Illustrious Corpses

| Illustrious Corpses (Cadaveri eccellenti) | |

|---|---|

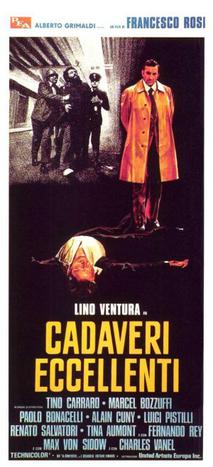

Italian film poster | |

| Directed by | Francesco Rosi |

| Written by | Tonino Guerra Lino Jannuzzi Francesco Rosi Leonardo Sciascia |

| Produced by | Alberto Grimaldi |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Pasqualino De Santis |

| Edited by | Ruggero Mastroianni |

| Music by | Piero Piccioni |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | United Artists Europa |

Release date |

|

Running time | 127 minutes |

| Countries | Italy France |

| Language | Italian |

Illustrious Corpses (Italian: Cadaveri eccellenti) is a 1976 Italian-French thriller film directed by Francesco Rosi and starring Lino Ventura, based on the novel Equal Danger by Leonardo Sciascia (1971).[1] The film was screened at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival, but was not entered into the main competition.[2]

Its title refers to the surrealist game, Cadavre Exquis, invented by André Breton, in which the participants draw consecutive sections of a figure without seeing what the previous person has drawn, leading to unpredictable results, and is meant to describe the meandering nature of the film with its unpredictable foray into the world of political manipulations, as well as the ("illustrous") corpses of the murdered judges.

In 2008, the film was selected to enter the list of the 100 Italian films to be saved.[3][4][5]

Plot

The film starts with the murder of Investigating Judge Vargas in Palermo, amongst a climate of demonstrations, strikes and political tension between the Left and the Christian Democratic government. The subsequent investigation failing, the police assign Inspector Rogas (Lino Ventura), a man with a firm faith in the integrity of the judiciary, to solve the case. While he is starting his investigation, two judges are killed. All victims turn out to have worked together on several cases. After Rogas discovers evidence of corruption surrounding the three government officials, he is encouraged by superiors "not to forage after gossip," but to trail the "crazy lunatic who for no reason whatever is going about murdering judges." This near admission of guilt drives Rogas to seek out three men wrongfully convicted by the murdered judges. He is joined by a journalist friend working for a far-left newspaper, Cusan.

Rogas finds his likely suspect in Cres, a man who was convicted of attempting to kill his wife. Mrs. Cres accused her husband of trying to kill her by poisoning her rice pudding, which she escaped only because she fed a small portion first to her cat, who died. Rogas concludes that he was probably framed by his wife, and seeks him out, only to find that he has disappeared from his house. Meanwhile another investigating judge is killed, and eyewitnesses see two young revolutionaries running away from the scene. Rogas, close to finding his man, is demoted, and told to work with the political division to pin the crimes on the revolutionary Leftist terrorist groups.

Rogas discovers that his phone is tapped. He seeks out the Supreme Court's president (Max von Sydow) in order to warn him that he is most likely the next victim. The president details a philosophy of justice wherein the court is incapable of error by definition. Music from a party in the same building leads to Rogas discovering the Minister of Justice (Fernando Rey) at the party with many revolutionary leaders, amongst them the editor of the revolutionary paper Cusan is working for, Galano, and Mrs. Cres. He and the Minister have a discussion, where the Minister reveals that sooner or later, his party will have to form a coalition with the Communist Party, and that it will be their task to prosecute the far-leftist groups. The murder of the judges as well as Rogas's investigations help raise the tension and justify the prosecution of the far-left groups. Rogas also discovers that his suspect, Cres, is present at the party. Rogas meets with the Secretary-General of the Communist Party in a museum. Both of them are killed. Amongst rising tensions between revolutionaries and the government, which mobilizes the army, the murder of the Secretary-General is blamed on Rogas by the chief of police. The film ends with a discussion between Cusan and the vice-secretary of the Communist Party, who claims that the time is not yet ready for the revolution and the party will not react to the government's actions. "But then the people must never know the truth?", asks Cusan. The vice-secretary answers: "The truth is not always revolutionary." It is a sardonic concluding comment on the strategy at the time of the 'historic compromise' with Christian Democracy adopted by the Communist party, referring back to the motto 'To tell the truth is revolutionary' adopted from Ferdinand Lassalle by Antonio Gramsci, the party's most famous former leader and author of the Prison Notebooks.

Cast

- Lino Ventura as Inspector Amerigo Rogas

- Tino Carraro as Chief of Police

- Marcel Bozzuffi as The lazy

- Paolo Bonacelli as Dr. Maxia

- Alain Cuny as Judge Rasto

- Maria Carta as Madame Cres

- Luigi Pistilli as Cusan

- Tina Aumont as The prostitute

- Renato Salvatori as Police Commissary

- Paolo Graziosi as Galano

- Anna Proclemer as Nocio's wife

- Fernando Rey as Security Minister

- Max von Sydow as Supreme Court president

- Charles Vanel as Varga

Release

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2019) |

Critical response

The film triggered a lot of controversy at its release, especially for the joke pronounced in the last part of the film by the communist party secretary "Truth is not always revolutionary", which is used by Rosi to denote the silence of the opposition to the prevailing and much often unpunished corruption.[6]

Illustrious Corpses was presented, out of competition, at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival. The same year, it received the David di Donatello for Best Film, at the same time as Francesco Rosi was awarded the David di Donatello for Best Director.[citation needed]

See also

- Equal Danger, the novel by Leonardo Sciascia on which this film is based.

- List of Italian films of 1976

References

- ^ Canby, Vincent (2011). "New York Times: Illustrious Corpses". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Baseline & All Movie Guide. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Illustrious Corpses". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Massimo Bertarelli, Il cinema italiano in 100 film: i 100 film da salvare, Gremese Editore, 2004, ISBN 88-8440-340-5.

- ^ Massimo Borriello (4 March 2008). "Cento film e un'Italia da non dimenticare". Movieplayer. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare". Corriere della Sera. 28 February 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Pellicole da riscoprire: Cadaveri eccellenti, di Francesco Rosi". 14 October 2014. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

External links

- 1976 films

- 1970s psychological thriller films

- 1970s Italian-language films

- Italian political thriller films

- Police detective films

- 1970s political thriller films

- Films directed by Francesco Rosi

- Films based on works by Leonardo Sciascia

- Films about the Sicilian Mafia

- Films set in Rome

- United Artists films

- Films based on Italian novels

- Films with screenplays by Tonino Guerra

- Films produced by Alberto Grimaldi

- Films scored by Piero Piccioni

- 1970s Italian films