Ostracod

| Ostracod Temporal range: Ordovician to Recent,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Superclass: | Oligostraca |

| Class: | Ostracoda Latreille, 1802 |

| Subclasses and orders | |

| |

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified,[1] grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typically around 1 mm (0.039 in) in size, but varying from 0.2 to 30 mm (0.008 to 1.181 in) in the case of Gigantocypris. Their bodies are flattened from side to side and protected by a bivalve-like, chitinous or calcareous valve or "shell". The hinge of the two valves is in the upper (dorsal) region of the body. Ostracods are grouped together based on gross morphology. While early work indicated the group may not be monophyletic[2] and early molecular phylogeny was ambiguous on this front,[3] recent combined analyses of molecular and morphological data found support for monophyly in analyses with broadest taxon sampling.[4]

Ecologically, marine ostracods can be part of the zooplankton or (most commonly) are part of the benthos, living on or inside the upper layer of the sea floor. While Myodocopa is restricted to marine environments,[5] the Podocopida are also common in fresh water, and terrestrial species of Mesocypris are known from humid forest soils of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[6] But all three major podocopid lineages, Cypridocopina, Darwinulocopina and Cytherocopina, have several representatives living in terrestrial habitats.[7] They have a wide range of diets, and the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scavengers and filter feeders.

As of 2008, around 2000 species and 200 genera of nonmarine ostracods are found.[8] However, a large portion of diversity is still undescribed, indicated by undocumented diversity hotspots of temporary habitats in Africa and Australia.[9] Of the known specific and generic diversity of nonmarine ostracods, half (1000 species, 100 genera) belongs to one family (of 13 families), Cyprididae.[9] Many Cyprididae occur in temporary water bodies and have drought-resistant eggs, mixed/parthenogenetic reproduction, and the ability to swim. These biological attributes preadapt them to form successful radiations in these habitats.[10]

Etymology

Ostracod comes from the Greek óstrakon meaning shell or tile.

Fossils

Ostracods are "by far the most common arthropods in the fossil record"[11] with fossils being found from the early Ordovician to the present. An outline microfaunal zonal scheme based on both Foraminifera and Ostracoda was compiled by M. B. Hart.[12] Freshwater ostracods have even been found in Baltic amber of Eocene age, having presumably been washed onto trees during floods.[13]

Ostracods have been particularly useful for the biozonation of marine strata on a local or regional scale, and they are invaluable indicators of paleoenvironments because of their widespread occurrence, small size, easily preservable, generally moulted, calcified bivalve carapaces; the valves are a commonly found microfossil.

A find in Queensland, Australia in 2013, announced in May 2014, at the Bicentennary Site in the Riversleigh World Heritage area, revealed both male and female specimens with very well preserved soft tissue. This set the Guinness World Record for the oldest penis.[14] Males had observable sperm that is the oldest yet seen and, when analysed, showed internal structures and has been assessed as being the largest sperm (per body size) of any animal recorded. It was assessed that the fossilisation was achieved within several days, due to phosphorus in the bat droppings of the cave where the ostracods were living.[15]

Description

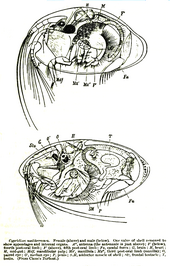

The body of an ostracod is encased by two valves, superficially resembling the shell of a clam. A distinction is made between the valve (hard parts) and the body with its appendages (soft parts).

Body parts

The body consists of a head and thorax, separated by a slight constriction. Unlike many other crustaceans, the body is not clearly divided into segments. The abdomen is regressed or absent, whereas the adult gonads are relatively large.

The head is the largest part of the body, and bears four pairs of appendages. Two pairs of well-developed antennae are used to swim through the water. In addition, there is a pair of mandibles and a pair of maxillae. The thorax has primary three pairs of appendages. The first of these have different functions in different groups. It can be used for feeding (Cypridoidea) or for walking (Cytheroidea), and in some species it has evolved into a male clasping organ. The second pair is mainly used for locomotion, and the third is used for walking or cleaning, but can also be redused or absent. In the Myodocopina it is a multisegmented cleaning organ that resembles a worm. Their external genitals seems to originate from the fusion of three to five appendages. The two "rami", or projections, from the tip of the tail, point downwards and slightly forward from the rear of the shell.[16][17][18]

Podocopa, the largest subclass, have no gills, heart or circulatory system, and blood simply circulates between the valves of the shell. The other subclass of ostracods, the Myodocopa, do have a heart, and the family Cylindroleberididae also have 6-8 lamellar gills. Nitrogenous waste is excreted through glands on the maxillae, antennae, or both.[16][19]

The primary sense of ostracods is likely touch, as they have several sensitive hairs on their bodies and appendages. Compound eyes is only found in Myodocopina within the Myodocopa .[20] All podocopid ostracods have just a naupliar eye, consisting of two lateral ocelli and a single ventral ocellus, but the ventral one is absent in some species.[16][21][22]

Palaeoclimatic reconstruction

A new method is in development called mutual ostracod temperature range (MOTR), similar to the mutual climatic range (MCR) used for beetles, which can be used to infer palaeotemperatures.[23] The ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 (δ18O) and the ratio of magnesium to calcium (Mg/Ca) in the calcite of ostracod valves can be used to infer information about past hydrological regimes, global ice volume and water temperatures.

Ecology

Lifecycle

Male ostracods have two penises, corresponding to two genital openings (gonopores) on the female. The individual sperm are often large, and are coiled up within the testis prior to mating; in some cases, the uncoiled sperm can be up to six times the length of the male ostracod itself. Mating typically occurs during swarming, with large numbers of females swimming to join the males. Some species are partially or wholly parthenogenetic.[16]

In the subclass Myodocopa, all members of the order Myodocopida have brood care, releasing their offspring as first instars, allowing a pelagic lifestyle. In the order Halocyprida the eggs are released directly into the sea, except for a single genus with brood care. In the subclass Podocopa, brood care is only found in Darwinulocopina and some Cytherocopina in the order Podocopida. In the remaining Podocopa it is common to glue the eggs to a firm surface, like vegetation or the substratum. These eggs are often resting eggs, and remain dormant during desiccation and extreme temperatures, only hatching when exposed to more favorable conditions.[24][25] The eggs hatch into nauplius larvae, which already have a hard shell.[16]

Predators

A variety of fauna prey upon ostracods in both aquatic and terrestrial environments. An example of predation in the marine environment is the action of certain Cytherocopina in the cuspidariid clams in detecting ostracods with cilia protruding from inhalant structures, thence drawing the ostracod prey in by a violent suction action.[26] Predation from higher animals also occurs; for example, amphibians such as the rough-skinned newt prey upon certain ostracods.[27]

Bioluminescence

Some ostracods, such as Vargula hilgendorfii, have a light organ in which they produce luminescent chemicals.[28] Most use the light as predation defense, while some, in the Caribbean, use the light for mating. These ostracods are called "blue sand" or "blue tears" and glow blue in the dark. Their bioluminescent properties made them valuable to the Japanese during World War II, when the Japanese army collected large amounts from the ocean to use as a convenient light for reading maps and other papers at night. The light from these ostracods, called umihotaru in Japanese, was sufficient to read by but not bright enough to give away troops' position to enemies.[29]

See also

- Mari Mari Group, fossil formation in the state of Amazonas of northwestern Brazil

References

- ^ Richard C. Brusca & Gary J. Brusca (2003). Invertebrates (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-097-5.

- ^ Richard A. Fortey & Richard H. Thomas (1998). Arthropod Relationships. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-75420-3.

- ^ S. Yamaguchi & K. Endo (2003). "Molecular phylogeny of Ostracoda (Crustacea) inferred from 18S ribosomal DNA sequences: implication for its origin and diversification". Marine Biology. 143 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1062-3. S2CID 83831572.

- ^ Zaharoff, Alexander K.; Lindgren, Annie R.; Wolfe, Joanna M.; Oakley, Todd H. (2013-01-01). "Phylotranscriptomics to Bring the Understudied into the Fold: Monophyletic Ostracoda, Fossil Placement, and Pancrustacean Phylogeny". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (1): 215–233. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss216. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 22977117.

- ^ News from mid-Cretaceous 'Burmese Amber'

- ^ J. D. Stout (1963). "The Terrestrial Plankton". Tuatara. 11 (2): 57–65.

- ^ Austromesocypris bluffensis sp. n. (Crustacea, Ostracoda, Cypridoidea, Scottiinae) from subterranean aquatic habitats in Tasmania, with a key to world species of the subfamily

- ^ K. Martens; I. Schon; C. Meisch; D. J. Horne (2008). "Global diversity of ostracods (Ostracoda, Crustacea) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 185–193. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9245-4. S2CID 207150861.

- ^ a b K. Martens, S. A. Halse & I. Schon (2012). "Nine new species of Bennelongia De Deckker & McKenzie, 1981 (Crustacea, Ostracoda) from Western Australia, with the description of a new subfamily". European Journal of Taxonomy. 8: 1–56.

- ^ Horne, D. J.; Martens, Koen (1998). "An assessment of the importance of resting eggs for the evolutionary success of non-marine Ostracoda (Crustacea)". In Brendonck, L.; De Meester, L.; Hairston, N. (eds.). Evolutionary and ecological aspects of crustacean diapause. Vol. 52. Advances in Limnology. pp. 549–561. ISBN 9783510470549.

- ^ David J. Siveter; Derek E. G. Briggs; Derek J. Siveter; Mark D. Sutton (2010). "An exceptionally preserved myodocopid ostracod from the Silurian of Herefordshire, UK". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1687): 1539–1544. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.2122. PMC 2871837. PMID 20106847.

- ^ Malcolm B. Hart (1972). R. Casey; P. F. Rawson (eds.). "A correlation of the macrofaunal and microfaunal zonations of the Gault Clay in southeast England". Geological Journal (Special Issue 5): 267–288.

- ^ Noriyuki Ikeya, Akira Tsukagoshi & David J. Horne (2005). Noriyuki Ikeya; Akira Tsukagoshi & David J. Horne (eds.). "Preface: The phylogeny, fossil record and ecological diversity of ostracod crustaceans". Hydrobiologia. 538 (1–3): vii–xiii. doi:10.1007/s10750-004-4914-z. S2CID 43836792.

- ^ Oldest penis:

The oldest fossilised penis discovered to date dates back around 100 million years. It belongs to a crustacean called an ostracod, discovered in Brazil and measuring just 1mm across. - ^ World's oldest sperm 'preserved in bat poo', Anna Salleh, ABC Online Science, 14 May 2014, accessed 15 May 2014

- ^ a b c d e Robert D. Barnes (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 680–683. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ Ostracoda - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

- ^ Recent Freshwater Ostracods of the World: Crustacea, Ostracoda, Podocopida

- ^ The early life history of tissue oxygenation in crustaceans: the strategy of the myodocopid ostracod Cylindroleberis mariae

- ^ Molecular phylogenetic evidence for the independent evolutionary origin of an arthropod compound eye - NCBI

- ^ Functional morphology and light-gathering ability of podocopid ostracod eyes and the palaeontological implications

- ^ A gigantic marine ostracod (Crustacea: Myodocopa) trapped in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber

- ^ D. J. Horne (2007). "A mutual temperature range method for European Quaternary nonmarine Ostracoda" (PDF). Geophysical Research Abstracts. 9: 00093.

- ^ Field Guide to Freshwater Invertebrates of North America

- ^ Recent Freshwater Ostracods of the World: Crustacea, Ostracoda, Podocopida

- ^ John D. Gage & Paul A. Tyler (1992-09-28). Deep-Sea Biology: A Natural History of Organisms at the Deep-Sea Floor. University of Southampton. ISBN 978-0-521-33665-9.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan (2008). "Rough-skinned Newt ("Taricha granulosa")". Globaltwitcher, ed. N. Stromberg. Archived from the original on 2009-05-27.

- ^ Osamu Shimomura (2006). "The ostracod Cypridina (Vargula) and other luminous crustaceans". Bioluminescence: Chemical Principles and Methods. World Scientific. pp. 47–89. ISBN 978-981-256-801-4.

- ^ Jabr, Ferris. "The Secret History of Bioluminescence". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

External links

- Kempf Database Ostracoda

- Ostracoda fact sheet, Guide to the Marine Zooplankton of South-eastern Australia]

- Key to the two subclasses

- International Research Group on Ostracoda

- Ostracoda Fact Sheet

- Huge sperm of ancient crustaceans

- World Ostracoda Database