Unhappy triad

| Unhappy triad | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Terrible triad, horrible triangle, O'Donoghue's triad, the three musketeers [1] blown knee |

| |

| Knee | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

The unhappy triad, also known as a blown knee among other names, is an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, and meniscus. Analysis during the 1990s indicated that this 'classic' O'Donoghue triad is actually an unusual clinical entity among athletes with knee injuries. Some authors mistakenly believe that in this type of injury, "combined anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament (ACL- MCL) disruptions that were incurred during athletic endeavors" always present with concomitant medial meniscus injury. However, the 1990 analysis showed that lateral meniscus tears are more common than medial meniscus tears in conjunction with sprains of the ACL.[1]

Symptoms

[edit]- Pain in affected knee

- Stiffness and swelling in affected knee

- Catching or locking of the knee in affected knee

- Instability of the knee with twisting or side-to-side movements (The sensation of the knee "giving out").

- Inability to move the knee through its full range of motion

Cause

[edit]The unhappy triad occurs due to a lateral blow to the knee causing a rupture in the anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, and meniscus. Injury is most often sustained when a lateral (from the outside) force impacts the knee while the foot is fixed on the ground. The strong valgus or rotary force to the knee tears the ACL, MCL, and medial meniscus all together. This type of injury occurs often in contact sports such as football, rugby, or motocross. During the injury, the leg is laterally rotated and over-abducted. In about 10% of cases, the force is applied to the opposite side of the knee, and the lateral and posterolateral ligaments are torn.

Anatomy

[edit]

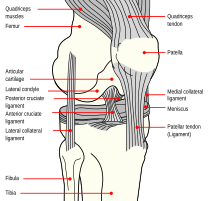

Skeletal components involved in the unhappy triad include: patella, femur, tibia. No muscles are directly involved in this injury, only ligaments; However, strengthening the hip flexor and hip extensor muscles may help alleviate the injury.

The medial collateral ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, anterior cruciate ligament, and lateral collateral ligament are the four primary ligaments of the knee. The medial and lateral collateral ligaments primarily provide support to varus and valgus forces whereas the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments prevent anterior and posterior translation of the tibia on the femur.[2]

Structures in triad

[edit]

The classic O'Donoghue triad is characterized by an injury to three knee structures (in order):

- the anterior cruciate ligament

- the medial meniscus (however, lateral meniscus[1] injuries are more commonly seen among athletes, leading to the definition of the O'Donoghue triad most commonly used today.) [3][4][5]

- the medial collateral ligament (or "tibial collateral ligament")

Component injuries

[edit]This section needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. In particular, it has problems with not using MEDMOS. (December 2017) |

The anterior cruciate ligament

[edit]The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the four crucial ligaments in the knee. It originates from the lateral condyle of the femur and goes to the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia. Its function is to provide stability in the knee and minimize stress across the knee joint. It also restrains excessive forward movement in the leg and limits rotational movements in the knee.

Injury

An anterior cruciate ligament injury results from excess tension on the ligament. This can come from a sudden stop or twisting motion of the knee. A few initial symptoms include swelling, knee instability, and pain. A popping sound or sensation may or may not be heard when the ACL first tears. A following symptom usually includes the feeling of the knee "giving out". Tearing of the ACL is the most significant injury because it leaves the knee unstable, which also causes the knee to lose its normal function.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 100,000 new anterior cruciate ligament injuries occur in the U.S. each year.[6] Approximately half of the new ACL injuries involve injuries to the ligament, tendon, and or muscle of that affected knee.[7] Women are at greater risk for ACL injuries than men due to their greater Q angle. The Q angle is the angle formed by a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine to central patella and a second line drawn from central patella to tibial tubercle.

Meniscus

[edit]

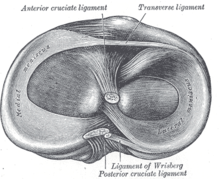

The medial meniscus is a C-wedge shaped piece of cartilage that acts as a"shock absorber" between the femur and the tibia. Each knee has two menisci, one at the outer edge and one at the inner edge of the knee. The menisci are tough and rubber-like to help cushion the joint and help keep it stable.

The lateral meniscus is also known as the external semilunar fibrocartilage. It is a fibrocartilage band on the lateral side of the knee joint and can easily be injured with torsional stress or direct force.

Each knee has a medial and lateral meniscus, consisting of connective tissue and collagen fibers. Menisci are needed to distribute the body weight across the knee. Without them, the body weight is distributed unevenly on the femur and tibia, possibly leading to early arthritis in the knee joint. The menisci are nourished by small blood vessels, but each has a large central section which is avascular and does not get a direct blood supply. This poses a problem in a meniscus injury, as blood flow is diminished and the avascular areas tend to not heal.

Injury

The tear of meniscus is among the most common knee injuries. It is usually caused by torsional stress; twisting or turning of the knee too quickly with the foot planted on the ground while the knee is flexed. The feeling of a "pop" in the knee is usually felt when the meniscus is torn. Athletes, particularly those who participate in contact sports, are at a greater risk for meniscal tears. Sports-related meniscal tears often occur with other knee injuries, such as an anterior cruciate ligament tear.

A torn meniscus is commonly referred to as torn cartilage in the knee. Menisci tear in different ways and are noted by how they look, as well as where the tear occurs in the meniscus. Two types of tears include minor, which includes stiffness and swelling within two to three days but usually goes away in two to three weeks. Then there is severe, which without treatment, a piece of meniscus may come loose and drift into the joint space. Tears include longitudinal, parrot-beak, flap, bucket handle, and mixed/complex.

Epidemiology

Injury to the medial meniscus is about five times greater than injury to the lateral meniscus due to its anatomical attachment to the MCL.[8] Lateral meniscal tears are more common in acute ACL injuries, whereas medial meniscal injuries are more common in chronic ACL-deficient knees and more amenable to repair.[9]

Meta-analysis shows that in acute injuries of the ACL associated with a meniscus tear, 44% were of the medial meniscus, whereas 56% were of the lateral meniscus; in chronic ACL insufficiency, 70% were medial whereas 30% were lateral.[10]

Medial collateral ligament

[edit]

Injury

Because the medial collateral ligament resists widening of the inside of the knee joint, the ligament is usually injured when the outside of the knee joint is struck. This force causes the outside of the knee to buckle, and the inside to widen. When the MCL is stretched too far, it is susceptible to tearing and injury. This is the injury seen by the action of "clipping" in a football game.

An injury to the MCL may occur as an isolated injury, or it may be part of a complex injury to the knee. Other ligaments ACL, or meniscus, may be torn along with a MCL injury.

Symptoms

The most common symptom following an MCL injury is pain directly over the ligament. Swelling over the torn ligament may appear, and bruising and generalized joint swelling are common 1 to 2 days after the injury. In more severe injuries, patients may complain that the knee feels unstable.

Treatment

Treatment of an MCL tear depends on the severity of the injury. Treatment always begins with allowing the pain to subside, beginning work on mobility, followed by strengthening the knee to return to sports and activities. Bracing can often be useful for treatment of MCL injuries. Fortunately, most often surgery is not necessary for the treatment of an MCL tear.

Treatments

[edit]

Treatment of the unhappy triad usually requires surgery. An ACL surgery is common and the meniscus can be treated during the surgery as well. The MCL is rehabilitated through time and immobilization. Physical therapy after the surgery and the use of a knee brace help speed up the healing process. A typical surgery for a blown knee includes:

- Patellar tendon autograft (An autograft is a graft that comes from the patient)

- Hamstring tendon autograft

- Quadriceps tendon autograft

- Allograft (taken from a cadaver) patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, semitendinosus, gracilis, or posterior tibialis tendon

The goal of reconstruction surgery is to prevent instability and restore the function of the torn ligament, creating a stable knee. There are certain factors that the patient must consider when deciding for or against surgery.

An important post-surgical treatment of unhappy triad is Physical Therapy (PT). PT includes exercise ambulatory programs, mobilizations, and modalities to help ease symptoms and speed up the recovery process. The purpose of physical therapy is strengthening muscle and increasing the knee's range of motion without damaging the new grafts.[11] Exercise ambulatory programs are prescribed by a Physical Therapist and should be used during recovery. Physical Therapist will provide immediate knee mobilization manually or with continuous passive motion (CPM) within the first week. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) should be used for a span of 6-8 weeks postoperative. Immediate cryotherapy could be used for treatment as well. A combination of functional tests and validated patient-reports are used to determine a patient’s readiness to return to activities.[12]

Epidemiology

[edit]A study containing 100 consecutive patients with a recent anterior cruciate ligament injury were examined with respect to type of sports activity that caused the injury. Of the 100 consecutive ACL injuries, there were also 53 medial collateral ligament injuries, 12 medial, 35 lateral and 11 bicompartmental meniscal lesions. 59/100 patients were injured during contact sports, 30/100 in downhill skiing and 11/100 in other recreational activities, traffic accidents or at work.[13]

An associated medial collateral ligament tear was more common in skiing (22/30) than during contact sports (23/59), whereas a bicompartmental meniscal lesion was found more frequently in contact sports (9/59) than in skiing (0/30). Weightbearing was reported by 56/59 of the patients with contact sports injuries whereas 8/30 of those with skiing injuries. Non-weightbearing in the injury situation led to the same rate of MCL tears (18/28) as weightbearing (35/72) but significantly more intact menisci (19/28 vs 23/72). Thus, contact sports injuries were more often sustained during weightbearing, with a resultant joint compression of both femuro-tibial compartments as shown by the higher incidence of bicompartmental meniscal lesions. The classic "unhappy triad" was a rare finding (8/100) and Fridén T, Erlandsson T, Zätterström R, Lindstrand A, and Moritz U. suggest that this entity should be replaced by the "unhappy compression injury".[13]

History

[edit]

In 1936, Cambell stated that an "impairment of the anterior crucial and medial ligaments is associated with injuries of the internal cartilage". In 1950, O'Donoghue described the unhappy triad as: (1) rupture of the medial collateral ligament, (2) damage to the medial meniscus and (3) rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. O'Donoghue estimated the incidence rate in the traumatic sports knee to be 25%.[3]

In 1991, Shelbourne and Nitz questioned the validity of O'Donoghue's terrible triad study. A review of all arthroscopically confirmed acute injuries of second degree or worse to the ACL and MCL was performed. Of the 52 knees reviewed, 80% of group 1 had lateral meniscus tears and 29% had associated medial meniscus tears. None of the medial meniscus tears were isolated; medial meniscus tears were not present in the absence of a lateral meniscus tear.[3] From this study, it was concluded that the structures more typically involved in a triad were the anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, and the lateral (not medial) meniscus.

Terminology

[edit]The term "unhappy triad" was coined by O'Donoghue in 1950.[3][14][15] However, since then, this term and the term "terrible triad" have also been used to describe several other combinations of joint injuries, including the terrible triad of the elbow[16] and shoulder.[17]

The term "terrible triad" is also sometimes used in the popular press to describe conditions relating to pain, or even to refer to the MacDonald triad of sociopathic behavior.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Shelbourne K, Nitz P (1991). "The O'Donoghue triad revisited: Combined knee injuries involving anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligament tears". Am J Sports Med. 19 (5): 474–7. doi:10.1177/036354659101900509. PMID 1962712. S2CID 45964892.

- ^ Winterstein, Andrew P. (2009). Athletic training student primer : a foundation for success (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: SLACK. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-55642-804-3.

- ^ a b c d Barber, FA (1992). "What is the terrible triad?". Arthroscopy. 8 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(92)90130-4. PMID 1550645.

- ^ Balmer K, Gunst M, Rüedi T (January 1983). "[The "unhappy triad" (UT): slogan or reality in fresh knee injuries?]". Helv Chim Acta (in German). 49 (5): 675–7. PMID 6687587.

- ^ Staron RB, Haramati N, Feldman F, et al. (November 1994). "O'Donoghue's triad: magnetic resonance imaging evidence". Skeletal Radiol. 23 (8): 633–6. doi:10.1007/BF02580384. PMID 7886473. S2CID 19514336.

- ^ Nedeff DD, Bach BR (2001). "Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon autografts: a comprehensive review of contemporary literature". Am J Knee Surg. 14 (4): 243–58. PMID 11703038.

- ^ Alford, J. Winslow; Bernard R. Bach Jr (July 2001). "Managing ACL tears: evaluation and diagnosis". The Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine: 381–390.

- ^ Imaging of Orthopedic Sports Injuries (Medical Radiology / Diagnostic Imaging). Berlin: Springer. 2006. ISBN 3-540-26014-5.

- ^ Johnson, Glen O.; Starkey, Chad (2005). Athletic training and sports medicine. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0-7637-0536-5.

- ^ Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR (January 1997). "Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate-deficient knee: a review of the literature". Am. J. Orthop. 26 (1): 18–23. PMID 9021030.

- ^ "A Complex Injury of the Knee - The Unhappy Triad". Orthopaedic and Spine Center of Newport News. 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2021-07-20.

- ^ Andrade, Renato; Pereira, Rogério; Van Cingel, Robert; Staal, J Bart; Espregueira-Mendes, João (May 2020). "How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) with a focus on quality appraisal (AGREE II)". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 54 (9): 512–519. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100310. PMID 31175108.

- ^ a b Fridén T, Erlandsson T, Zätterström R, Lindstrand A, Moritz U (1995). "Compression or distraction of the anterior cruciate injured knee. Variations in injury pattern in contact sports and downhill skiing". Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 3 (3): 144–7. doi:10.1007/bf01565473. PMID 8821269. S2CID 25692188.

- ^ O'Donoghue D (1950). "Surgical treatment of fresh injuries to the major ligaments of the knee". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 32 (A:4): 721–38. doi:10.2106/00004623-195032040-00001. PMID 14784482.

- ^ O'Donoghue D (1964). "The unhappy triad: Etiology, diagnosis and treatment". Am J Orthop. 6: 242–7 PASSIM. PMID 14237439.

- ^ Pugh D, McKee M (2002). "The "terrible triad" of the elbow". Tech Hand up Extrem Surg. 6 (1): 21–9. doi:10.1097/00130911-200203000-00005. PMID 16520629.

- ^ Simonich S, Wright T (2003). "Terrible triad of the shoulder". J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 12 (6): 566–8. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(03)00216-7. PMID 14671520.