Gliese 436

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Leo[1] |

| Right ascension | 11h 42m 11.09334s[2] |

| Declination | +26° 42′ 23.6508″[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 10.67[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M2.5 V[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (B) | ~12.20[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | ~10.68[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (J) | 6.900 ± 0.024[5] |

| Apparent magnitude (H) | 6.319 ± 0.023[5] |

| Apparent magnitude (K) | 6.073 ± 0.016[5] |

| U−B color index | +1.23[6] |

| B−V color index | +1.52[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +8.87±0.16[2] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 895.088(26) mas/yr[2] Dec.: −813.550(25) mas/yr[2] |

| Parallax (π) | 102.3014 ± 0.0302 mas[2] |

| Distance | 31.882 ± 0.009 ly (9.775 ± 0.003 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 10.63[3] |

| Details[7] | |

| Mass | 0.425±0.009 M☉ |

| Radius | 0.432±0.011 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.02463±0.00029 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.833±0.013[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 3,477+46 −44 K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | -0.46+0.31 −0.24[8] dex |

| Rotation | 39.9±0.8 d[9] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 1.0[10] km/s |

| Age | 7.41–11.05[11] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

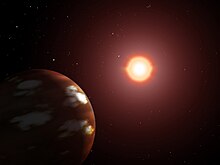

Gliese 436 is a red dwarf located 31.9 light-years (9.8 parsecs) away in the zodiac constellation of Leo. It has an apparent visual magnitude of 10.67,[3] which is much too faint to be seen with the naked eye. However, it can be viewed with even a modest telescope of 2.4 in (6 cm) aperture.[12] In 2004, the existence of an extrasolar planet, Gliese 436 b, was verified as orbiting the star. This planet was later discovered to transit its host star.

Nomenclature

[edit]The designation Gliese 436 comes from the Gliese Catalogue of Nearby Stars. This was the 436th star listed in the first edition of the catalogue.

In August 2022, this planetary system was included among 20 systems to be named by the third NameExoWorlds project.[13] The approved names, proposed by a team from the United States, were announced in June 2023. Gliese 436 is named Noquisi and its planet is named Awohali, after the Cherokee words for "star" and "eagle".[14]

Properties

[edit]Gliese 436 is a M2.5V star,[3] which means it is a red dwarf. Stellar models give both an estimated mass and size of about 43% that of the Sun. The same model predicts that the outer atmosphere has an effective temperature of 3,480 K,[7] giving it the orange-red hue of an M-type star.[15] Small stars such as this generate energy at a low rate, giving it only 2.5% of the Sun's luminosity.[7]

Gliese 436 is older than the Sun by several billion years and it has an abundance of heavy elements (with masses greater than helium-4) less than half%[16] that of the Sun. The projected rotation velocity is 1.0 km/s, and the chromosphere has a low level of magnetic activity.[3] Gliese 436 is a member of the "old-disk population" with velocity components in the galactic coordinate system of U=+44, V=−20 and W=+20 km/s.[3]

Planetary system

[edit]The star is orbited by one known planet, designated Gliese 436 b. The planet has an orbital period of 2.6 Earth days and transits the star as viewed from Earth. It has a mass of 22.2 Earth masses and is roughly 55,000 km in diameter, giving it a mass and radius similar to the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune in the Solar System. In general, Doppler spectroscopy measurements do not measure the true mass of the planet, but instead measure the product m sin i, where m is the true mass and i is the inclination of the orbit (the angle between the line-of-sight and the normal to the planet's orbital plane), a quantity that is generally unknown. However, for Gliese 436 b, the transits enable the determination of the inclination, as they show that the planet's orbital plane is very nearly in the line of sight (i.e. that the inclination is close to 90 degrees). Hence the mass quoted is the actual mass. The planet is thought to be largely composed of hot ices with an outer envelope of hydrogen and helium, and is termed a "hot Neptune".[17]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b / Awohali | 21.36+0.20 −0.21 M🜨 |

0.028±0.01 | 2.64388±0.00006 | 0.152+0.009 −0.008 |

85.80+0.25 −0.21° |

4.33 ± 0.18 R🜨 |

GJ 436 b's orbit is likely misaligned with its star's rotation.[19] In addition the planet's orbit is eccentric. Because tidal forces would tend to circularise the orbit of the planet on short timescales, this suggested that Gliese 436 b is being perturbed by an additional planet orbiting the star.[20]

Claims of additional planets

[edit]In 2008, a second planet, designated "Gliese 436 c" was claimed to have been discovered, with an orbital period of 5.2 days and an orbital semimajor axis of 0.045 AU.[21] The planet was thought to have a mass of roughly 5 Earth masses and have a radius about 1.5 times larger than the Earth's.[22] Due to its size, the planet was thought to be a rocky, terrestrial planet.[23] It was announced by Spanish scientists in April 2008 by analyzing its influence on the orbit of Gliese 436 b.[22] Further analysis showed that the transit length of the inner planet is not changing, a situation which rules out most possible configurations for this system. Also, if it did orbit at these parameters, the system would be the only "unstable" orbit on UA's Extrasolar Planet Interactions chart.[24] The existence of this "Gliese 436 c" was thus regarded as unlikely,[25] and the discovery was eventually retracted at the Transiting Planets conference in Boston, 2008.[26]

Despite the retraction, studies concluded that the possibility that there is an additional planet orbiting Gliese 436 remained plausible.[27] With the aid of an unnoticed transit automatically recorded at NMSU on January 11, 2005, and observations by amateur astronomers, it has been suggested that there is a trend of increasing inclination of the orbit of Gliese 436 b, though this trend remains unconfirmed. This trend is compatible with a perturbation by a planet of less than 12 Earth masses on an orbit within about 0.08 AU of the star.[28]

In July 2012, NASA announced that astronomers at the University of Central Florida, using the Spitzer Space Telescope, strongly believed they had observed a second planet.[29] This candidate planet was given the preliminary designation UCF-1.01, after the University of Central Florida.[30] It was measured to have a radius of around two thirds that of Earth and, assuming an Earth-like density of 5.5 g/cm3, was estimated to have a mass of 0.3 times that of Earth and a surface gravity of around two thirds that of Earth. It was thought to orbit at 0.0185 AU from the star, every 1.3659 days. The astronomers also believed they had found some evidence for an additional planet candidate, UCF-1.02, which is of a similar size, though with only one detected transit its orbital period is unknown.[31] Follow up observations with the Hubble Space Telescope as well as a reanalysis of the Spitzer Space Telescope data were unable to confirm these planets.[32][33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Roman, Nancy G. (1987). "Identification of a Constellation From a Position". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 99 (617): 695–699. Bibcode:1987PASP...99..695R. doi:10.1086/132034. Vizier query form Archived 2019-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Butler, R. Paul; et al. (2004). "A Neptune-Mass Planet Orbiting the Nearby M Dwarf GJ 436". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 580–588. arXiv:astro-ph/0408587. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..580B. doi:10.1086/425173. S2CID 118893640.

- ^ a b Reid, I. Neill; Cruz, Kelle L.; Allen, Peter R.; Mungall, Finlay; Kilkenny, David; Liebert, James; Hawley, Suzanne L.; Fraser, Oliver J.; Covey, Kevin R.; Lowrance, Patrick; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Burgasser, Adam J. (2004). "Meeting the Cool Neighbors. VIII. A Preliminary 20 Parsec Census from the NLTT Catalogue". The Astronomical Journal (Submitted manuscript). 128 (1): 463. arXiv:astro-ph/0404061. Bibcode:2004AJ....128..463R. doi:10.1086/421374. S2CID 28314795.

- ^ a b c Cutri, R. M.; et al. (June 2003), 2MASS All Sky Catalog of point sources, NASA/IPAC, Bibcode:2003tmc..book.....C

- ^ a b "Gliese 436". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- ^ a b c Pineda, J. Sebastian; et al. (September 2021). "The M-dwarf Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Sample. I. Determining Stellar Parameters for Field Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 918 (1): 23. arXiv:2106.07656. Bibcode:2021ApJ...918...40P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac0aea. S2CID 235435757. 40.

- ^ a b Wang, Xian-Yu; et al. (1 July 2021). "Transiting Exoplanet Monitoring Project (TEMP). VI. The Homogeneous Refinement of System Parameters for 39 Transiting Hot Jupiters with 127 New Light Curves". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 255 (1). 15. arXiv:2105.14851. Bibcode:2021ApJS..255...15W. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ac0835. S2CID 235253975.

- ^ Suárez Mascareño, A.; et al. (September 2015), "Rotation periods of late-type dwarf stars from time series high-resolution spectroscopy of chromospheric indicators", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 452 (3): 2745–2756, arXiv:1506.08039, Bibcode:2015MNRAS.452.2745S, doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1441, S2CID 119181646.

- ^ Jenkins, J. S.; et al. (October 2009), "Rotational Velocities for M Dwarfs", The Astrophysical Journal, 704 (2): 975–988, arXiv:0908.4092, Bibcode:2009ApJ...704..975J, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/704/2/975, S2CID 119203469

- ^ Saffe, C.; Gómez, M.; Chavero, C. (2006). "On the Ages of Exoplanet Host Stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 443 (2): 609–626. arXiv:astro-ph/0510092. Bibcode:2005A&A...443..609S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053452. S2CID 11616693.

- ^ Sherrod, P. Clay; Koed, Thomas L. (2003), A Complete Manual of Amateur Astronomy: Tools and Techniques for Astronomical Observations, Astronomy Series, Courier Dover Publications, p. 9, ISBN 0486428206, archived from the original on 2023-08-12, retrieved 2016-10-11

- ^ "List of ExoWorlds 2022". nameexoworlds.iau.org. IAU. 8 August 2022. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "2022 Approved Names". nameexoworlds.iau.org. IAU. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "The Colour of Stars", Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, December 21, 2004, archived from the original on 2012-03-18, retrieved 2012-01-16

- ^ Bean, Jacob L.; Benedict, G. Fritz; Endl, Michael (2006). "Metallicities of M Dwarf Planet Hosts from Spectral Synthesis". The Astrophysical Journal (abstract). 653 (1): L65 – L68. arXiv:astro-ph/0611060. Bibcode:2006ApJ...653L..65B. doi:10.1086/510527. S2CID 16002711.—for the metallicity, note that or 48%

- ^ Gillon, M.; et al. (2007). "Detection of transits of the nearby hot Neptune GJ 436 b". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 472 (2): L13 – L16. arXiv:0705.2219. Bibcode:2007A&A...472L..13G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077799. S2CID 13552824.

- ^ Trifonov, Trifon; Kürster, Martin; Zechmeister, Mathias; Tal-Or, Lev; Caballero, José A.; Quirrenbach, Andreas; Amado, Pedro J.; Ribas, Ignasi; Reiners, Ansgar; et al. (2018). "The CARMENES search for exoplanets around M dwarfs. First visual-channel radial-velocity measurements and orbital parameter updates of seven M-dwarf planetary systems". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 609. A117. arXiv:1710.01595. Bibcode:2018A&A...609A.117T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731442. S2CID 119340839.

- ^ Knutson, Heather A. (2011). "A Spitzer Transmission Spectrum for the Exoplanet GJ 436b". Astrophysical Journal. 735, 27 (1): 27. arXiv:1104.2901. Bibcode:2011ApJ...735...27K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/735/1/27. S2CID 18669291.

- ^ Deming, D.; et al. (2007). "Spitzer Transit and Secondary Eclipse Photometry of GJ 436b". The Astrophysical Journal. 667 (2): L199 – L202. arXiv:0707.2778. Bibcode:2007ApJ...667L.199D. doi:10.1086/522496. S2CID 13349666.

- ^ Ribas, I.; Font-Ribera, S. & Beaulieu, J. P. (2008). "A ~5 M⊙ Super-Earth Orbiting GJ 436?: The Power of Near-Grazing Transits". The Astrophysical Journal. 677 (1): L59 – L62. arXiv:0801.3230. Bibcode:2008ApJ...677L..59R. doi:10.1086/587961. S2CID 14132568.

- ^ a b "Smallest planet outside solar system found". Reuters. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2023-06-07.

- ^ "New Super-Earth is Smallest Yet". Space.com. 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ^ Extrasolar Planet Interactions Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alonso, R.; et al. (2008). "Limits to the planet candidate GJ 436c". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 487 (1): L5 – L8. arXiv:0804.3030. Bibcode:2008A&A...487L...5A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810007. S2CID 119194288.

- ^ Schneider, J. "Planet GJ 436 b". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ Bean, J. L. & Seifahrt, A. (2008). "Observational Consequences of the Recently Proposed Super-Earth Orbiting GJ436". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 487 (2): L25 – L28. arXiv:0806.3270. Bibcode:2008A&A...487L..25B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810278. S2CID 14811323.

- ^ Coughlin, J. L.; et al. (2008). "New Observations and a Possible Detection of Parameter Variations in the Transits of Gliese 436b". The Astrophysical Journal. 689 (2): L149 – L152. arXiv:0809.1664. Bibcode:2008ApJ...689L.149C. doi:10.1086/595822. S2CID 14893633.

- ^ "Alien exoplanet smaller than Earth discovered". Sydney Morning Herald. Reuters. July 2012. Archived from the original on 2014-04-11. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ Powers, Scott (July 18, 2012). "Planet UCF 1.01 is introduced to the world of astronomy". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Stevenson, Kevin B.; et al. (2012). "Two nearby sub-Earth-sized exoplanet candidates in the GJ 436 system". The Astrophysical Journal. 755 (1). 9. arXiv:1207.4245. Bibcode:2012ApJ...755....9S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/755/1/9. S2CID 118678765.

- ^ Stevenson, Kevin B.; et al. (2014). "A Hubble Space Telescope Search for a Sub-Earth-sized Exoplanet in the GJ 436 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 796 (1). 32. arXiv:1410.0002. Bibcode:2014ApJ...796...32S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/796/1/32. S2CID 118412895.

- ^ Lanotte, A. A.; et al. (2014). "A global analysis of Spitzer and new HARPS data confirms the loneliness and metal-richness of GJ 436 b". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 572. A73. arXiv:1409.4038. Bibcode:2014A&A...572A..73L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424373. S2CID 55405647. Archived from the original on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

External links

[edit]- "Gliese 436 / AC+27 28217". Sol Company. Archived from the original on 2015-09-13. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- "GJ 436". l'Observatoire de Paris. Archived from the original on 2012-04-01. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- "New Planet Found: Molten "Mars" Is "Right Around the Corner"". National Geographic. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-20.