McKelvey diagram

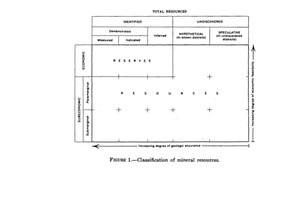

A McKelvey diagram or McKelvey box is a visual representation used to describe a natural resource such as a mineral or fossil fuel, based on the geologic certainty of its presence and its economic potential for recovery. The diagram is used to estimate the uncertainty and risk associated with availability of a natural resource.[3][4][5] As geological assurance of a resource's occurrence decreases, risk increases. As economic recoverability of a resource decreases, risk also increases.[3][2]

Meaning of the diagram[edit]

The terminology used may vary somewhat,[6][7] but resources in a McKelvey diagram fall into three main areas:[8]

- Reserves, which are already discovered and commercially-viable mineral deposits,[8][1]

- Contingent[8] or conditional[1] resources, whose existence is known but which are not commercially viable at present,

- Prospective[8] or undiscovered[1] resources that might exist but have not been found.

Natural resources are classified in two dimensions, with geologic certainty shown horizontally and economic viability shown vertically. As described by McKelvey in 1976, geological certainty may be categorized as Demonstrated (directly measured), Inferred (based on strong indirect evidence such as seismic data and detailed knowledge of the local geology) or Hypothetical & Speculative (based on limited or very general geological knowledge). Financially, recovery of a resource is categorized as either profitable or Economic to recover at today's price with today's technology, or not profitable and Subeconomic.[3][2]

The conditions represented by a McKelvey diagram are dynamic in nature: geological and technological knowledge and economic conditions are all subject to change over time. They are also inter-related: for example, lower availability of a natural resource may increase prices, which in turn may mean that a previously unprofitable technology is now considered viable.[3]

History[edit]

The diagram was introduced in 1972 by American geologist Vincent Ellis McKelvey, the 9th Director of the United States Geological Survey.[9][10] It was jointly adopted for use by the Geological Survey and the United States Bureau of Mines in 1973.[4]

Impact[edit]

Most current classification systems are based on the McKelvey diagram with its distinction between reserves and resources. The basic diagram has been adopted, modified and expanded by a various groups in multiple ways.[6] An even more minimalist version than the original, referred to as the Total Resource Box, has been "simplified and modified to make it more understandable to politicians and laypersons."[11]

SPE[edit]

The Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) has built upon the McKelvey diagram for use in the fossil fuels industry. SPE has worked with the World Petroleum Congress and the American Association of Petroleum Geologists to further develop the SPE/WPC/AAPG Petroleum Resource Classification System.[12] First SPE added levels of field project status relating to possible levels of risk.[13] Other modifications introduced a further subcategory, dividing reserves into proved (P1), probable (P2) and possible (P3) reserves.[12][14] A number of recommendations have been made towards standardizing and improving petroleum reporting.[6] However, as recently as 2012, the use of terms in reports from different oil companies and countries has been noted to be "inconsistent", with identical terms used to refer "to entirely different aspects."[7]

CRIRSCO[edit]

Another system that draws on the McKelvey diagram is the CRIRSCO Template or International Template for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves, developed by the international Committee for Mineral Reserves International Reporting Standards (CRIRSCO). The CRIRSCO Template attempts to standardize terms both internationally and between fields, particularly the mining and petroleum industries.[15][16][17]

UNFC[edit]

The United Nations Framework Classification for Resources (UNFC) incorporates elements from the McKelvey diagram and other systems. UNFC explicitly identifies three dimensions for assessing projects, each containing multiple levels. The UNFC dimensions are: (E) Economic and commercial viability, (F) Field project status and feasibility, and (G) Geological knowledge. The G-E dimensions of UNFC and the McKelvey diagram correspond.[18]

Each point in the 3-dimensional classification is described by a numeric code. The sequence used is always EFG, with “1” indicating the highest quality in a given dimension. The highest quality level would be "1:1:1", indicating that something is economically and commercially recoverable (E1), justified to be technically recoverable (F1) and has a reasonably assured geology (G1).[6]

The UNFC approach can be used to compare and harmonize different systems of classification.[18] An updated version of UNFC was released in 2019. It is compatible with sustainable management practices and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.[19]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Brobst, Donald A.; Pratt, Walden P.; McKelvey, V. E. (1973). Summary of United States mineral resources (PDF). Washington: United States Department of the Interior, Geological Survey. p. 4. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Kleppe, Thomas S.; McKelvey, V. E. (1976). Principles of the mineral resource classification system of the U.S. Bureau of Mines and U.S. Geological Survey : Geological Survey Bulletin 1450-A (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. A2. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Rogner, H-H. (November 1997). "An assessment of world hydrocarbon resources". Annual Review of Energy and the Environment. 22 (1): 217–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.22.1.217. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b Grenon, M (November 1977). "Global Energy Resources". Annual Review of Energy. 2 (1): 67–94. doi:10.1146/annurev.eg.02.110177.000435.

- ^ Sheldon, R. P. (1976). "Estimates of undiscovered petroleum resources--A perspective". U. S. Geol . Survey Annual Report Fiscal Year 1975. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Department of the Interior. pp. 11–21. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Etherington, John; Pollen, Torbjorn; Zuccolo, Luca (2005). "Mapping" Subcommittee Final Report – December 2005 Comparison of Selected Reserves and Resource Classifications and Associated Definitions (PDF). Society of Petroleum Engineers. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b McGlade, C.E. (November 2012). "A review of the uncertainties in estimates of global oil resources". Energy. 47 (1): 262–270. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2012.07.048. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Matt. "McKelvey's reserves and resources". Agile* Blog: Views and news about geoscience and technology. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ McKelvey, V. E. (1972). "Mineral Resource Estimates and Public Policy: Better Methods for Estimating the Magnitude of Potential Mineral Resources Are Needed to Provide the Knowledge That Should Guide the Design of Many Key Public Policies". American Scientist. 60 (1): 32–40. JSTOR 27842943. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ Theobald, P.K.; Schweinfurth, Stanley P.; Duncan, Donald Cave (1972). Energy resources of the United States Circular 650 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey. p. 2. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Wellmer, Friedrich-W.; Scholz, Roland (4 June 2017). "Putting Phosphorus First: The Need to Know and Right to Know Call for a Revised Hierarchy of Natural Resources". Resources. 6 (2): 20. doi:10.3390/resources6020020.

- ^ a b Mabro, Robert (2006). Oil in the 21st century : issues, challenges and opportunities. Oxford: Published by the Oxford University Press for the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. p. 139. ISBN 978-0199207381. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Guidelines for the evaluation of petroleum reserves and resources (PDF). United States: Society of Petroleum Engineers of AIME (TX). 2001. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-55563-105-5. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Thompson, E; Sorrell, S; Speirs, J (2009). UKERC Review of Evidence on Global Oil Depletion: Technical Report 2: Definition and interpretation of reserve estimates (UKERC/WP/TPA/2009/017) (PDF). London: UK Energy Research Centre. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Stephenson, P R; Weatherstone, N (2006). "Developments in International Mineral Resource and Reserve Reporting". International Mine Management Conference 2006 (PDF). Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Weatherstone, Niall (2007). The present and future of international resource and reserve reporting (PDF). Retrieved 3 September 2021.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "The International Reporting Template" (PDF). CRIRSCO.com. CRIRSCO. November 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b The United Nations Framework Classification (UNFC) for Energy and Mineral Resources (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ UNECE. "United Nations Framework Classification for Fossil Energy and Mineral Reserves and Resources 2019 Update".