Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study

The Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study was a scientific experiment in Canada on the effects of alcohol warning labels, terminated after lobbying from the alcohol industry, then relaunched with experimental design changes (omitting the "Alcohol can cause cancer" label, and some products) which a lead author said "watered down" the study and diluted its scientific value. The termination received international attention.[1][2]

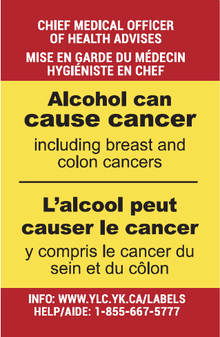

In November 2017, "Alcohol can cause cancer" warning labels (and two other designs) were added to alcoholic products at a liquor store in Yellowknife, next to existing federally-mandated 1991 warnings (about drinking while pregnant, or driving drunk). The labels were added as part of a study planned to run for eight months.[2][3][4] Alcohol industry lobbyists stopped the study after four weeks, with fears they would sue the Yukon government. The Association of Canadian Distillers, Beer Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association alleged that the Yukon government had no legislative authority to add the labels, and would be liable for defamation, defacement, damages (including damage to brands), and packaging trademark and copyright infringement, because the labels had been added without their consent.[6] They also claimed that the labels violated their freedom of expression.[7] Partly because cigarrette-package warning labels had already been ruled legal, these claims are not considered to have merit; the lobbyists could sue, but don't have a sound case.[5][7] In an interview with the New York Times, the lobby groups denied threatening legal action.[5]

John Streicker, the Yukon Minister Responsible for the Yukon Liquor Corporation, stopped the study. He said he did not believe the lobbyist's claims about the medical facts, and believed his chief medical officer of health, that the labels were truthful. He said he stopped the study because he did not wish Yukon to risk a long and expensive lawsuit, and thought leadership should be taken by the federal government after the COVID-19 pandemic.[2][3] Initially, the Yukon Liquor Corporation declined to identify the lobbyists who had contacted them.[3] A access to information request later published e-mails (see § External links) between lobbyists and the Liquor Corporation.[8]

Study design

Background

The study was started by university researchers from the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, with support from Health Canada, Public Health Ontario, the Chief Medical Officer of Health of the Yukon (Brendan Hanley[4]), and the Yukon Liquor Corporation.[2][3] In the Yukon as in most of Canada, there is a alcohol monopoly, where only the Yukon Liquor Corporation, controlled by the government, can sell alcohol. The Yukon Liquor Corporation was the only liquor retailer in Canada willing to take part in the study.[5]

Before the study started, consumers were surveyed, and strongly approved of putting more information on alcohol containers.[4]

The cancer labels were a global first. At the time of the study, South Korea warned consumers specifically about liver cancer,[9] and allowed manufacturers to choose between three labels, one of which did not mention cancer.[10] No other country had alcohol-cancer warning labels.[9] Ireland introduced mandatory cancer-risk labelling in 2018. As of 2020[update], no other countries had implemented cancer warning labels on alcohol.[10]

As of 2020[update], 47 countries mandate alcohol warning labels, mostly warnings against drinking while pregnant and driving while drunk. Eight required labelling of "standard drink" serving sizes, and none mandate information on drinking guidelines, although such knowledge has been shown to reduce drinking.[11]

Label design

The researchers thought that past alcohol warning labels hadn't been very well-designed. They designed the labels used in the study to have bright, attention-getting colours, clear messages, and a "large enough font size to be actually readable".[12] All of these factors have been shown, in lab and online studies, to make labels more effective.[7] Three labels were planned to rotate, as this has been found to make other warning labels more noticeable than always using the same label. The number of rotating labels was later reduced to two by industry intervention.[10] The yellow central background and red borders were intended to make them stand out in contrast to any container.[10] Label design work lasted four years, according to Tim Stockwell.[12]

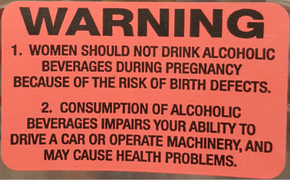

Yukon and the Northwest Territories had both brought in mandatory small stick-on post-manufacturer labels in 1991, well before the study began (see images). Both warn against drinking during pregnancy; the NWT label also warned of impaired ability to operate machinery and unspecified health problems. No other Canadian jurisdiction had any mandated alcohol warning labels at the time.[13]

Label designs were changed before the study began, in response to the Yukon Liquor Corporation. Researchers were given label-size limitations. So the fetal alcohol syndrome labels were removed when the other labels were put on, to keep the total label size down.[14] Tim Stockwell said that the original study design had included a pregnancy warning on the experimental labels, "but the (Yukon) Liquor Corporation kept insisting that the labels should be smaller, smaller, smaller and then in two languages, and there was just no room".[15]

Five focus groups done in the Yukon, before the labelling phase of the study began, found strong support for warning labels, with participants focussing on consumer's right to know about health harms, including cancer and fetal alcohol syndrome. Participants also wanted standard drink (SD) information, national low-risk drinking guidelines presented as a chart with pictograms; they favoured large labels.[7][16] Previous surveys generally found a majority of Canadians support alcohol warning labels, though one 2020 survey of the general public and "policy influencers" in Alberta and Quebec found that most preferred other methods.[7]

While there has been a lot of research on how people react after seeing alcohol labels in lab and online studies, and what they say about their future intentions, there is much less research on how people change their behaviour in response to real-world warnings. Most of the evidence on real-world warnings is based on the small, black-and-white, text-based labels required by the 1988 US Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act. They warn only about not drinking under specific circumstances, with messages about impaired driving and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.[17][18] Tim Stockwell, one of the researchers designing the study, described this evidence as "pretty moot because the labels are so bad."[18] Research suggests that the current American fetal warnings aren't very effective. Many people don't notice them.[7]

The messages chosen by alcohol providers as part of voluntary warning label schemes tend to be unhelpful (they are thought to be unlikely to change knowledge, intentions, or behaviour). Some may even be counterproductive; adolescents become less opposed to drunkeness when exposed to “please drink responsibly” messages.[7]

Other awareness measures

Since studies have shown that it makes labels more effective, broader awareness campaigns were planned to run simultaneously: in-store signage and handouts, a website, a toll-free helpline, and radio spots to augment the label messages. Industry intervention meant that the in-store and radio messaging never happened.[10]

Lobbying

"Alcohol can cause cancer" label

Most people don't know that alcohol causes cancer, according to surveys in the 2010s and early 2020s. Learning that alcohol causes cancer causes most people to strongly support putting cancer warnings on alcohol containers. Knowing makes drinkers, including heavy drinkers, decide to consume less alcohol. They also become more likely to support other alcohol-related public health measures, like minimum unit pricing.[7]

The NTAL study was the first to look at the effects of warning labels in the real world, but lab and online studies have previously tested their effects. Cancer warnings have been shown to be more effective than warnings about liver damage, diabetes, mental illness and heart disease. People seem to already know that alcohol causes liver damage; but if they learn that alcohol causes cancer, they make a decision to drink less. Learning that alcohol causes diabetes and mental illness has a weaker but similar effect. Learning that alcohol causes heart disease may or may not change drinking intentions; the evidence is mixed.[10][19][7]

The strongest industry objections were to the "Alcohol can cause cancer" labels.[2] John Streicker said that "I think the preference of the producers is to not have labels, period, and not to have a label study. I think I’ve heard that from them, but I think it’s also fair to say that the thing they were most concerned about was the cancer label."[15]

It is common for alcohol industry spokespeople to assert that "alcohol causes cancer" statements are inaccurate, misleading, unproven, incomplete, and/or overreach. These assertions are often quoted in news media, sometimes without the context of the scientific evidence.[20]

In this case, Beer Canada president Luke Harford wrote that "'Alcohol can cause cancer' is a false and misleading statement".[2] Jan Westcott of the Association of Canadian Distillers[21] called the cancer-risk labels "alarmist and misleading".[22] Such claims were widely quoted in media coverage of the NTAL study, though not as widely as in media coverage of some other efforts to label alcohol.[20]

Researchers, public health officials, and the Yukon government all strongly defended the truth of the statement.[2] The researchers said that the fact that alcohol causes cancer has been well-known to researchers since the nineties, and would be well-known to the public were it not for industry interference and obfuscation.[12]

Alcohol industry representatives also repeatedly stated that the link between alcohol and cancer was too complex to tell the public about on a small label; this talking point has also been used in other cases.[20] The NTAL study found that people who remembered the "Alcohol can cause cancer' label were more likely to think that alcohol could cause cancer.[10] There was no evidence that people misunderstood the simple message.

Industry-made public relations materials tend to have much more complex messages about alcohol and cancer. They stress that alcohol isn't the only thing that causes cancer, and that there are many types of cancer which haven't been linked to alcohol (also true of tobbacco), and point out that it is not yet fully understood how alcohol causes cancers. These statements are true, but irrelevant. Industry materials also make or suggest untrue statements: for instance, the idea that alcohol only causes cancer in subgroups (like binge drinkers, heavy drinkers, smokers, people with nutritional deficiencies or taking HRT), or even that alcohol might protect smokers against cancer. They often incorrectly say that there is no cancer risk from light or moderate drinking. The evidence doesn't support these claims.[23] Industry statments often mix correct and incorrect information.[23]

Major industry strategies for fighting public knowledge of the link between alcohol and cancer have been catagorized as deny, distort, and distract: deny the link exists, or avoid mentioning it; misrepresent the link, by stating or implying that it is complex; and shift the discussion away from the effects on common cancers. Industry is especially keen to conceal the danger of colorectal and breast cancer.[7][24]

Industry reps also told media that cancer labels would hurt and disadvantage the alcohol industry, stigmatize it, and damage its reputation, often mentioning small/craft breweries and/or distilleries.[20] The researchers acknowledged that people who know that alcohol is carcinogenic seem to buy less alcohol, according to earlier studies, and that their research might well find evidence that the labels would reduce sales.

Threats

The Association of Canadian Distillers, Beer Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association alleged that the Yukon government had no legislative authority to add the labels, and would be liable for defamation, defacement, damages (including damage to brands), and packaging trademark and copyright infringement, because the labels had been added without their consent.[25]

In interviews with the New York Times, the lobby groups denied threatening legal action, while the minister said he had stopped the study because he feared it.[5] The Yukon Liquor Coporation put out a written statement saying that "The liquor industry indicated a possibility and/or likelihood of legal action."[12]

Robert Solomon, a Canadian law professor with 40 years' experience specializing in drug and alcohol policy, called the legal threats "without merit", and characterized them as an attempt to keep consumers unaware of the health costs of alcohol. He said it was clear that the Yukon government had the legal right to add the labels, because of the Supreme Court of Canada's past rulings on cigarette-package warning labels.[5] He also said that since the Yukon Liquor Corporation sells alcoholic drinks, it has a legal duty of care to warn consumers of potential risks, and "It doesn’t matter if the manufacturer isn’t convinced by the evidence."[26]

The researchers also disputed the idea that there was any ground for legal action, and said that the government might be at more legal risk for not warning about known dangers. In a later study report, they wrote "Since the scientific literature has been interpreted by international cancer experts as providing definitive proof of alcohol's causal role, such a [defamation] case could not be proven."[2] They also thought the alcohol industry, having actively intervened to conceal the health harms of their products from consumers, were opening themselves up to litigation for both the human suffering and recovery of healthcare costs.[12]

Complaints about lack of prior consultation with industry

Lobbyists complained that they had not been conasulted on or consented to the study.

John Streicker appeared to blame the researchers for not consulting with industry, saying "One of the things to understand first and foremost is that this is a set of researchers that approached us to do a study here in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories and we agreed... We did encourage them to talk directly with the producers and largely I want to say, we left that in their hands."[27]

Tim Stockwell argued that consulting with industry would have been pointless. "Our conversation would go something like this: 'We're thinking of a study putting labels on your alcohol containers about possible health effects' ...[and] they would say, 'no, you are not going to do that — we are going to stop you, and we will use all means at our disposal to stop that information getting out'".[27] He also argued that consultation would be unethical: "We don’t want to compromise the accuracy of the information that is put out to consumers because the people who are making a profit from the product are concerned."[15] He said it would be against rasearch ethics guidelines to discuss warning label design with people who have vested commercial interests in increasing alcohol sales.[27]

Lobbyist identities

Initially, the Yukon Liquor Corporation declined to identify the lobbyists who had contacted them.[3]

Investigative news program The National asked Beer Canada, the Association of Canadian Distillers, and the Canadian Vintners Association[32] if they accepted the link between alcohol and cancer, and felt a responsibility to inform consumers of the risk. All three evaded the question, speaking instead of responsibility and moderation, and Spirits Canada said that drinking alcohol had health benefits.[22]

An access to information request by freelance journalist James Wilt[2] later published e-mail correspondence () between the Liquor Corporation and some lobbyists (see sidebar).[8][1]

Luke Harford of Beer Canada suggested that the reduced-risk drinking limits guidelines might be interpreted as a safe amount to drink and drive, asking "Is YLC ready to take on that legal responsibility or is it planning to throw that at the supplier who was never given a chance to even see the label", and wrote "We strongly oppose any non-authorized alteration or defacing of our containers or packaging". He also stated that "The researchers you are working with are not interested in testing their hypothesis from an objective and scientific starting point. They already know the conclusions they are going to present.", citing the researchers' previous support for warning labels, and their opinions that its actions show that "the alcohol industry is itself a threat to public health".[33] The researchers rejected these accusations; Tim Stockwell said "We were accused of actually having decided what the results of our research would be in advance, which is impugning our reputation — utterly unfair. I've been put in print that at the present time there's no evidence that warning labels change behaviour. And if any study could have done this, this little study in the Yukon could have shown that in principle, there was a change in behaviour. We don't know. If we'd been able to complete the study, we'd have found out."[12]

Local alcohol producers also objected. The owner of the Yukon Shine Distillery, Karlo Krauzig, said he didn't see why alcohol should have warning labels when other products that harm health don't, such as sugary beverages. The president of Yukon Brewing, Bob Baxter, didn't think the Yukon government had the legal authority: "I mean, if I wandered down the aisle of a grocery store and started putting stickers on boxes of cereal at my own whim — I don't have the authority to do that".[15]

John Streicker, the responsible minister, said he had spoken to national interest groups and local alcohol producers. E-mails released under an access to information request contain discussion by lobbyists of the changes they considered necessary.[8][1]

Modified study

Why is it hardly anybody knows that alcohol causes cancer [30 years after the scientific evidence was broadly accepted]? This is the reason. Because when you try and put the message out there, it's squashed.

The study was restarted with the "Alcohol can cause cancer" warning labels removed from the rotation, and some alcohol products exempted.[8][1] The downscaled study was no longer allowed to add labels to products from small producers (including the local alcohol producers), or to smaller containers where the label might cover the product label or trademark, or to aluminum cans or beer bottles recycled locally (concerns were raised that the warning labels might hinder recycling in ways that the product labels did not).[15]

At the time when the study had been "paused", Jan Westcott of the Association of Canadian Distillers wrote to the Yukon Liquor Corporation (YLC): "We also confirm that, without prejudice to our views on the affixing of any labels by the YLC on our Members' products without their express authority, we would take no action in this regard should the YLC decide to continue to affix its current FASD labels. [Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder labels, the warnings against drinking while pregnant]". He later wrote saying: "We are pleased that the modified study will proceed without the alarmist and misleading "cancer" label. We understand from our conversations that the study will now use two labels, one communicating Canada's "Low-risk Drinking Guidelines" and another defining a "Standard drink". In order to minimize the risk of inadvertent trademark or other intellectual property infringement issues, we would appreciate the opportunity to review these [new] labels at the earliest opportunity."[34]

When the resumption of a reduced version of the study was announced, Tim Stockwell said that the "Alcohol can cause cancer" label was the most effective of the three, and eliminating it "diluted" the experiment. He also noted that the study was now shorter than planned and fewer products would be labelled, though he expessed hope that at least 70-80% of products would be labelled. He thought it was unlikely that the modified study would be powerful enough to provide clear evidence that the warning labels reduced harmful behaviour, downgrading the study to an awareness-raising exercise.[15]

The study researchers attributed several motives to the lobbyists; one was to avoid clear results. The researcher's goal was to determine whether a well-designed public-health campaign, including well-designed warning labels, could change behaviour, and cause people to drink less,[12] thus reducing the health harms of alcohol. This sort of evidence was important in convincing governments to bring in warning labels on nicotine products. The researchers expected that any effects would be weakend by the shortening of the study, the loss of the simplest and most effective message, "Alcohol causes cancer", the reduction of the number of different warning labels in rotation, and the cancellation of all of the aspects of the public health campaign other than the labels. Media coverage also meant that people in the control site heard about the campaign. All this made it harder for the studies to reach a clear conclusion and inform public health policy.

Results

-

A 6.31% decrease in the per-capita alcoholic drink consumption over the period after the first month of labelling, and an 9.97% decrease after the second period in which the warning labels were present, comparing treatment and control groups and adjusting for time of year and demographics. Lines mark dates on which labels were added; when labelling stiopped, some labelled products remained on the shelves until sold. Interpolation between monthly datapoints means that sales may have decreased a bit earlier or later, within the month, than is shown.

-

Two months after the first round of warning labels, many consumers remembered the cancer messages. The resumption of the study omitted the cancer warning labels; recall declined. About half of the same consumers were deliberatly followed-up and surveyed twice; the rest were new in the second survey. Researchers suspected that media coverage of the controversy around the trial increased knowledge of cancer risks in the study area and the control area.

-

The labels may have improved knowledge of official drinking guidelines, but the result was not statistically significant

Researchers found that consumers of alcohol at the stores generally were supportive of more warning labelling.[10] Behaviourally, sales of labelled products declined; sales of the small number of unlabelled products increased drastically, but as there weren't very many of those, overall sales still declined.[35] Results on increased awareness and knowledge of drinking guidelines had large confidence intervals, and at 95% CIs were not statistically significant. The shortened study and small sample sizes weakened the study's ability to find effects.[11]

A medical review paper described the "numerous publications on the Yukon project" as "exemplary".[7]

Publications

- Fulltext of published e-mails from lobbyists:

- obtained by FOI request "[Untitled]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2022.

- sent to University of Victoria Ken Beattie, Executive Director, BC Craft Brewers Guild. "Dr. Tim Stockwell – Yukon / NWT Northern Territories Alcohol Study – Ethics Board Approval Inquiry" (PDF). Retrieved 17 November 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Study design

- Vallance, Kate; Stockwell, Timothy; Hammond, David; Shokar, Simran; Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Greenfield, Thomas; McGavock, Jonathan; Zhao, Jinhui; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Hobin, Erin (10 January 2020). "Testing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Alcohol Warning Labels and Modifications Resulting From Alcohol Industry Interference in Yukon, Canada: Protocol for a Quasi-Experimental Study". JMIR Research Protocols. 9 (1): e16320. doi:10.2196/16320. PMC 6996737. PMID 31922493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - "Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study". nwtspor.ca. Hotıì Ts'eeda (research support unit).

- Vallance, Kate; Stockwell, Timothy; Hammond, David; Shokar, Simran; Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Greenfield, Thomas; McGavock, Jonathan; Zhao, Jinhui; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Hobin, Erin (10 January 2020). "Testing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Alcohol Warning Labels and Modifications Resulting From Alcohol Industry Interference in Yukon, Canada: Protocol for a Quasi-Experimental Study". JMIR Research Protocols. 9 (1): e16320. doi:10.2196/16320. PMC 6996737. PMID 31922493.

- Study results

- University press release with links "Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study - University of Victoria". UVic.ca.

- Paper summarizing a number of the papers produced by the study: Babor, Thomas F. (March 2020). "The Arrogance of Power: Alcohol Industry Interference With Warning Label Research". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 222–224. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.222. PMID 32359053. S2CID 218480278.

- Vallance, K; Romanovska, I; Stockwell, T; Hammond, D; Rosella, L; Hobin, E (1 January 2018). ""We Have a Right to Know": Exploring Consumer Opinions on Content, Design and Acceptability of Enhanced Alcohol Labels". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx068. PMID 29016716.

- Hobin, Erin; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Vallance, Kate; Hammond, David; McGavock, Jonathan; Greenfield, Thomas K.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Paradis, Catherine; Stockwell, Tim (March 2020). "Testing Alcohol Labels as a Tool to Communicate Cancer Risk to Drinkers: A Real-World Quasi-Experimental Study". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 249–261. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.249. PMC 7201213. PMID 32359056.

- Zhao, Jinhui; Stockwell, Tim; Vallance, Kate; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "The Effects of Alcohol Warning Labels on Population Alcohol Consumption: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 225–237. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.225. PMID 32359054. S2CID 218481829.

- Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Vallance, Kate; Stockwell, Tim; Zhao, Jinhui; Hammond, David; McGavock, Jonathan; Greenfield, Thomas K.; Paradis, Catherine; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "Examining the Impact of Alcohol Labels on Awareness and Knowledge of National Drinking Guidelines: A Real-World Study in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 262–272. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.262. PMC 7201209. PMID 32359057.

- Vallance, Kate; Vincent, Alexandria; Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Stockwell, Tim; Hammond, David; Greenfield, Thomas K.; McGavock, Jonathan; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "News Media and the Influence of the Alcohol Industry: An Analysis of Media Coverage of Alcohol Warning Labels With a Cancer Message in Canada and Ireland". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 273–283. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.273. PMC 7201216. PMID 32359058.

- Stockwell, Tim; Solomon, Robert; O’Brien, Paula; Vallance, Kate; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "Cancer Warning Labels on Alcohol Containers: A Consumer's Right to Know, a Government's Responsibility to Inform, and an Industry's Power to Thwart". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 284–292. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.284. PMID 32359059. S2CID 218481696.

- Vallance, K; Stockwell, T; Zhao, J; Shokar, S; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N; Hammond, D; Greenfield, TK; McGavock, J; Weerasinghe, A; Hobin, E (March 2020). "Baseline Assessment of Alcohol-Related Knowledge of and Support for Alcohol Warning Labels Among Alcohol Consumers in Northern Canada and Associations With Key Sociodemographic Characteristics". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 238–248. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.238. PMC 7201212. PMID 32359055.

- Hobin, E; Shokar, S; Vallance, K; Hammond, D; McGavock, J; Greenfield, TK; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N; Paradis, C; Stockwell, T (October 2020). "Communicating risks to drinkers: testing alcohol labels with a cancer warning and national drinking guidelines in Canada". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 111 (5): 716–725. doi:10.17269/s41997-020-00320-7. PMC 7501355. PMID 32458295.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Taylor Blewett (17 February 2018). "Yukon alcohol label study will no longer include warnings of cancer link". Financial Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Windeyer, Chris (9 May 2020). "Booze industry brouhaha over Yukon warning labels backfired, study suggests". CBC News. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Liquor industry calls halt to cancer warning labels on Yukon booze". CBC News. 28 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "New booze labels in Yukon warn of cancer risk from drinking". CBC News. 23 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Austen, Ian (6 January 2018). "Yukon Government Gives In to Liquor Industry on Warning Label Experiment". The New York Times.

- ^ defamation,[2][5][1] defacement,[3] damages,[3] and packaging trademark[3][5][1] and copyright infringement,[2] damage to brands,[5] consent[3]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Giesbrecht, N; Reisdorfer, E; Rios, I (16 September 2022). "Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Rapid Review with Action Recommendations". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (18): 11676. doi:10.3390/ijerph191811676. PMC 9517222. PMID 36141951.

- ^ a b c d Blake, Emily (6 May 2020). "Improved warning labels could curb drinking, Yukon study suggests". cabinradio.ca.

- ^ a b Joseph, Rebecca (23 November 2017). "'Alcohol can cause cancer': Yukon adds warning labels to liquor - National". Global News.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hobin, Erin; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Vallance, Kate; Hammond, David; McGavock, Jonathan; Greenfield, Thomas K.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Paradis, Catherine; Stockwell, Tim (March 2020). "Testing Alcohol Labels as a Tool to Communicate Cancer Risk to Drinkers: A Real-World Quasi-Experimental Study". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 249–261. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.249. PMC 7201213. PMID 32359056.

- ^ a b Schoueri-Mychasiw, Nour; Weerasinghe, Ashini; Vallance, Kate; Stockwell, Tim; Zhao, Jinhui; Hammond, David; McGavock, Jonathan; Greenfield, Thomas K.; Paradis, Catherine; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "Examining the Impact of Alcohol Labels on Awareness and Knowledge of National Drinking Guidelines: A Real-World Study in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 262–272. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.262. PMC 7201209. PMID 32359057.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Orff, Carol; Douglas, Jeff (18 May 2018). "Yukon alcohol study update". As it Happens. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. CBC News. Transcript. Additional partial transcript with commentary

- ^ Vallance, K; Stockwell, T; Hammond, D; Shokar, S; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N; Greenfield, T; McGavock, J; Zhao, J; Weerasinghe, A; Hobin, E (10 January 2020). "Testing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Alcohol Warning Labels and Modifications Resulting From Alcohol Industry Interference in Yukon, Canada: Protocol for a Quasi-Experimental Study". JMIR research protocols. 9 (1): e16320. doi:10.2196/16320. PMC 6996737. PMID 31922493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Booze warnings worked in U.S., says researcher after Yukon labels pulled". thestar.com. 3 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f yukon-news.com/news/yukons-alcohol-label-study-back-on-but-without- a-cancer-warning/ https://www. yukon-news.com/news/yukons-alcohol-label-study-back-on-but-without- a-cancer-warning/.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Vallance, K; Romanovska, I; Stockwell, T; Hammond, D; Rosella, L; Hobin, E (1 January 2018). ""We Have a Right to Know": Exploring Consumer Opinions on Content, Design and Acceptability of Enhanced Alcohol Labels". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx068. PMID 29016716.

- ^ Special Issue of Alcohol and Alcoholism: Hassan, L; Shiu, E (1 January 2018). "Communicating Messages About Drinking". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx112. PMID 29281048.

- ^ a b Wilt, James (16 January 2018). "It Was Only When I Quit Drinking That I Realized How Bad It Was For Me". www.vice.comCE Canada. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Jongenelis, MI; Pratt, IS; Slevin, T; Chikritzhs, T; Liang, W; Pettigrew, S (1 October 2018). "The effect of chronic disease warning statements on alcohol-related health beliefs and consumption intentions among at-risk drinkers". Health Education Research. 33 (5): 351–360. doi:10.1093/her/cyy025. PMID 30085037.

- ^ a b c d Vallance, K; Vincent, A; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N; Stockwell, T; Hammond, D; Greenfield, TK; McGavock, J; Hobin, E (March 2020). "News Media and the Influence of the Alcohol Industry: An Analysis of Media Coverage of Alcohol Warning Labels With a Cancer Message in Canada and Ireland". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 273–283. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.273. PMC 7201216. PMID 32359058.

- ^ Fulltext of published e-mails from lobbyists "[Untitled]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2022.

- ^ a b Roumeliotis, Ioanna; Witmer, Brenda (8 January 2022). "Alcohol should have cancer warning labels, say doctors and researchers pushing to raise awareness of risk". CBC News.

- ^ a b Petticrew, M; Maani Hessari, N; Knai, C; Weiderpass, E (March 2018). "The strategies of alcohol industry SAPROs: Inaccurate information, misleading language and the use of confounders to downplay and misrepresent the risk of cancer". Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (3): 313–315. doi:10.1111/dar.12677. PMC 5873370. PMID 29446154.

- ^ Petticrew, M; Maani Hessari, N; Knai, C; Weiderpass, E (March 2018). "How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/dar.12596. PMID 28881410. S2CID 892691.

- ^ defamation,[2][5][1] defacement,[3] damages,[3] and packaging trademark[3][5][1] and copyright infringement,[2] damage to brands,[5] consent[3]

- ^ Wilt, James (21 May 2018). "Alcohol-industry officials lobbied Yukon to halt warning-label study, e-mails show". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ a b c "Yukon alcohol producers say they were left in the dark about warning label study". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Beer Canada appoints industry veteran CJ Hélie as president". CPECN.

- ^ "Mr. Rowland Dunning (Executive Director, Canadian Association of Liquor Jurisdictions) at the Finance Committee". openparliament.ca.

- ^ "John Streicker". Yukon Legislative Assembly.

- ^ "Leadership shuffle in Government of Yukon departments". Government of Yukon. 17 January 2019.

- ^ referred to as Beer Canada, Spirits Canada and Wine Growers Canada in the source

- ^ "[Untitled]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2022.: 2, 3, 5

- ^ "[Untitled]" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2022.: 7, 10

- ^ Zhao, Jinhui; Stockwell, Tim; Vallance, Kate; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "The Effects of Alcohol Warning Labels on Population Alcohol Consumption: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 225–237. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.225. PMID 32359054. S2CID 218481829.