Lewis Stone

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

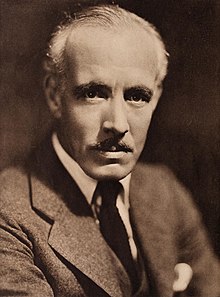

Lewis Stone | |

|---|---|

Portrait in Photoplay, 1923 | |

| Born | Lewis Shepard Stone November 15, 1879 Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 12, 1953 (aged 73)[1] Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1911–1953 |

| Employer | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1924–1953)[1] |

| Spouse(s) |

Margaret Langham (stage name)

(m. 1906; died 1917)Hazel Elizabeth Woof (m. 1930; his death) |

| Children | 3[2] |

Lewis Shepard Stone (November 15, 1879 – September 12, 1953) was an American film actor. He spent 29 years as a contract player at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was best known for his portrayal of Judge James Hardy in the studio's popular Andy Hardy film series.[1] He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1929 for his performance as Russian Count Pahlen in The Patriot. Stone was also cast in seven films with Greta Garbo, including in the role of Doctor Otternschlag in the 1932 drama Grand Hotel.

Early life

[edit]

Stone was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1879, was youngest of four children of Philena (née Ball) and Bertrand Stone.[5] His father, according to the federal census of 1880, supported the family as a boot cutter.[5] After obtaining his public education in Worcester, Lewis joined the United States Army during the Spanish–American War, serving as a lieutenant and later being deployed to China to train troops.[1] He returned to the United States, and following his discharge from the army began his career as a writer and actor.

Career

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

In the early-1900s Stone was considered by the critics to be the most popular leading man in stock in America. For eight years, he held the role as leading man with the Oliver Morosco Stock Company in Los Angeles.[6]

In 1912, Stone found success in the popular play Bird of Paradise, which starred Laurette Taylor. The play was later filmed in 1932 and 1951.

For the summer of 1913 Stone appeared at Elitch Theatre in Denver, Colorado, as the leading man for the season. The proprietor of the theatre, Mary Elitch Long, recalled an event when Stone heard of a nearby family in need and he "went to a neighborhood grocery and, placing $25.00 on the counter, told the storekeeper to see to it that the bereaved little family wanted for nothing; and to let him know when more money was needed and to say nothing about it."[6]

His career was interrupted by a return to the Army in World War I, serving as a major in the cavalry.[1]

Before leaving for the war he made his feature film debut in Honor's Altar in 1916.[1] He showed up in First National's 1920 Nomads of the North to good effect playing a Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman. He portrayed the title role in the 1922 silent film version of The Prisoner of Zenda.

From 1920 to 1927, he lived in Los Angeles at 212 S. Wilton Place. The home is now Los Angeles Cultural-Historic Monument #925 and is in the Wilton Historic District.[7]

In 1924, he joined newly formed Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio and was contracted by it up until his death.[1]

Stone was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1929 for The Patriot. He played the character that gives the film its title, but he was not the top-billed star. He appeared in seven films with Greta Garbo, spanning both the silent and early sound periods. He played the role of Dr. Otternschlag in the Garbo film Grand Hotel, in which he utters the famous closing line "Grand Hotel. People coming. Going. Nothing ever happens."

He played a larger role in the 1933 Garbo film Queen Christina. His appearance in the successful prison film The Big House furthered his career. He played adventurers in the dinosaur epic The Lost World (1925) with Wallace Beery and The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) with Boris Karloff, and a police captain in Bureau of Missing Persons (1933).

In 1937, Stone got the role which became his most famous, that of honest and kind-hearted Judge James Hardy in the Andy Hardy film series, starring Mickey Rooney.[1] Stone appeared as the judge in 14 of the 16 Hardy movies, beginning with You're Only Young Once (1937). Lionel Barrymore had played the judge in the first Hardy movie, and Stone died before the making of the last one, Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958), so the judge's own death was mentioned in the film. During the heyday of the series, Stone also appeared with Rooney in the short subject Andy Hardy's Dilemma, which promoted charitable donations to the Community Chest.

During World War II, the 60-plus year-old Stone was a lieutenant colonel in the California National Guard.[1]

Stone was MGM's longest-contracted actor and the longest-ever-contracted actor at a studio up to his death.[1] The week before his death, he (together with Lionel Barrymore) received a gold key to his dressing room. He made approximately 100 movies.[1]

Personal life

[edit]Stone owned a beach house in the Venice neighborhood of Los Angeles. In 1930 the oil drilling boom in the Venice Beach-Del Ray oil field caused him to file a lawsuit to stop the beach lease in order to prevent property damage and public nuisance. "The court ruled for Stone even though derricks ringed the beach ..."[8]

In the 1930s he owned a 104-foot luxury yacht named Serena. In 1937 the yacht was sold to Robert Paine Scripps (the father of Charles Scripps) and converted to a research vessel named the E. W. Scripps.[9]

Stone campaigned for the reelection of President Herbert Hoover in 1932.[10]

Death

[edit]Stone died in Hancock Park, Los Angeles on September 12, 1953, aged 73.[1] He reportedly suffered a heart attack while chasing away some neighborhood kids[1] who were throwing rocks at his garage or trampling his meticulously kept prized garden. Another published report states that on that date Stone and his third wife were watching television when they heard a racket in the back yard. When he investigated, Stone found lawn furniture once again floating in the pool and glimpsed three or perhaps four teenage boys running toward the street. Stone gave chase despite his wife's warning not to exert himself. Upon reaching the sidewalk, Stone suddenly collapsed. A gardener, Juan Vergara, witnessed the chase and summoned aid.

A photo published in newspapers of the day showed Stone lying on the sidewalk immediately after the incident. The photo was later included in Kenneth Anger's book of scandals titled Hollywood Babylon.

Lewis Stone was later honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6524 Hollywood Blvd.

Selected filmography

[edit]- The Bargain (1914)

- Honor's Altar (1916) as Warren Woods

- The Havoc (1916) (with Gladys Hanson) as Richard Craig

- According to the Code (1916) as Basil Beckenridge

- Inside the Lines (1918) as Captain Cavendish

- The Man of Bronze (1918) as John Adams

- Man's Desire (1919) as Tom Denton

- Milestones (1920) as John Rhead

- Nomads of the North (1920) as Cpl. O'Connor

- Held by the Enemy (1920) as Capt. Gordon Haine

- The Concert (1921) as Augustus Martinot

- Beau Revel (1921) as Lawrence 'Beau' Revel

- The Golden Snare (1921) as Sergeant Philip Raine

- Don't Neglect Your Wife (1921) as Langdon Masters

- The Child Thou Gavest Me (1921) as Edward Berkeley

- Pilgrims of the Night (1921) as Philip Champion / Lord Ellingham

- The Rosary (1922) as Father Brian Kelly

- A Fool There Was (1922) as John Schuyler

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1922) as Rudolf Rassendyll / King Rudolf

- Trifling Women (1922) as The Marquis Ferroni

- The Dangerous Age (1923) as John Emerson

- The World's Applause (1923) as John Elliott

- You Can't Fool Your Wife (1923) as Garth McBride

- Scaramouche (1923) as The Marquis de la Tour d'Azyr

- The Stranger (1924) as Keith Darrant

- Why Men Leave Home (1924) as John Emerson

- Cytherea (1924) as Lee Randon

- Husbands and Lovers (1924) as James Livingston

- Inez from Hollywood (1924) as Stewart Cuyler

- Cheaper to Marry (1925) as Jim Knight

- The Lost World (1925) as Sir John Roxton

- Confessions of a Queen (1925) as The King

- The Talker (1925) as Harry Lennox

- The Lady Who Lied (1925) as Horace Pierpont

- Fine Clothes (1925) as Earl of Denham

- What Fools Men (1925) as Joseph Greer

- Too Much Money (1926) as Robert Broadley

- The Girl from Montmartre (1926) asJerome Hautrive

- Old Loves and New (1926) as Gervas Carew

- Don Juan's Three Nights (1926) as Johann Aradi

- Midnight Lovers (1926) as Maj. William Ridgewell, RFC

- The Blonde Saint (1926) as Sebastian Maure

- An Affair of the Follies (1927) as Hammersley

- The Notorious Lady (1927) as Patrick Marlowe / John Carew

- Lonesome Ladies (1927) as John Fosdick

- The Prince of Headwaiters (1927) as Pierre

- The Private Life of Helen of Troy (1927) as Menelaus

- The Foreign Legion (1928) as Col. Destin

- The Patriot (1928) as Count Pahlen

- Freedom of the Press (1928) as Daniel Steele

- A Woman of Affairs (1928) as Dr. Hugh Trevelyan

- Wild Orchids (1929) as John Sterling

- The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929) as Edward West

- Wonder of Women (1929) as Stephen Trombolt

- Madame X (1929) as Louis Floriot

- Their Own Desire (1929) as Marlett

- Strictly Unconventional (1930) as Clive Champion-Cheney

- The Big House (1930) as Warden James Adams

- Romance (1930) as Cornelius Van Tuyl

- The Office Wife (1930) as Lawrence Fellowes

- Passion Flower (1930) as Antonio Morado

- Inspiration (1931) as Raymond Delval

- Father's Son (1931) as William Emory

- The Secret Six (1931) as Richard Newton, Attorney at Law

- My Past (1931) as Mr. John Thornley

- Always Goodbye (1931) as John Graham

- The Bargain (1931) as Maitland White

- The Phantom of Paris (1931) as Detective Costaud

- The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931) as Carlo Boretti

- Mata Hari (1931) as Andriani

- Strictly Dishonorable (1931) as The Judge

- The Wet Parade (1932) as Roger Chilcote

- Grand Hotel (1932) as Dr. Otternschlag

- Night Court (1932) as Judge William Osgood

- Letty Lynton (1932) as District Attorney Haney

- New Morals for Old (1932) as Mr. Thomas

- Red-Headed Woman (1932) as William Legendre Sr.

- Unashamed (1932) as Henry Trask

- Divorce in the Family (1932) as John Parker

- The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) as Nayland Smith

- The Son-Daughter (1932) as Dr. Dong Tong

- Men Must Fight (1933) as Edward Seward

- The White Sister (1933) as Prince Guido Chiaromonte

- Looking Forward (1933) as Gabriel Service Sr.

- Bureau of Missing Persons (1933) as Capt. Webb

- Queen Christina (1933) as Axel Oxenstierna

- You Can't Buy Everything (1934) as John Burton

- The Mystery of Mr. X (1934) as Inspector Connor

- The Girl from Missouri (1934) as Frank Cousins

- Treasure Island (1934) as Captain Smollett

- David Copperfield (1935) as Mr. Wickfield

- Vanessa: Her Love Story (1935) as Adam Paris

- West Point of the Air (1935) as General Carter

- Public Hero No. 1 (1935) as Prison Warden

- Woman Wanted (1935) as District Attorney Martin

- China Seas (1935) as Tom Davids

- Shipmates Forever (1935) as Adm. Richard Melville

- Tough Guy (1936) as Davis (scenes deleted)

- Three Godfathers (1936) as James Underwood, aka Doc

- The Unguarded Hour (1936) as General Lawrence

- Small Town Girl (1936) as Doctor Dakin

- Suzy (1936) as Baron Charville

- Sworn Enemy (1936) as Doctor Simon 'Doc' Gattle

- Don't Turn 'Em Loose (1936) as John Webster

- Outcast (1937) as Anthony Abbott (lawyer)

- The Thirteenth Chair (1937) as Inspector Marney

- The Man Who Cried Wolf (1937) as Lawrence Fontaine

- You're Only Young Once (1937) as Judge James K. Hardy

- The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937) as Mr. Jackson Douglas

- Judge Hardy's Children (1938) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Stolen Heaven (1938) as Joseph Langauer

- Yellow Jack (1938) as Major Reed

- Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938) as Judge James K. Hardy

- The Chaser (1938) as Dr. Delford Q. Prescott

- Out West with the Hardys (1938) as Judge James 'Jim' K. Hardy

- The Ice Follies of 1939 (1939) as Douglas Tolliver Jr.

- The Hardys Ride High (1939) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Joe and Ethel Turp Call on the President (1939) as The President

- Judge Hardy and Son (1939) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Andy Hardy Meets Debutante (1940) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Sporting Blood (1940) as Davis Lockwood

- Andy Hardy's Dilemma: A Lesson in Mathematics... and Other Things (1940, short) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Andy Hardy's Private Secretary (1941) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Life Begins for Andy Hardy (1941) as Judge James K. Hardy

- The Bugle Sounds (1942) as Col. Jack Lawton

- The Courtship of Andy Hardy (1942) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Andy Hardy's Double Life (1942) as Judge James K. Hardy

- Plan for Destruction (1943, short) as Himself – Commentator

- Andy Hardy's Blonde Trouble (1944) as Judge James K. Hardy

- The Hoodlum Saint (1946) as Father Nolan

- Three Wise Fools (1946) as Judge James Trumbell

- Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946) as Judge James K. Hardy

- State of the Union (1948) as Sam Thorndyke

- The Sun Comes Up (1949) as Arthur Norton

- Any Number Can Play (1949) as Ben Gavery Snelerr

- Key to the City (1950) as Judge Silas Standish

- Stars in My Crown (1950) as Dr. Daniel Kalbert Harris, Sr.

- Grounds for Marriage (1951) as Dr. Carleton Radwin Young

- Night Into Morning (1951) as Dr. Horace Snyder

- Angels in the Outfield (1951) as Commissioner Arnold P. Hapgood

- Bannerline (1951) as Josh

- The Unknown Man (1951) as Judge James V. Hulbrook

- It's a Big Country (1951) as Church Sexton

- Just This Once (1952) as Judge Samuel Coulter

- Talk About a Stranger (1952) as Mr. Wardlaw

- Scaramouche (1952) as Georges de Valmorin

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1952) as The Cardinal

- All the Brothers Were Valiant (1953) as Capt. Holt

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Obituaries". Variety. September 16, 1953. p. 63. Retrieved October 4, 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b "Drop from Eighth Story Window Kills Mrs. Lewis Stone". Los Angeles Herald. Vol. XLII, no. 186. June 6, 1917. p. 5.

- ^ According to the database California County Marriages 1850-1952, Lewis S. Stone married Margaret H. Huddleston (real name of Margaret Langham) in Los Angeles on Sunday, December 30, 1906. The marriage was not officially registered with Los Angeles County until 1907.

- ^ "Florence Oakley". IMDb.

- ^ a b "United States Census, 1880", digital image of original census page documenting Lewis Stone in household of Bertrand Stone, Worcester, Worcester County, Massachusetts; enumeration district (ED) 903, sheet 608D; National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C. FamilySearch database with images, Salt Lake City Utah.

- ^ a b Borrillo, Theodore A. (2012). Denver's historic Elitch Theatre : a nostalgic journey (a history of its times). [publisher not identified]. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-9744331-4-1. OCLC 823177622.

- ^ "Historic–Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: City Declared Monuments". Los Angeles City Planning. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2018.

- ^ Elkind, Sarah S. (2012). "Oil in the City: The Fall and Rise of Oil Drilling in Los Angeles". Journal of American History. 99: 82–90. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas079.

- ^ Nelson, Stewart B. (1971). Oceanographic Ships, Fore and Aft. Washington, DC: Office of the Oceanographer of the Navy, U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 105.

- ^ "Editorial". The Napa Daily Register. November 2, 1932. p. 6.

External links

[edit]- Lewis Stone at IMDb

- Lewis Stone at the Internet Broadway Database

- Lewis Stone at The New York Times Movies

- Lewis Stone at The International Silent Movie

- Photographs of Lewis Stone

- 1879 births

- 1953 deaths

- Military personnel from Massachusetts

- United States Army Cavalry Branch personnel

- Male actors from Worcester, Massachusetts

- People from Hancock Park, Los Angeles

- American male film actors

- American male silent film actors

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract players

- 20th-century American male actors

- Burials at Kensico Cemetery

- American military personnel of the Spanish–American War

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army officers