Enduring Love

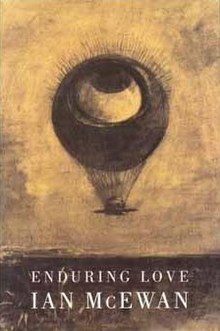

First-edition hardback cover | |

| Author | Ian McEwan |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Odilon Redon, "The eye like a strange balloon mounts toward infinity", 1882[1] |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 1997 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 247 pp |

| ISBN | 0-224-05031-1 (first edition) |

| OCLC | 37706997 |

Enduring Love is a 1997 novel by British writer Ian McEwan. The plot concerns two strangers who become perilously entangled after witnessing a deadly accident.

Summary

[edit]On a beautiful and cloudless day, a middle-aged couple celebrate their union with a picnic. Joe Rose, aged 47, and his long-term partner Clarissa Mellon are about to open a bottle of wine when a cry interrupts them. A helium balloon, with a ten-year-old boy in the basket and his grandfather being dragged behind it, has been ripped from its moorings. Joe immediately joins several other men in an effort to bring the balloon to safety. In the rescue attempt one man, John Logan, a doctor, dies.

Another of the would-be rescuers is Jed Parry. Joe and Jed exchange a passing glance, a glance which indelibly burns an obsession into Jed's soul and has devastating consequences, for Jed suffers from de Clerambault's syndrome, a disorder that causes the sufferer to believe that someone is in love with him or her. Delusional and dangerous, Jed gradually wreaks havoc in Joe's life, testing the limits of his beloved rationalism, threatening Clarissa's love for him, and driving him to frustration.

Joe goes to meet Jean Logan (John Logan's wife) at her Oxford home. Jean Logan does not want to hear about how her husband was a hero, but Joe tells her that her husband was a brave man acting out a fatherly instinct to protect a vulnerable child. Mrs Logan hands Joe a bag which holds a picnic, and then hands him a scarf smelling of rose-water, and asks Joe how many doors were open on Logan's car. She accuses her dead husband of having an affair with another woman and asks Joe to phone other people who were present at the accident to ascertain if they had seen anyone with Logan. She says her husband was a cautious man and probably only died because he was showing off to the woman, trying to prove his manliness, and thereby taking unnecessary risks, rather than hanging back and staying safe.

During a lunch with Clarissa and her godfather, Joe witnesses the attempted murder of a man seated at a table next to theirs, resulting in the man being shot in the shoulder. However, Joe realises the bullet was meant for himself and the similar composition of the group of people at the other table misled the two killers into thinking the other man was their target. Before the hit man can deliver the fatal shot Jed Parry intervenes to save the innocent man's life before fleeing the scene. In the subsequent police interview Joe insists that it was Jed Parry who was behind this attack, but the detective does not believe him, possibly because Joe appears to get some of the facts of the incident incorrect. Joe leaves dissatisfied, knowing that Jed is still out there and looking for him. Like the detective, however, Clarissa is sceptical that Jed is stalking Joe and that Joe is in any danger. This, plus the stress Joe suffers at Jed's hands, strains their relationship.

Fearing for his safety, Joe purchases a gun through an acquaintance, John Well. On the journey home Joe receives a phone call from Jed Parry, who is at Joe's home with Clarissa. Upon arriving at his apartment, Joe sees Jed sitting on the sofa with Clarissa. Jed then asks for Joe's forgiveness, before taking out a knife and pointing it at his own neck. To prevent Jed from killing himself, Joe shoots him in the arm.

Joe and Clarissa go to meet Mrs Logan. They take her and her two infant children on a picnic next to a river, to which they have invited the woman her husband was suspected of having an affair with. It turns out that on the day of the balloon accident the young woman had been with a university lecturer, thirty years her senior, with whom she was having a secret relationship; Dr Logan had simply offered them both a ride after the lecturer's car had broken down. The novel ends with the two Logan children and Joe beside the river, Joe telling the children a story about how the river is made up of many particles.

In the first of the novel's appendices (a medical report on Jed's condition) we learn that Joe and Clarissa are eventually reconciled, and that they adopt a child. In the second appendix (a letter from Jed to Joe) we learn that even after three years Jed remains uncured and is now living in a psychiatric hospital.

Reception

[edit]Upon release, Enduring Love was generally well received. According to Book Marks, the book received "positive" reviews based on ten critic reviews with three being "rave" and six being "positive" and one being "mixed".[2]

Adaptations

[edit]In 2004, Enduring Love was adapted into a film of the same name. The film version was directed by Roger Michell, written by Joe Penhall, and starred Daniel Craig, Rhys Ifans and Samantha Morton, with Bill Nighy, Susan Lynch and Corin Redgrave. The film received mixed reviews from critics, and the popular movie review site Rotten Tomatoes gave the movie a rating of 59% positive reviews.

In 2023, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a dramatization written by Kate Clanchy, starring Blake Ritson and Hattie Morahan, and produced and directed by Amber Barnfather.[3]

Fictional appendix

[edit]The book contains an appendix purporting to be a scientific paper ("A Homo-Erotic Obsession, with Religious Overtones: A Clinical Variant of de Clerambault's Syndrome") describing a case study identical to the one around which the narrative is based. The appendix is an invention of McEwan, with its authors – Wenn and Camia – being an anagram of his name. Although fictional, some reviewers took the document to be a factual case, with a review in The New York Times criticizing McEwan for having "simply stuck too close to the facts".[4]

McEwan later submitted the paper to the British Journal of Psychiatry under the name of the paper's fictional writers,[5] but it was not published. Speaking in 1999, McEwan said "I get four or five letters a week, usually from reading groups but sometimes from psychiatrists and scholars, asking if I wrote the appendix."[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "P29 – Research 3 – Odilon Redon". The Milkman Goes To College. 23 September 2012.

- ^ "Enduring Love". Book Marks. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ Enduring Love – Drama – BBC Radio 4

- ^ a b The Guardian, 16 August 1999.

- ^ "Doctors Wenn and Camia, I Presume? Inside Ian McEwan's papers". Cultural Compass. 24 August 2023.

...and in case the web page that goes with the preceding "external link" -- (which might be extant only as an "archived" copy, now) -- is lacking the .jpg (photograph) files that properly belong with that "doctors-wenn-and-camia-i-presume-inside-ian-mcewans-papers" document, or blog entry, or magazine article, or whatever it is, ... here is an 'alternate' or "substitute" external link, which [links to a web page that] does contain satisfactory .jpg (photograph) files:

Armstrong, Amy (15 October 2015). "Doctors Wenn and Camia, I Presume? Inside Ian McEwan's papers". Ransom Center Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

External links

[edit]- Reading Group Guide: Enduring Love

- An Interview with Ian McEwan. Bold Type, 03.1998.

- An Interview with Ian McEwan. Capitola Book Café, 16 February 1998.

- Jonathan Greenberg. "Why can't biologists read poetry? Ian McEwan's Enduring Love". Twentieth Century Literature, Summer 2007.

- Laura Miller. "Ian McEwan fools British shrinks". Salon.com, 21 Sep 1999.

- Michael Ruse. "Review of Ian McEwan's Enduring Love" Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The Global Spiral, Metanexus Institute 1999.08.01.

- Maxine E. Walker. "Ian McEwan's Enduring Love jed is obsessed with sex in a Secular Age". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, Vol. 21 (1) Spring 2009.