Mastodon: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 204.186.102.241 to version by RockMagnetist. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1306809) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

''M. raki'': Endemic to North America from the Pliocene, living from 4.9–1.8 mya, existing for about 3.1 million years.<ref>[http://paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?action=checkTaxonInfo&taxon_no=47872&is_real_user=1 PaleoBiology Database: ''Mammut raki'', basic info]</ref> The evidence for this species was first discovered in [[New Mexico]], "from beds bearing teeth of Pleistocene ''Equus'' and elsewhere". The name was once regarded as a subjective synonym of ''[[Mammut americanum]]'', before being tentatively placed under this name. The latter species, the American Mastodon, is recorded at only four beds, dated to the later [[Pleistocene]], in New Mexico.<ref> Lucas, Spencer G., Morgan, Gary S. 1997. The American Mastodont (''Mammut americanum'') in New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, '''42'''(3):312-317</ref> Other ''Mammut'' are rarely found from the [[Blancan]] period, and only in fossil beds of northern regions, ''Mammut raki'' is the earliest example of the genus to have been discovered in the region.<ref name ="Lucas"/> The species was first described by [[Childs Frick]] in 1933 as '''''Mastodon raki''''', assigning it to the genus ''Mastodon'' ([[Georges Cuvier|Cuvier]]). The [[Type locality (biology)|type locality]] was originally indicated as "Hot Springs, New Mexico". The specific epithet commemorates the collector Joseph Rak, who provided the specimen to the [[American Museum of Natural History]]. This [[mandible]] is retained in the museum's (AMNH) collection as F:AM2335, the prefix designating it as part of Frick's collection.<ref name ="Lucas"/> The name was recombined as ''Mammut raki'' by Tedford in 1981, the generic epithet ''Mammut'' having priority over Cuvier's later description.<ref>PaleoBiology citing R. H. Tedford. 1981. Geological Society America Bulletin 92</ref> In 1999 the authors Lucas and Morgan discerned the type to have been obtained by Rak at a site seven miles north of Hot Springs, later named [[Truth or Consequences, New Mexico|Truth or Consequences]], to the west of [[Elephant Butte Reservoir]] in the Palomos Formation. Lucas and Morgan redescribed the specimen F:AM2335, provided photographs and an illustration, and attributed a provenance to this [[holotype]]. The distinguishing characteristics of the teeth present in mandible was found to be similar to the description of ''Pliomastodon'' and supported its current arrangement as an early species of ''Mammut''.<ref name ="Lucas">S. G. Lucas and G. S. Morgan. 1999. "The oldest ''Mammut'' (Proboscidea; Mammalia) from New Mexico". New Mexico Geology 21</ref> The mammalian fauna found alongside ''Mammut raki'' include ''[[Equus simplicidens]]'' and ''[[Gigantocamelus]]''. The age of the holotype was inferred from the morphology of the mandible and teeth, and by the [[biochronology]] of the nearby mammalian assemblage.<ref name ="Lucas"/> |

''M. raki'': Endemic to North America from the Pliocene, living from 4.9–1.8 mya, existing for about 3.1 million years.<ref>[http://paleodb.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?action=checkTaxonInfo&taxon_no=47872&is_real_user=1 PaleoBiology Database: ''Mammut raki'', basic info]</ref> The evidence for this species was first discovered in [[New Mexico]], "from beds bearing teeth of Pleistocene ''Equus'' and elsewhere". The name was once regarded as a subjective synonym of ''[[Mammut americanum]]'', before being tentatively placed under this name. The latter species, the American Mastodon, is recorded at only four beds, dated to the later [[Pleistocene]], in New Mexico.<ref> Lucas, Spencer G., Morgan, Gary S. 1997. The American Mastodont (''Mammut americanum'') in New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, '''42'''(3):312-317</ref> Other ''Mammut'' are rarely found from the [[Blancan]] period, and only in fossil beds of northern regions, ''Mammut raki'' is the earliest example of the genus to have been discovered in the region.<ref name ="Lucas"/> The species was first described by [[Childs Frick]] in 1933 as '''''Mastodon raki''''', assigning it to the genus ''Mastodon'' ([[Georges Cuvier|Cuvier]]). The [[Type locality (biology)|type locality]] was originally indicated as "Hot Springs, New Mexico". The specific epithet commemorates the collector Joseph Rak, who provided the specimen to the [[American Museum of Natural History]]. This [[mandible]] is retained in the museum's (AMNH) collection as F:AM2335, the prefix designating it as part of Frick's collection.<ref name ="Lucas"/> The name was recombined as ''Mammut raki'' by Tedford in 1981, the generic epithet ''Mammut'' having priority over Cuvier's later description.<ref>PaleoBiology citing R. H. Tedford. 1981. Geological Society America Bulletin 92</ref> In 1999 the authors Lucas and Morgan discerned the type to have been obtained by Rak at a site seven miles north of Hot Springs, later named [[Truth or Consequences, New Mexico|Truth or Consequences]], to the west of [[Elephant Butte Reservoir]] in the Palomos Formation. Lucas and Morgan redescribed the specimen F:AM2335, provided photographs and an illustration, and attributed a provenance to this [[holotype]]. The distinguishing characteristics of the teeth present in mandible was found to be similar to the description of ''Pliomastodon'' and supported its current arrangement as an early species of ''Mammut''.<ref name ="Lucas">S. G. Lucas and G. S. Morgan. 1999. "The oldest ''Mammut'' (Proboscidea; Mammalia) from New Mexico". New Mexico Geology 21</ref> The mammalian fauna found alongside ''Mammut raki'' include ''[[Equus simplicidens]]'' and ''[[Gigantocamelus]]''. The age of the holotype was inferred from the morphology of the mandible and teeth, and by the [[biochronology]] of the nearby mammalian assemblage.<ref name ="Lucas"/> |

||

the fat cat jumed over the moon |

|||

==Discovery== |

==Discovery== |

||

Revision as of 17:55, 31 October 2012

| Mastodon Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted M. americanum skeleton, Museum of the Earth | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | †Mammutidae |

| Genus: | †Mammut Blumenbach, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| †Mammut americanum Kerr, 1792 (originally Elephas)

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

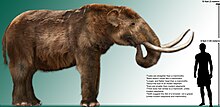

Mastodons (Greek: μαστός "breast" and ὀδούς, "tooth")[1][2] were large, proboscidean mammal species of the extinct genus Mammut that inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of the Pleistocene 11,000 years ago.[3] The American mastodon is the most recent and best-known species of the genus.

Description

While mastodons had a size and appearance similar to elephants and mammoths, they were not particularly closely related. Their teeth differ dramatically from those of members of the elephant family; they had blunt, conical, nipple-like projections on the crowns of their molars,[4] which were more suited to chewing leaves than the high-crowned teeth mammoths used for grazing; the name mastodon (or mastodont) means "nipple teeth" and is also an obsolete name for their genus.[5] Their skulls are larger and flatter than those of mammoths, while their skeleton is stockier and more robust.[6]

Taxonomy and evolution

Mammut is a genus of the extinct family Mammutidae, related to the proboscidean family Elephantidae (mammoths and elephants). The common name "Mastodon" derives from a genus named to describe various extinct members of proboscideans, Mastodon (Cuvier) is not currently used. The assignment of the taxon to Mammut, a name that preceded Cuvier's description, met with resistance and authors sometimes applied "Mastodon" as an informal name.

The ancestors of Mammut diverged from the Elephantidae clade approximately 26.8 million years ago.[7] In 2007 the complete mitochondrial genome of M. americanum was published using an Alaskan fossil tooth dated between 50,000 and 130,000 years old.[8] Working from the previously established date of divergence and utilizing this new sequence as an outgroup to the Elephantidae line, the researchers inferred that the ancestors of the African elephant (Loxodonta sp.) diverged from the line that led to Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) and mammoths approximately 7.6 million years ago, and that the Asian elephant and mammoth lines diverged approximately 6.7 million years ago. This further confirmed another study which, utilizing a fully sequenced wooly mammoth mitochondrial genome showed that the wooly mammoth was more closely related to Asian elephants than African elephants.[9] Furthermore, it demonstrated that M. americanum could be used as an effective outgroup to the Elephantidae clade, representing a preferable alternative to the dugong (Dugong dugon) and hyrax (order Hyracoidea), which had been used previously due to their being the closest living relatives of elephants.

The oldest Mammut fossil (Mammut sp.) was unearthed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The genus gives its name to the family Mammutidae, assigned to the order Proboscidea. They superficially resemble members of the proboscidean family Elephantidae, including mammoths; however, mastodons were browsers, while mammoths were grazers. Confusingly, several genera of proboscids from the gomphothere family have similar-sounding names (e.g., Stegomastodon), but are actually more closely related to elephants than to mastodons.

Species

The American mastodon (Mammut americanum), the most recent member of the genus, lived from about 3.7 million years ago until it became extinct about 10,000 years BCE. It is known from fossils found ranging from present-day Alaska and New England in the north, to Florida, southern California, and as far south as Honduras.[10] The American mastodon resembled a woolly mammoth in appearance, with a thick coat of shaggy hair.[11] It had tusks that sometimes exceeded five meters in length; they curved upwards, but less dramatically than those of the woolly mammoth.[6] Its main habitat was cold spruce woodlands, and it is believed to have browsed in herds.[12] They are generally reported as having disappeared from North America about 12,700 years ago,[13] as part of a mass extinction of most of the Pleistocene megafauna, widely presumed to have been as a result of rapid climate change in North America, as well as the sophistication of stone tool weaponry used by the Clovis hunters.[13] The latest Paleo-Indians entered the American continent and expanded to relatively large numbers 13,000 years ago,[14] and their hunting may have caused a gradual attrition of the mastodon population.[15][16]

M. cosoensis: Originally described from a fossil molar as Pliomastodon cosoensis by Schultz (1937). It was found in the late Pliocene (Blancan) Coso Formation of California. Later recombined as Mammut cosoensis by Shoshani and Tassy (1996).[17][18][19]

M. furlongi: Described by Shotwell and Russell (1963). Its remains where found in the late Miocene (Clarendonian) Jontura Formation of Oregon.[20][21] There's uncertainty in the validity of the species as Lambert and Shoshani (1998) did not recognize it.[22]

M. raki: Endemic to North America from the Pliocene, living from 4.9–1.8 mya, existing for about 3.1 million years.[23] The evidence for this species was first discovered in New Mexico, "from beds bearing teeth of Pleistocene Equus and elsewhere". The name was once regarded as a subjective synonym of Mammut americanum, before being tentatively placed under this name. The latter species, the American Mastodon, is recorded at only four beds, dated to the later Pleistocene, in New Mexico.[24] Other Mammut are rarely found from the Blancan period, and only in fossil beds of northern regions, Mammut raki is the earliest example of the genus to have been discovered in the region.[25] The species was first described by Childs Frick in 1933 as Mastodon raki, assigning it to the genus Mastodon (Cuvier). The type locality was originally indicated as "Hot Springs, New Mexico". The specific epithet commemorates the collector Joseph Rak, who provided the specimen to the American Museum of Natural History. This mandible is retained in the museum's (AMNH) collection as F:AM2335, the prefix designating it as part of Frick's collection.[25] The name was recombined as Mammut raki by Tedford in 1981, the generic epithet Mammut having priority over Cuvier's later description.[26] In 1999 the authors Lucas and Morgan discerned the type to have been obtained by Rak at a site seven miles north of Hot Springs, later named Truth or Consequences, to the west of Elephant Butte Reservoir in the Palomos Formation. Lucas and Morgan redescribed the specimen F:AM2335, provided photographs and an illustration, and attributed a provenance to this holotype. The distinguishing characteristics of the teeth present in mandible was found to be similar to the description of Pliomastodon and supported its current arrangement as an early species of Mammut.[25] The mammalian fauna found alongside Mammut raki include Equus simplicidens and Gigantocamelus. The age of the holotype was inferred from the morphology of the mandible and teeth, and by the biochronology of the nearby mammalian assemblage.[25] the fat cat jumed over the moon

Discovery

Fossils have been found in Africa and North America. In 1900, archaeologist Dr. James K. Hampson documented the discovery of skeletal remains of a mastodon on Island No. 35 of the Mississippi River, Tipton County, Tennessee. The site of the prehistoric find is approximately 3 mi (4,8 km) east of Reverie, Tennessee and 23 mi (37 km) south of Blytheville, Arkansas.[27] During heavy rain in June 1900, sand at the point bar of Island No. 35 had been washed away, exposing the mastodon skeleton in the sediment when the water retreated from the sandbar in July of the same year. John Pendleton, a resident of Island No. 35, notified his neighbor Dr. James K. Hampson about unusual bones he had found exposed by the retreating water at the head of the river island. Reportedly, Hampson visited the site of the find "2 or 3 weeks" after the prehistoric bones had been discovered. By the time of Hampson's arrival, many of the bones had been stolen and the skeleton had been considerably damaged by "curiosity seekers" and "ivory hunters". The remainder of the skeleton ("mainly parts of the hind leg and pelvis") were excavated by Hampson with the help of a pick to separate the mastodon bones from the gravel and pebbles in which they had been resting "cemented together by a clay".[27] Although this find was initially believed to be the remains of a single animal, Morse and Morse[28] subsequently reported that the site consisted of at least two separate mastodons. Several human artifacts were recovered in possible association with the skeletal remains.[27] However, these materials lack direct provenance, and it is generally believed that the artifacts and skeletal remains do not represent Paleoindian/Paleoelephant interaction.[28][29] In 1957 the site was reported as destroyed.[27] The remaining mastodon bones are on display in the Hampson Museum State Park. The Tipton County Museum in Covington also exhibits some fossilized mastodon bones.

Excavations conducted from 1993 through early 2000 at the Diamond Valley Lake reservoir outside of Hemet in Riverside County, California yielded numerous remains of mastodon, as well as numerous other Pleistocene animals. The abundance of these remains, all recovered by paleontologists from the San Bernardino County Museum, led to the site being nicknamed the "Valley of the Mastodons".

Currently, excavations are going on annually at the Hiscock Site in Byron, New York, for mastodon and related Paleo-Indian artifacts. The site was discovered in 1959 by the Hiscock family while digging a pond with a backhoe; they found a large tusk and stopped digging. The Buffalo Museum of Science has organized the dig since 1983. There were also excavations at Montgomery, New York in the late 1990s.

In August 2009, workers in Indiana, while digging a coal-slurry storage pit, unearthed mastodon remains. These remains include pieces of ribs, skull, tusks, and a kneecap; they were turned over to the Indiana State Museum for study and preservation.[30]

See also

References

- ^ mastodon Online Etymology Dictionary Retrieved 30 June 2012

- ^ mastodon Merriam-Webster Retrieved 30 June 2012

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Mammut, basic info

- ^ Mastodons

- ^ Agusti, Jordi and Mauricio Anton (2002). Mammoths, Sabretooths, and Hominids. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-231-11640-3.

- ^ a b Kurtén and Anderson, p. 345

- ^ Shoshani, Jeheskel, et al. 2006. A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a ‘‘missing link’’ between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Vol. 103. 17296–17301.

- ^ Rohland, Nadin, et al. 2007. Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology And Mode Of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon As Outgroup. Plos Biology 5.8. 1663-1671.

- ^ Krause, J. et al. 2006. Multiplex amplification of the mammoth mitochondrial genome and the evolution of Elephantidae. Nature. 439 (7077). 724–727.

- ^ Polaco, O. J.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Corona-M., E.; López-Oliva, J. G. (2001). "The American Mastodon Mammut americanum in Mexico" (PDF). In Cavarretta, G.; Gioia, P.; Mussi, M.; Palombo, M. R. (eds.). The World of Elephants - Proceedings of the 1st International Congress, Rome October 16–20, 2001. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. pp. 237–242. ISBN 88-8080-025-6. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 124. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 243. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ a b "Old American theory is 'speared'". BBC News. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ^ Beck, Roger B. (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Ward, Peter (1997). The Call of Distant Mammoths. Springer. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-387-98572-5.

- ^ Fisher, Daniel C. (2009). "Paleobiology and Extinction of Proboscideans in the Great Lakes Region of North America" (PDF). In Haynes, Gary (ed.). American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 55–75. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Mammut cosoensis, basic info

- ^ J. R. Schultz. 1937. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 487

- ^ J. Shoshani and P. Tassy. 1996. Summary, conclusions, and a glimpse into the future. in J. Shoshani and P. Tassy, eds., The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives, 335–348

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Mammut furlongi, basic info

- ^ J. A. Shotwell and D. E. Russell. 1963. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 53

- ^ Retallack, Gregory J. (2004). "Late Miocene climate and life on land in Oregon within a context of Neogene global change" (PDF). Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ PaleoBiology Database: Mammut raki, basic info

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G., Morgan, Gary S. 1997. The American Mastodont (Mammut americanum) in New Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 42(3):312-317

- ^ a b c d S. G. Lucas and G. S. Morgan. 1999. "The oldest Mammut (Proboscidea; Mammalia) from New Mexico". New Mexico Geology 21

- ^ PaleoBiology citing R. H. Tedford. 1981. Geological Society America Bulletin 92

- ^ a b c d Williams, Stephen (Apr., 1957). "The Island 35 Mastodon: Its Bearing on the Age of Archaic Cultures in the East". American Antiquity. 22 (4): 359–372. doi:10.2307/276134.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ a b Morse, Dan F.; Morse, Phyllis A. (1983), "Paleo-indian Beginnings (9500-8500)", in Morse, Dan F.; Morse (eds.), Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley, New York: Academic Press, pp. 50–69

{{citation}}:|editor-first3=missing|editor-last3=(help) - ^ Corgan, James X. and Emanuel Breitburg (1996): "Tennessee’s Prehistoric Vertebrates." State of Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Geology Bulletin 84, Nashville.

- ^ "NEW: Mastodon remains found 30 miles south of Terre Haute". TribStar.com. 18 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

External links

- The Rochester Museum of Science - Expedition Earth Glaciers & Giants

- Illinois State Museum - Mastodon

- Calvin College Mastodon Page

- American Museum of Natural History - Warren Mastodon

- BBC Science and Nature:Animals - American mastodon Mammut americanum

- BBC News - Greek mastodon find 'spectacular'

- Paleontological Research Institute - The Mastodon Project

- Missouri State Parks and Histroric Sites - Mastodon State Historic Site

- Saint Louis Front Page - Mastodon State Historic Site

- The Florida Museum of Natural History Virtual Exhibit - The Aucilla River Prehistory Project:When The First Floridians Met The Last Mastodons

- Worlds longest tusks

- Western Center for Archaeology & Paleontology, home of the largest mastodon ever found in the Western United States

- Smithsonian Magazine Features Mammoths and Mastodons

- 360 View of Mastodon Skull from Indiana State Museum