Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot

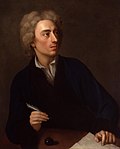

The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot is a satire in poetic form written by Alexander Pope and addressed to his friend John Arbuthnot, a physician. It was first published in 1735 and composed in 1734, when Pope learned that Arbuthnot was dying. Pope described it as a memorial of their friendship.[1] It has been called[2] Pope's "most directly autobiographical work", in which he defends his practice in the genre of satire and attacks those who had been his opponents and rivals throughout his career.[3]

Both in composition and in publication, the poem had a chequered history. In its canonical form, it is composed of 419 lines of heroic couplets.[4] The Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot is notable as the source of the phrase "damn with faint praise," used so often it has become a cliché or idiom. Another of its notable lines is "Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?"

Addressee

John Arbuthnot was a physician known as a man of wit. He was a member of the Martinus Scriblerus Club, along with Pope, Jonathan Swift and John Gay. He was formerly the physician of Queen Anne.[5] On 17 July 1734 Arbuthnot wrote to Pope to tell him that he had a terminal illness. In a response dated 2 August, Pope indicates that he planned to write more satire, and on 25 August told Arbuthnot that he was going to address one of his epistles to him, later characterizing it as a memorial to their friendship. Arbuthnot died on 27 February 1735, eight weeks after the poem was published.[6]

Composition

According to Pope, the Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot was a satire "written piecemeal many years, and which I have now made haste to put together". The poem was completed by 3 September, when Pope wrote to Arbuthnot describing the poem as "the best Memorial that I can leave, both of my Friendship to you, & of my own Character being such as you need not be ashamd of that Friendship".[7]

Publishing history

Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot has a "tangled" publishing history. The poem was first published as a folio of 24 pages on 2 January 1735 under the title An Epistle from Mr. Pope to Dr. Arbuthnot, with a date of 1734. It appeared in Pope's Works the same year in folio, quarto and octavo, with a Dublin edition and an Edinburgh piracy. During Pope's lifetime, it was included among the Moral Essays. In 1751, after the death of Pope, it was published at the beginning of Imitations of Horace and retitled Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot, being the Prologue to the Satire, even though it lacks both Horatian and prologic characteristics.[8]

Analysis

The poem includes character sketches of "Atticus" (Joseph Addison) and "Sporus" (John Hervey). Addison is presented as having great talent that is diminished by fear and jealousy; Hervey is sexually perverse, malicious, and both absurd and dangerous.[9] Pope marks the virulence of the "Sporus" attack by having Arbuthnot exclaim "Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?" in reference to the form of torture called the breaking wheel.[10] By emphasizing friendship, Pope counters his image as "an envious and malicious monster" whose "satire springs from a being devoid of all natural affections and lacking a heart."[11] It was an "efficient and authoritative revenge":[12] in this poem and others of the 1730s, Pope presents himself as writing satire not out of ego or misanthropy, but to serve impersonal virtue.[13]

Although rejected by a critic contemporary with Pope as a "mere lampoon",[14] Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot has been described as one of Pope's "most striking achievements, a work of authentic power, both tragic and comic, as well as great formal ingenuity, despite the near-chaos from which it emerged."[15]

References

- ^ Pat Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia (Greenwood Press, 2004), p. 110.

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110.

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110.

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110.

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature, volume 1.[citation needed]

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110; Baines, The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope (Routledge, 2000), p. 37.

- ^ Rogers, The Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110, citing Pope's Correspondence 3: 416–17, 423, 428, 431.

- ^ Rogers, The Pope Encyclopedia, p. 110.

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 111.

- ^ Dennis Todd, Imagining Monsters: Miscreations of Self in Eighteenth-Century England (University of Chicago Press, 1995), p. 245.

- ^ Todd, Imagining Monsters, p. 247.

- ^ Baines, The Complete Critical Guide to Alexander Pope, p. 36.

- ^ Todd, Imagining Monsters, p. 247.

- ^ John Barnard, Alexander Pope: The Critical Heritage (Routledge, 1973), p. 16.

- ^ Rogers, The Alexander Pope Encyclopedia, p. 111.