Colorado River toad

| Colorado River toad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | I. alvarius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Incilius alvarius | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ollotis alvaria (Frost, 2006) | |

The Colorado River toad (Incilius alvarius), also known as the Sonoran Desert toad, is a psychoactive toad found in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. Its toxin, as an exudate of glands within the skin, contains 5-MeO-DMT and bufotenin.

Description

The Colorado River toad can grow to about 7.5 inches (190 mm) long and is the largest toad in the United States apart from the non-native cane toad (Rhinella marina). It has a smooth, leathery skin and is olive green or mottled brown in color. Just behind the large golden eye with horizontal pupil is a bulging kidney-shaped parotoid gland. Below this is a large circular pale green area which is the tympanum or ear drum. By the corner of the mouth there is a white wart and there are white glands on the legs. All these glands produce toxic secretions.

Dogs that have attacked toads have been paralyzed or even killed. Raccoons have learned to pull a toad away from a pond by the back leg, turn it on its back and start feeding on its belly, a strategy that keeps the raccoon well away from the poison glands.[2] Unlike other vertebrates, this amphibian obtains water mostly by osmotic absorption across their abdomen. Toads in the family bufonidae have a region of skin known as "the seat patch", which extends from mid abdomen to the hind legs and is specialized for rapid rehydration. Most of the rehydration is done through absorption of water from small pools or wet objects.[3]

Distribution and habitat

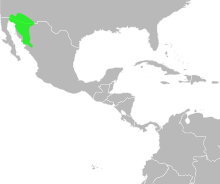

The Colorado River toad is found in the lower Colorado River and the Gila River catchment areas, in southeastern California, New Mexico, Mexico and much of southern Arizona. It lives in both desert and semiarid areas throughout its range. It is semiaquatic and is often found in streams, near springs, in canals and drainage ditches, and under water troughs.[2] The Bufo alvarius is known to breed in artificial water bodies (e.g., flood control impoundments, reservoirs) and as a result, the distributions and breeding habitats of these species may have been recently altered in south central Arizona.[4] It often makes its home in rodent burrows and is nocturnal. Its call is described as, "a weak, low-pitched toot, lasting less than a second."[5]

Biology

Bufo alvarius is sympatric with the spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus spp.), Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus), red-spotted toad (Bufo punctatus), and Woodhouse's toad (Bufo woodhousei). Like many other toads, they are active foragers and feed on invertebrates, lizards, small mammals, and amphibians. The most active season for toads is May–September, due to greater rainfalls (needed for breeding purposes). The age of B. alvarius ranges from 2 to 4 years within a population at Adobe Dam in Maricopa County, Arizona; however, other species in the toad family have a longer lifespan of 4 to 5 years.[6] The taxonomic affinities of B. alvarius remain unclear, but immunologically, it is equally close to the boreas and valliceps groups.[7]

Breeding

The breeding season starts in May, when the rainy season begins, and can last up to August. Normally, 1–3 days after the rain is when toads begin to lay eggs in ponds, slow-moving streams, temporary pools or man-made structures that hold water. Eggs are 1.6 mm in diameter, 5–7 cm apart, and encased in a long single tube of jelly with a loose but distinct outline. The female toad can lay up to 8,000 eggs.[8]

Drug use of poison

The toad's primary defense system are glands that produce a poison that may be potent enough to kill a grown dog.[9] These parotoid glands also produce the 5-MeO-DMT [10] and bufotenin for which the toad is known; both of these chemicals belong to the family of hallucinogenic tryptamines. Although 5-MeO-DMT is known to be toxic when consumed orally, this chemical may be safely smoked and is powerfully psychoactive. After inhalation user usually experience a warm sensation, euphoria, and strong auditory hallucinations. No long-lasting effects have been reported.[11]

State laws

The toads received national attention after a story was published in the New York Times Magazine in 1994 about a California teacher who became the first person to be arrested for possessing the venom of the toads.[12][13] The substance concerned, bufotenin, had been outlawed in California in 1970.[14]

In November 2007, a man in Kansas City, Missouri was discovered with an I. alvarius toad in his possession, and charged with possession of a controlled substance after they determined he intended to use its secretions for recreational purposes.[15][16] In Arizona, one may legally bag up to 10 toads with a fishing license, but it could constitute a criminal violation if it can be shown that one is in possession of this toad with the intent to smoke its venom.[17]

None of the states in which I. alvarius is (or was) indigenous – California, Arizona, and New Mexico – legally allows a person to remove the toad from the state. For example, the Arizona Game and Fish Department is clear about the law in Arizona: "An individual shall not... export any live wildlife from the state; 3. Transport, possess, offer for sale, sell, sell as live bait, trade, give away, purchase, rent, lease, display, exhibit, propagate... within the state..."[17]

In California, I. alvarius has been designated as "endangered" and possession of this toad is illegal. "It is unlawful to capture, collect, intentionally kill or injure, possess, purchase, propagate, sell, transport, import or export any native reptile or amphibian, or part thereof..."[18]

In New Mexico, this toad is listed as "threatened" and, again, taking I. alvarius is unlawful.[19][20]

References

- ^ Hammerson, Geoffrey and Santos-Barrera, Georgina (2004). Incilius alvarius. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2

- ^ a b Badger, David; Netherton, John (1995). Frogs. Shrewsbury, England: Swan Hill Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 1 85310 740 9.

- ^ Zoological Science. Zoological Society of Japan. pp. 664–670.

- ^ "Copeia". Natural Hybridization among Distantly Related Toads (Bufo alvarius, Bufo cognatus, Bufo woodhousii) in Central Arizona. 1999: 281–286. 1999. doi:10.2307/1447473.

- ^ National Audubon Society: Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians

- ^ "Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Program". September 2008: 330–342.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Herpetologica". Call Variation in the Colorado River Toad (Bufo alvarius): Behavioral and Phylogenetic Implications. 50: 146–156. 1994.

- ^ Behler, J.L. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Knopf; 1 edition (November 12, 1979). p. 743. ISBN 0394508246.

- ^ Phillips, Steven J.; Wentworth Comus, Patricia, eds. (2000). A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. University of California Press. p. 537. ISBN 0-520-21980-5.

- ^ Toxins of Bufo alvarius

- ^ "Identity of a New World Psychoactive Toad". Ancient Mesoamerica. 3 (01): 51–59. March 1992. doi:10.1017/s0956536100002297.

- ^ "Missionary for Toad Venom Is Facing Charges". New York Times. 20 February 1994.

- ^ "Couple Avoid Jail In Toad Extract Case". New York Times. 1 May 1994.

- ^ Bernheimer, Kate (2007). Brothers & beasts: an anthology of men on fairy tales. Wayne State University Press. pp. 157–159. ISBN 0-8143-3267-6.

- ^ "'Toad Smoking' Uses Venom From Angry Amphibian to Get High". FOX News. Kansas City. 3 December 2007.

- ^ Shelton, Natalie (7 November 2007). "Drug sweep yields weed, coke, toad". KC Community News. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 14 December 2007 suggested (help) - ^ a b AZGFD.gov

- ^ "Title 14. Division 1. Subdivision 1. Chapter 5., § 40(a)".

- ^ 19.33.6 NMAC. nmcpr.state.nm.us

- ^ 19.35.10 NMAC. nmcpr.state.nm.us

Further reading

- Pauly, G. B., D. M. Hillis, and D. C. Cannatella. (2004) The history of a Nearctic colonization: Molecular phylogenetics and biogeography of the Nearctic toads (Bufo). Evolution 58: 2517–2535.

- Frost, Darrel R.; Grant, Taran; Faivovich, JuliÁN; Bain, Raoul H.; Haas, Alexander; Haddad, CÉLIO F.B.; De SÁ, Rafael O.; Channing, Alan; Wilkinson, Mark; Donnellan, Stephen C.; Raxworthy, Christopher J.; Campbell, Jonathan A.; Blotto, Boris L.; Moler, Paul; Drewes, Robert C.; Nussbaum, Ronald A.; Lynch, John D.; Green, David M.; Wheeler, Ward C.; et al. (2006). "The Amphibian Tree of Life". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 297: 1–370. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2006)297[0001:TATOL]2.0.CO;2.

External links

- AmphibiaWeb: Biology and Conservation Information

- NatureServe: Conservation Data

- CaliforniaHerps.com: Documenting California's indigenous reptiles and amphibians

- Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

- Sonoran Desert Toad – Natural History site

- Toad-smoking gains on toad-licking among drug users- Wall Street Journal

- Secretions From Colorado Toad Contain Powerful Psychedelic Compound- NSDN

- Erowid Psychoactive Toad Vault

- Arizona: Tucson Herpetological Society – beautiful pictures