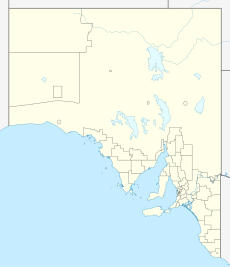

Ooldea, South Australia

| Ooldea South Australia | |

|---|---|

A wood and water train in Ooldea, 1919. | |

| Coordinates | 30°27′33″S 131°50′08″E / 30.459139°S 131.835615°E[1] |

| Location |

|

| LGA(s) | Pastoral Unincorporated Area[1] |

| State electorate(s) | Giles[2] |

| Federal division(s) | Grey[3] |

Ooldea is a tiny settlement in South Australia. It is on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain, 863 km (536 mi) west of Port Augusta on the Trans-Australian Railway. Ooldea is 143 km (89 mi) from the bitumen Eyre Highway.

Being near a permanent waterhole, Ooldea Soak, the area was frequented by Aboriginal peoples, and was the site of a camp for railway construction workers in the early 20th century, and the Ooldea Mission from 1933 to 1952.

History

Ooldea was an important camp during construction of the Trans-Australian Railway, as it is near a permanent clay pan waterhole surrounded by sand dunes, first discovered by Europeans when Ernest Giles used it in 1875. On 17 October 1917, the final link of the railway was completed at Ooldea, linking the western section from Kalgoorlie to the eastern section to Port Augusta.[4] It was around this time that a severe drought[5] led many desert people to migrate closer to the waterhole, increasing pressure on the limited water resources now largely reserved for use by trains.[6] A centenary celebration was held at the siding in 2017.[7]

It was the site of a mission established by the United Aborigines Mission (UAM) in 1933, which later included a children's dormitory housing around 60 children. In 1938 an Aboriginal reserve was created covering the land around the mission.[8] The mission was visited twice by Norman Tindale and was home for many years to Daisy Bates, both concerned with understanding and protecting Aboriginal culture. A cairn commemorating Bates was designed by F. Millward Grey and erected in 1953.[9]

In the 1950s, areas around Maralinga and Emu were used for nuclear testing by the British Government. Around this time the Australian Government resumed much Anangu land to be used for the Woomera Rocket testing Range. Aboriginal people in the area, who were Pila Nguru (Spinifex people, of the Great Victoria Desert) were moved to the Ooldea Mission, which closed in 1952 due to internal divisions in the church. The people did not want to move from there, as they were used to ranging the desert, and had used the Ooldea Soak as a water source for many generations.[10][11]

The people were forcibly moved to a reserve established by the South Australian Government on a former sheep station at Yalata, where Yalata Mission was established by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia. This was an environment quite alien to them, being desert people.[10]

The town was dependent on the Tea and Sugar Train for the delivery of supplies until 1996 when the train was withdrawn. The longest dead straight section of railway line in the world starts west of Ooldea before Watson at the 797 km post and continues to a point between Loongana and Nurina, a distance of 478 km (297 mi).

The historic Ooldea Soak and Former United Aborigines Mission Site and Daisy Bates' Campsite are both listed on the South Australian Heritage Register.[12][13]

References

- ^ a b "Search results for 'Ooldea, LOCU' with the following datasets being selected – 'Suburbs and Localities', 'Local Government Areas', 'SA Government Regions', 'Railways' and 'Gazetteer'". Location SA Map Viewer. Government of South Australia. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ "District of Giles Background Profile". ELECTORAL COMMISSION SA. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Federal electoral division of Grey, boundary gazetted 16 December 2011" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ "The last link". The West Australian. Vol. XXXIII, no. 4, 850. Western Australia. 18 October 1917. p. 4. Retrieved 17 October 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Environment - National Drought 1918 | Australian Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub". knowledge.aidr.org.au. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "'Ooldea Soak description'". www.samuseum.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Paige (17 October 2017). "Celebrating rail's unite nation, 100 years on". The Australian.

- ^ "Ooldea Mission (1933–1952)". Find & Connect. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Memorials To Mrs. Daisy Bates". The Chronicle. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 20 December 1951. p. 33. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ a b Brady, Maggie (1999). "The politics of space and mobility: controlling the Ooldea/Yalata Aborigines, 1952–1982". Aboriginal History. 23. ANU Press: 1–14. ISSN 0314-8769. JSTOR 24046757. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Ooldea Mission (1933–1952)". Find & Connect. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Ooldea Soak and former United Aborigines Mission Site (designated place of archaeological significance)". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 12 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Daisy Bates' Campsite". South Australian Heritage Register. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Retrieved 12 February 2016.[permanent dead link]

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Ooldea, South Australia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ooldea, South Australia at Wikimedia Commons

- Ladd, Mike (March 2020). "The sands of Ooldea" (Audio (4 x 30–40 mins) + text). ABC Radio National. The History Listen.