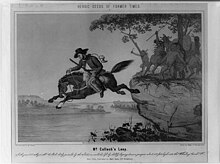

McColloch's Leap

McColloch's Leap was a feat performed during a September 1777 attack by Native Americans on Fort Henry, site of present-day Wheeling, West Virginia, during the American Revolutionary War. While escaping a Native American warband, American frontiersman Samuel McColloch rode his horse down a dangerously high and steep drop. Both he and his horse survived without injury. The leap is based on a historic event, but retellings have exaggerated the story into a local legend or tall tale.

Prelude[edit]

Native alliance with British forces[edit]

The Native American forces in this battle were from various tribes, primarily Wyandot and Mingo, with minor contingents from Shawnee and Lenape (Delaware) tribes. They were led by a tribal leader called Half-King Dunquat of the Wyandot people.[1]

The Wyandot were part of the Huron Confederacy which had allied with the British in the Huron–British Treaty of 1760. In the treaty the British recognized the sovereign rights of the native nation, promised an end to British incursions on their lands, and allowed free trade between the two nations in exchange for support for the British during the French and Indian War.[2]

McColloch and the American Militia[edit]

On January 6, 1777, Samuel McColloch was appointed as a major in the Ohio County milita and was given command over Fort Van Meter near Short Creek, West Virginia. There are no records of his military service or qualifications prior to 1777.[3]

On January 28, Major McColloch represented his milita at the Catfish Camp council of war to discuss the ongoing conflict with the Native Americans and to organize communal defense between the various forts and militas in the region.[3] By that summer, rumors of an attack were widespread among the frontiers of Virginia and Pennsylvania. Fort Henry became a focal point of activity in early August, 1777 when the region's commander, General Edward Hand, called over 250 militia men to the fort. Major McColloch and his milita were not among these, presumably because they lived close enough to respond quickly without straining the fort's already meager supplies.[4]

Minor skirmishes took place on August 2 and 4 resulting in two wounded enslaved men and one killed Native. However, after several weeks with no activity, the majority of militia had returned home. This left the fort garrisoned with the companies of Captains Joseph Ogle and Samuel Mason each with about 25 men, and an additional 40 men from the local community.[4]

The Leap[edit]

On September 1, 1777, shortly after watching the majority of militiamen leave for home, a force of 200-300 Native Americans under Half-King Dunquat besieged Fort Henry.[3][5] The fort sent out calls for help throughout the region. Captain Van Swearingen was the first to respond with fourteen men from Cross Creek, about 20 miles north, and was able to enter the fort without issue.[6]

Major McColloch, located about 10 miles north in Short Creek, took the time to gather a larger force of 40 mounted men. By this time, the Native forces were prepared to prevent additional aid from reaching the fort. On seeing McColloch's relief party, the Natives attacked. The fort's defenders saw the attack and sallied out to help McColloch's company reach the fort. McColloch acted as the group's rearguard, fighting back the Native's advances until all of his men were safely inside. However, during the fight, the Native forces cut him off from the fort, and McColloch was forced to flee on his horse to nearby Wheeling Hill with the Natives in close pursuit. Reaching the top of the hill, he found that several groups of Natives had cut off all directions of retreat with the exception of the cliff face above Wheeling Creek.[3] Finding himself surrounded, and unwilling to submit to capture or death at the hands of his enemies, McColloch turned to the cliff and spurred his horse over the edge. Alternate accounts claim the hill had either a 150 or 300 ft vertical descent.[3][7] In any case the cliff face was steep and dangerous for all but a very skilled (or very desperate) horseman. McColloch's horse leapt over the edge and after the initial decent was able to find its footing. Then, "the remainder of the distance was slid and scrambled over until they reached the bottom alive and uninjured."[3] As McColloch and his horse forded through Wheeling Stream and fled over the opposite bank, the Natives looked on without continuing their pursuit or firing shots.[6]

With Fort Henry's garrison reinforced, the Natives looted and burned the 25 cabins outside of the fort, stole or slaughtered 300 cattle, and then retreated the following day.[3]

Critcizing the Legend[edit]

Legendary tales frequently use hyperbole to glorify the feats of the hero and demonize the opponents. The referenced versions of this story are no exception, making it somewhat difficult to ascertain fact from fiction. This is compounded the fact that no American settlers saw the event and there is no Native American account of the siege. Samuel McColloch is the sole source, and his original telling was not written down. Specific criticisms follow:

The legendary version of Samuel McColloch describes him as well-known frontiersman much feared and admired by his Native American foes at the time of the Leap. The historic record for Samuel McColloch begins in 1777.[3]

The cliff is alternatively described as 150 ft or 300 ft. The vertical height of the leap also varies, with drawings showing a magnificent leap into the air, and the most modest retelling implying as 75 ft drop before a scramble down the rest of the hill.[3][7] Horses can sustain serious injury from jumps at heights of 1.2 m (4 ft).[8] The truth is impossible to know without speculation, but the lack of injury to the horse implies that a scramble down a very steep slope is the most likely scenario.

Natives are treated stereotypically, in particular the story speculates that they want to capture McColloch alive to conduct a human sacrifice.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ Olmstead, Earl P. (1991). Blackcoats Among the Delaware: David Zeisberger on the Ohio Frontier. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-434-6.

- ^ "Murray Treaty of Longueuil (1760)". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Biography: Samuel McColloch > Research | Ohio County Public Library | Ohio County Public Library | Wheeling West Virginia | Ohio County WV | Wheeling WV History |". www.ohiocountylibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ a b "The Fort Henry Story by Klein and Cooper > Research | Ohio County Public Library | Ohio County Public Library | Wheeling West Virginia | Ohio County WV | Wheeling WV History |". www.ohiocountylibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ Puryear, Robert B. III (May 2009). Border Forays and Adventures. Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-4489-0.

- ^ a b c "McColloch's Leap > Research | Ohio County Public Library | Ohio County Public Library | Wheeling West Virginia | Ohio County WV | Wheeling WV History |". www.ohiocountylibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ a b HISTORY OF THE PAN-HANDLE, West Virginia, 1879, by J. H. Newton, G. G. Nichols, and A. G. Sprankle. Pages 134-135.

- ^ Meershoek, L. S.; Schamhardt, H. C.; Roepstorff, L.; Johnston, C. (April 2001). "Forelimb tendon loading during jump landings and the influence of fence height". Equine Veterinary Journal. Supplement. 33 (33): 6–10. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.2001.tb05349.x. PMID 11721571.