Germany–Poland border

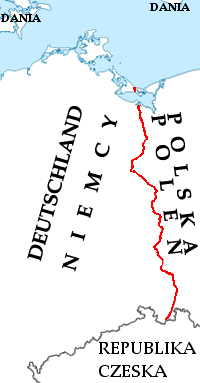

The Germany–Poland border (German: Grenze zwischen Deutschland und Polen, Polish: Granica polsko-niemiecka), the state border between Poland and Germany, is currently the Oder–Neisse line. It has a total length of 467 km (290 mi)[1] and has been in place since 1945. It stretches from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Czech Republic in the south.

History

Germany–Poland border traces its origins to the beginnings of the Polish state, with the Oder (Odra) and Lusatian Neisse (Nysa) rivers (the Oder–Neisse line) being one of the earliest natural boundaries between Germany and the Slavic tribes.[2][3][4][5][6] Over several centuries, it has moved eastwards, stabilized in the 14th century,[7] and disappeared in the late 18th century with the partitions of Poland, in which Poland's neighbors, including the Kingdom of Prussia, annexed all of its territory.[3][8][9] In 1871 Prussia became part of the German Empire.

After Poland regained independence following World War I and the 123 years of partitions,[8] a long German-Polish border was settled on, 1,912 km (1,188 mi) long (including a 607 km (377 mi) border with East Prussia).[10] The border was partially shaped by the Treaty of Versailles and partially by plebiscites (East Prussian plebiscite and the Silesian plebiscite, the former also affected by the Silesian Uprisings).[9][10][11][12] The shape of that border roughly resembled that of pre-partition Poland.[13]

After World War II, the border was drawn from Świnoujście (Swinemünde) in the north at the Baltic Sea southward to the Czech Republic (then part of Czechoslovakia) border with Poland and Germany near Zittau. It follows the Oder–Neisse line of the Oder (Odra) and Neisse (Nysa) rivers through most of their course.[14][15][dubious – discuss] This was agreed upon by the main Allies of World War II – the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom, at the Soviets' insistence, and, without any significant consultations with Poland (or Germany), at the Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference.[15][16][17] Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, replied to Mikołajczyk's question about the western border of Poland that "it should be based on the Oder River". At the summit in Yalta, the leaders of the powers decided to hand over to Poland part of East Prussia with Olsztyn and Elbląg, Pomerania with Gdańsk and Szczecin, Lower and Upper Silesia with Opole, Wrocław and Gliwice, and the Lubusz land. On July 24, for the only time in history, the communist Bierut and the oppositionist Stanisław Mikołajczyk spoke with one voice, fighting for the Oder and Western Neisse line. Churchill insisted on Eastern Neisse, which meant that Wałbrzych with its region and Jelenia Góra would remain German. Just before the final protocol was signed, Soviet diplomats made one more amendment according to which the border was to run "west of Świnoujście". Like a trifle, but thanks to this Szczecin got free access to the Baltic Sea.[18]

This border was a compensation to Poland for territories lost to the Soviet Union as a consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and resulted in significant westward transfers of German population from the "Recovered Territories".[3][16][19] It roughly matched the centuries-old, historical border between the Medieval Polish and German states.[3] It divided several river cities into two parts – Görlitz/Zgorzelec, Guben/Gubin, Frankfurt (Oder)/Słubice, Bad Muskau/Łęknica.[20]

An urgent issue in the west was the delineation of a border section from Świnoujście to Gryfino in the terrain. Until autumn 1945, these areas, except Szczecin, were not yet included in the Polish administration. This section of the border was delineated in September and October 1945 by the Polish-Soviet mixed commission. By the signed agreement, the Polish administration took over them on October 4, 1945. With the detailed demarcation of the western border, it turned out that in many places it was absurd. The statement of the Potsdam conference that the border should run "directly" west of Świnoujście was put into action so literally that even the water intake for the city of Świnoujście was left abroad. This situation meant that over the years corrections were made to the previously set border route. It was already established in September 1945 that Poland would depart from the German side of Rieth and Altwarp in exchange for Stolec, Buk, Bobolin, Barnisław, Rosówek, Pargowo and the Stobno-Kołbaskowo road. In 1949, however, the border was adjusted at the height of the intersection and the Links-Neu Lienken-Buk road. It was agreed that the entire intersection in Nowe Linky would go to the side of the German Democratic Republic, in exchange for a narrow strip of land lying directly on the west side of the road from Nowe Linki to Buk. In January 1951, an act was drawn up to delineate the border between the Polish People's Republic and the German Democratic Republic, confirming the Polish administration of the islands between the Western Oder and Regalica (Międzyodrze) south of Gryfino. In November 1950, the government of the German Democratic Republic agreed to the transfer of a water intake to Poland, located at Lake Wolgastsee. In June of the following year, an area of 76.5 ha (together with a water treatment plant) was incorporated into Poland, creating a characteristic promontory protruding into the German area. In return, a similarly-sized area north of Mescherin, including the village of Staffelde (Polish: Staw), was transferred from Poland to the German Democratic Republic.[21]

On June 6, 1950, a declaration was signed between the government of the Polish People's Republic and the German Democratic Republic on the demarcation of the existing Polish-German border on the Oder–Neisse line. After the initial agreement, both countries concluded the Treaty of Zgorzelec. The border was recognized by West Germany in 1970 in the Treaty of Warsaw, and by reunified Germany, in 1990 in the German–Polish Border Treaty of 1990.[22][23][24][25] It was subject to minor corrections (land swaps) in 1951.[25] The borders were partially open from 1971 to 1980 when Poles and East Germans could cross it without a passport or a visa; it was however closed again after a few years, due to economic pressure on the East German economy from Polish shoppers and the desire of the East German government to diminish the influence of the Polish Solidarity movement on East Germany.[26][27][28]

Following the fall of communism in Poland and Germany, and the German reunification, the border became part of the eastern border of the European Economic Community, then that of the European Union. For a period, it was "the most heavily policed border in Europe".[29] After Poland joined the European Union in 2004, the border controls were relaxed in agreement with the Schengen Agreement to eliminate passport controls by 2007.[30][31] The modern borderlands of Poland and Germany are inhabited by about one million of those countries' citizens within the counties on each side.[26]

See also

- Germany–Poland relations

- General Government

- German partition

- Territorial evolution of Germany

- Territorial evolution of Poland

References

- ^ "WARUNKI NATURALNE I OCHRONA ŚRODOWISKA (ENVIRONMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION)". MAŁY ROCZNIK STATYSTYCZNY POLSKI 2013 (CONCISE STATISTICAL YEARBOOK OF POLAND 2013) (in Polish and English). GŁÓWNY URZĄD STATYSTYCZNY. 2013. p. 26. ISSN 1640-3630.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) (Downloadable pdf file) - ^ Phillip A. Bühler (1990). The Oder-Neisse Line: a reappraisal under international law. East European Monographs. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-88033-174-6.

- ^ a b c d R. F. Leslie (1980). The History of Poland Since 1863. Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9.

- ^ Piotr Wróbel (27 January 2014). Historical Dictionary of Poland 1945-1996. Routledge. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-135-92694-6.

- ^ Wim Blockmans; Peter Hoppenbrouwers (3 February 2014). Introduction to Medieval Europe 300–1500. Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-317-93425-7.

- ^ "Historical Text Archive: Electronic History Resources, online since 1990".

- ^ Knoll, Paul W. (1967). "The stabilization of the Polish Western frontier under Casimir the Great, 1333-1370". The Polish Review. 12 (4): 3–29. JSTOR 25776735.

- ^ a b Norman Davies (31 May 2001). Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-19-164713-0.

- ^ a b Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 419–421. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ a b Yohanan Cohen (1 February 2012). Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation. SUNY Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7914-9938-2.

- ^ Nicholas A. Robins; Adam Jones (2009). Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice. Indiana University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6.

- ^ Eastern Europe. ABC-CLIO. 2005. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- ^ Manfred F. Boemeke; Gerald D. Feldman; Elisabeth Gläser (13 September 1998). The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment After 75 Years. Cambridge University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-521-62132-8.

- ^ Richard Felix Staar. Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe: Fourth Edition. Hoover Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-8179-7693-4.

- ^ a b John E. Jessup (1 January 1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945-1996. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 543. ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9.

- ^ a b Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 398–399. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ Reuben Wong; Christopher Hill (27 April 2012). National and European Foreign Policies: Towards Europeanization. Taylor & Francis. p. 323. ISBN 978-1-136-71925-7.

- ^ "Historia linii Curzona: Jak Stalin został obrońcą sprawy polskiej?". FOCUS.pl. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Lynn Tesser (14 May 2013). Ethnic Cleansing and the European Union: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Security, Memory and Ethnography. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-137-30877-1.

- ^ Kimmo Katajala; Maria Lähteenmäki (2012). Imagined, Negotiated, Remembered: Constructing European Borders and Borderlands. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 204. ISBN 978-3-643-90257-3.

- ^ "Oznakowanie granic 1945-1990".

- ^ Britannica Educational Publishing (1 June 2013). Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. Britanncia Educational Publishing. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-61530-991-7.

- ^ Joseph A. Biesinger (1 January 2006). Germany: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Infobase Publishing. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-8160-7471-6.

- ^ Paul B. Stares (1992). The New Germany and the New Europe. Brookings Institution Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8157-2099-8.

- ^ a b Godfrey Baldacchino (21 February 2013). The Political Economy of Divided Islands: Unified Geographies, Multiple Polities. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-1-137-02313-1.

- ^ a b Paul Ganster (1 January 1997). Borders and Border Regions in Europe and North America. SCERP and IRSC publications. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-925613-23-3.

- ^ Sven Tägil (1 January 1999). Regions in Central Europe: The Legacy of History. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-85065-552-7.

- ^ Paulina Bren; Mary Neuburger (8 August 2012). Communism Unwrapped: Consumption in Cold War Eastern Europe. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 377–385. ISBN 978-0-19-982766-4.

- ^ Torin Monahan (2006). Surveillance and Security: Technological Politics and Power in Everyday Life. Taylor & Francis. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-415-95393-1.

- ^ Fred M. Shelley (23 April 2013). Nation Shapes: The Story Behind the World's Borders. ABC-CLIO. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-1-61069-106-2.

- ^ http://www.presseurop.eu/en/content/article/234841-schengen-real-europe [dead link]

Further reading

- Bjork, Jim (2014). "Church Fights: Nationality, Class, and the Politics of Church-Building in a German-Polish Borderland, 1890–1914". Borderlands in World History, 1700–1914. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 192–213. ISBN 978-1-137-32058-2.

External links