physicorum Elementorum libri decem denis capitibus distincti, quae capita denis sunt propositionibus exornata, unde libri sunt decem, capita centum, propositiones mille, 1512;

- Questionum theologicarum libri septem, 1513;

- Theologicarum Conclusionum libri decem, 1515;

- Responsiones ad novem quaesita Nicolai Paxii, 1520;

- Aetatum mundi septem supputatio, 1520;

- In hoc opere contenta: Liber cordis. Liber propriae rationis. Liber substantialium propositonum; Liber naturalium sophismatum. Liber cubicarum mensularum, 1523;

- Divinae Caliginis liber, 1526;

- Opus egregium de voto, libero arbitrio ac de differentis orationis, Paris 1529; Proverbiorum vulgarium libri tres, 1531;

- De Laude Hierusalem liber unus. Eiusdem de laude gentium liber I. De Concertatione et area peccati liber I. De Septem vitiis liber I, 1531;

- De Raptu divi Pauli libellus, auctus ab eius epistula ad fratrem Innocentium Guenotum, in Caelestinesium monarchorum ordine Deo militantem. Eiusdem de Prophetica Visione liber, 1531;

- Liber de differentia vulgarium linguarum et gallici sermonis varietate, 1533;

- Agonologia Christi, 1533;

- Dialogi tres de Animae immortalitate, Resurrectione, Mundi excidio et illius instauratione, 1552;

- Geometricum opus duobus libris comprehensum, 1557;

- Praxilogia Christi quatuor libris distincta. o. J.

His first major work, Quæ in hoc volumine (1510/11), a collection of 12 works by Bovelles that constitute a major but still little recognized contribution to the philosophical thought of the Renaissance. Of these 12 works, the Liber de Sapiente is certainly the most significant, serving to summarize and synthesize the ideas presented in the other short treatises. In fact, the Liber de Sapiente is the only part of In Hoc Volumine that has had a modern edition having been translated once into Italian and twice into French. And yet this work still has no English translation. The Liber de sapiente is important to intellectual history because it exemplifies the transition between Medieval and Renaissance thinking. Ernst Cassirer considered the Liber de Sapiente, "perhaps the most curious and in some respects the most characteristic creation of Renaissance philosophy … [because] in no other work can we find such an intimate union of old and new ideas." (1927, p. 88). Cassirer even included a critical Latin edition of the de Sapiente prepared by his student as an appendix to The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy.

In geometry, Bovelles was a Pythagorean: objects and living beings take up regular shapes. Some of his chapters, on bells, physiognomy, machines, are representative of the period.

Michel Chasles, in his Aperçu historique... des méthodes en géométrie, points out Bovelles for his work on star polyhedra, a successor in this of Thomas Bradwardine.

- Quæ in hoc volumine continentur... mathematicum opus quadripartitum : de numeris perfectis, de mathematicis rosis, de geometricis corporibus, de geometricis complementis (1510), printer Henri Estienne, Paris

- Géométrie en françoys (1510/11), Henri Estienne, Paris

- Livre singulier & utile touchant l'art et practique de Géométrie, composé nouvellement en Françoys, par maistre Charles de Bouelles (1542)

- La Geometrie practique, composee par le noble Philosophe maistre Charles de Bovelles (1547, reprint 1566), Guil. de Marnef, Paris

- Le Livre du Sage, trad. P. Magnard, éd. Vrin, Paris, 1982.

- Le Livre du Néant, trad. P. Magnard, éd. Vrin, Paris, 1983.

- L'art des opposés, trad. P. Magnard, éd. Vrin, Paris, 1984.

His 1533 work Agonologiae Jesu Christi, libri quatuor has been cited in art history. For example, John North, The Ambassadors' Secret (2002), refers to it (p. 179, and elsewhere), in interpreting Holbein's picture The Ambassadors.

References

[edit]- ^ Albert Rivaud. Cf. French Wikipédia article.

- Tamara Albertini, Charles de Bovelles: Natura e Ragione come spazio interno/esterno della conoscenza, in L'uomo e la Natura nel Rinascimento, Firenze 1998

- Ernst Cassirer, Individu et cosmos dans la philosophie de la Renaissance (1983), éd. de Minuit, Paris ISBN 2-7073-0648-7

- Cesare Catà, L'abisso come origine. Portata e significati del concetto di "nulla" nel De Nihilo di Charles de Bovelles, (forthcoming)

- Cesare Catà, Forking Paths in Sixteenth-Century Philosophy: Charles de Bovelles and Giordano Bruno, in Viator. Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA University, Volume 40, No. 2 (2009)

- Emmanuel Faye, "L'idée de l'homme dans la philosophie de Charles de Bovelles", in Philosophie et perfection de l'homme. De la Renaissance à Descartes, Paris, Librairie J. Vrin, « Philologie et Mercure » 1998, pp. 73–160 ISBN 2-7116-1331-3.

- G. Maupin, Opinions et curiosités touchant la Mathématique d'après les ouvrages français des XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Bibliotheèque de la Revue Générale des Sciences, Paris, Carré et Naud, 1898.

- S. Musial, Dates de naissance et de mort de Charles de Bovelles » dans « Charles de Bovelles en son cinquième centenaires 1479-1979 - Éditions Trédaniel 1982.

- P. M. Sanders, Charles de Bovelles's treatise on the regular polyhedra (Paris, 1511), Annals of Science, Volume 41, Issue 6 November 1984, pp. 513 – 566

- Joseph M. Victor, Charles de Bovelles, 1479-1553: An Intellectual Biography Genève: Droz, 1978.

External links

[edit]- Charles de Bovelles: The Book on the Sage -- English translation of chapters 1-8 and 22-26

- Dominik Bertrand-Pfaff (2003). "Bouelles, Charles de (auch Bouvelles, Bovelles, Bouillé, Bouilles oder latinisiert: Carolus Bovillus)". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 21. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 149–154. ISBN 3-88309-110-3.