Gene delivery

Gene delivery is the process of introducing foreign DNA into host cells. Gene delivery occurs throughout nature as horizontal gene transfer from one organism to another and is a mechanism of evolution.[1] It is also one of the steps necessary for gene therapy and, for example, has applications in the genetic modification of crops. There are many different methods of gene delivery for various types of cells and tissues, from bacterial to mammalian.

For gene delivery to be successful, foreign DNA must survive long enough in the host cell to integrate into its genome. This requires foreign DNA to be synthesized as part of a vector, which is designed to enter the desired host cell and deliver the transgene to that cell's genome.[2] Vectors utilized as the method for gene delivery can be divided into two categories, non-viral and viral.[3]

In complex multicellular eukaryotes (more specifically Weissmanists), if the transgene is incorporated into the host's germline cells, the resulting host cell can pass the transgene to its progeny. If the transgene is incorporated into somatic cells, the transgene will die with the somatic cell line, and thus its host organism.[4]

Methods

Non-Viral

Non-viral methods of gene delivery can be divided into transformation, where a cell incorporates foreign DNA from it's surroundings, and conjugation, where gene transfer is a result of direct contact between two cells. Both methods utilize plasmids, which carry DNA inside a cell that can replicate independently of chromosomal DNA. This is the DNA that can be transferred to another organism. Artificial non-viral gene delivery can be mediated by physical methods such as electroporation, microinjection, gene gun, impalefection, hydrostatic pressure, continuous infusion, sonication and lipofection. It can also include the use of polymeric gene carriers (polyplexes).[5]

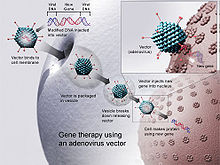

Viral

Virus mediated gene delivery utilizes the ability of a virus to inject its DNA inside a host cell. Transduction is the process through which DNA is injected into the host cell and inserted into its genome. Viruses are a particularly effective form of gene delivery because the structure of the virus prevents degradation via lysosomes of the DNA it is delivering to the nucleus of the host cell.[6] In gene therapy a gene that is intended for delivery is packaged into a replication-deficient viral particle to form a viral vector.[7] Viruses used for gene therapy to date include retrovirus, adenovirus, adeno-associated virus and herpes simplex virus. However, there are drawbacks to using viruses to deliver genes into cells. Viruses can only deliver very small pieces of DNA into the cells, it is labor-intensive and there are risks of random insertion sites, cytophathic effects and mutagenesis.[8]

Applications

In Nature

Gene delivery is an integral part of genome evolution. Genome analysis of Acanthamoeba castellanii, an amoebozoan, revealed that a significant portion of the genome that is expressed can be traced to lateral gene transfer amongst organisms. The ability of this eukaryote to host a wide range of endosymbionts allows it to interact with a wide range of DNA. When analyzed, the genome of Acanthamoeba castellanii shows genes with orthologs currently found in a diverse range of bacteria, viruses, and archaea.[9]

Gene Therapy

Several of the methods used to facilitate gene delivery in nature and research have applications for therapeutic purposes. Gene therapy utilizes gene delivery to deliver genetic material with the goal of treating a disease or condition in the cell. Gene delivery in therapeutic settings utilizes non-immunogenic vectors capable of cell specificity that can deliver an adequate amount of transgene expression to cause the desired effect.[10]

Advances in genomics have enabled a variety of new methods and gene targets to be identified for possible applications. DNA microarrays used in a variety of next-gen sequencing can identify thousands of genes simultaneously, with analytical software looking at gene expression patterns, and orthologous genes in model species to identify function.[11] This has allowed a variety of possible vectors to be identified for use in gene therapy. As a method for creating a new class of vaccine, gene delivery has been utilized to generate a hybrid biosynthetic vector to deliver a possible vaccine. This vector overcomes traditional barriers to gene delivery by combining E. Coli with a synthetic polymer to create a vector that maintains plasmid DNA while having an increased ability to avoid degradation by target cell lysosomes.[12]

See also

References

- ^ Boto, Luis (2009). "Horizontal Gene Transfer in Evolution: Facts and Challenges". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 277. The Royal Society: 819–827 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Gibson, Greg; Muse, Spencer V (2009). A Primer of Genome Science (Third ed.). 23 Plumtree Rd, Sunderland, MA 01375: Sinauer Associates. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-0-87893-236-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Kamimura K, Suda T, Zhang G, et al. (2011). "Advances in Gene Delivery Systems". Pharm Med. 25 (5): 293–306. doi:10.2165/11594020-000000000-00000.

- ^ Nayerossadat, Nouri; Maedeh, Talebi; Abas, Ali (6 July 2012). "Viral and nonviral delivery systems for gene delivery". Advanced Biomedical Research. 1: 27. doi:10.4103/2277-9175.98152. PMC 3507026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Saul JM, Linnes MP, Ratner BD, Giachelli CM, Pun SH (November 2007). "Delivery of non-viral gene carriers from sphere-templated fibrin scaffolds for sustained transgene expression". Biomaterials. 28 (31): 4705–16. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.026. PMID 17675152.

- ^ Wivel, Nelson; Wilson, James (1998). "Methods of Gene Delivery". Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 12: 483–501. PMID 9684094 – via Science Direct.

- ^ Lodish, H; Berk, A; Zipursky, SL; et al. (2000). Molecular Cell Biology (Fourth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. Section 6.3, Viruses: Structure, Function, and Uses. ISBN 9780716737063.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last4=(help) - ^ Keles, Erhan; Song, Yang; et al. (2016). "Recent progress in nanomaterials for gene delivery applications". Biomaterials Science. 4: 1291–1309. doi:10.1039/C6BM00441E – via Royal Society of Chemistry.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help) - ^ Clarke, Michael; Lohan, Amanda J; et al. (2013). "Genome of Acanthamoeba castellanii highlights extensive lateral gene transfer and early evolution of tyrosine kinase signaling". Genome Biology. doi:10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r11.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mali, Shrikant (2013). "Delivery systems for gene therapy". Indian Human Journal of Human Genetics. 19: 3–8. doi:10.4103/0971-6866.112870. PMC 3722627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Guyon, I; Weston, J; et al. (2002). "Gene Selection for Cancer Classification using Support Vector Machines". Machine Learning. 46: 389–422. doi:10.1023/A:1012487302797.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help) - ^ Jones, C; Ravikrishnan, A; et al. (2014). "Hybrid biosynthetic gene therapy vector development and dual engineering capacity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (34): 12360–12365.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help)

Further reading

- Segura T, Shea LD (2001). "Materials for non-viral gene delivery". Annual Review of Materials Research. 31: 25–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.31.1.25.

- Luo D, Saltzman WM (January 2000). "Synthetic DNA delivery systems". Nat. Biotechnol. 18 (1): 33–7. doi:10.1038/71889. PMID 10625387.