Parviz Rustambeyov

Parviz Rustambeyov Pərviz Rüstəmbəyov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | 1922-01-07 Baku, Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic |

| Died | 1949-12-29 (aged 27) Baku, Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic |

| Genres | jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Saxophonist |

| Instrument(s) | Saxophone |

| Years active | 1940-1949 |

Parviz Rustambeyov was Azerbaijan-born saxophonist and jazz musician who fell victim to Soviet repressions.

Life[edit]

Parviz Rustambeyov, the son of Ismayil was born on January 7, 1922, in Baku.[1] He attended a music circle at the Pioneers' Palace, where he played the clarinet. At the age of 18, in 1940, Tofig Guliyev invited him to perform in the orchestra at the "Senetkarlıg" cinema.[2]

After the start of World War II, the young performers of the orchestra continued their activities within the military division. They were sent to the 402nd artillery division stationed in Nakhchivan. By the end of 1942, after the disbandment of the orchestra, Parviz Rustambeyov was assigned to the Aviation Jazz under the leadership of A.V. Shustapalov. However, due to illness, he was discharged from there in July 1943.[1]

In 1944, the renowned jazz orchestra led by Eddy Rosner came to Baku for a concert. Impressed by Parviz Rustambeyov's performance, Rosner invited him to join his orchestra as the first saxophonist and clarinetist.[3] Parviz accepted the invitation and started performing with Rosner's orchestra. He lived in Moscow for a while during this period and was also invited by Leonid Utyosov to join his ensemble.[4]

Parviz was invited on stage to perform with the jazz orchestra while dining at the "Metropol" restaurant in Moscow with his friends. His rendition of American classics caught the interest of the Americans at the restaurant. After his performance, they approached Parviz, inviting him to the United States to gain experience in the homeland of jazz. He went to the US Embassy upon their invitation, seeking to meet the cultural attaché, but couldn't locate them and returned without success.[4] As he left the embassy, two plainclothes agents from the State Security Committee (DTK) approached him, inquiring about his visit to the embassy. Parviz explained the purpose of his visit. Later, he felt he was being followed and sought advice from Tofig Guliyev, who was in Moscow at that time. Tofig Guliyev provided him with money to purchase an urgent ticket back to Baku.[4]

After returning to Baku, he decided to form his own orchestra. Initially, he started performing with his orchestra at the 'Red East' and later at the 'Artist' cinema. However, in January 1949, he was dismissed from his job, accused of 'Western decadence”.[5]

After being dismissed from work, he struggled to find employment for a while. Later, he secured a job at a small restaurant near the railway station. However, on May 20, 1949, Parviz Rustambeyov was arrested upon the orders of Ayriyan, the military prosecutor of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Azerbaijan SSR. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison.[5]

Rustambeyov is an anti-Soviet and pro-American individual. He praises the American lifestyle, household, and art, criticizes Soviet realities, and maintains connections with foreigners. He intends to illegally flee abroad.[4]

On December 29, 1949, at 3:50 a.m., detainee Parviz Rustambeyov passed away in the internal detention facility of the Azerbaijani Ministry of Internal Affairs under suspicious circumstances.[1]

In 1957, due to complaints from the musician's mother, Munavvar Khanim, the Republic Prosecutor's Office appealed to the investigative committee for clarification regarding Parviz Rustambeyov's case.[5] On January 6, 1958, the criminal case against Parviz Rustambeyov was terminated due to inconsistencies in the evidence, and the case was closed.[6]

Family[edit]

Parviz Rustambeyov's grandfather, Asad bey, lived in Salyan and was a landowner. Among Asad bey's four sons, one of them, Mammad, passed away at the age of 19. The other three sons, Fetulla, Bakhısh, and Shahbaz, received higher education in St. Petersburg. Since Bakhısh didn't have any children of his own, he took in Ismayıl, the orphaned son of his deceased brother Mammad.[1] Ismayıl Rustambeyov married Munavvar Khanim and had children, including Parviz Rustambeyov and Farida Rustambeyova. Ismayıl Rustambeyov passed away due to tuberculosis in 1942.[1]

Parviz Rustambeyov married a woman named Taisiya Mikhaylovna Stepanova in April 1941. They had a son together. They named the child Adil in honor of composer Tofig Guliyev's brother and their friend, Adil. Unfortunately, the child passed away at a year and a half old.[1] After divorcing Taisiya, Parviz married again in 1943. In 1945, they had another child.[7]

Memory[edit]

In 2002, the film "Vaxtın o Üzündə" (On the Face of Time) dedicated to the musician's life was produced on Lider TV, with screenplay by Nariman Abdulrahmanlı and directed by Akif Arifoghlu.[8]

In 2016, the artist Vuqar Ali painted portraits of Azerbaijani and foreign jazz musicians, including Parviz Rustambeyov.[9] These artworks were showcased in a solo exhibition during the International Jazz Festival held in Baku.[10]

On December 22, 2017, the film "Ölümündən sonra məhkəmə" (Court after His Death) about Parviz Rustambeyov's life was presented at the Gara Garayev Central Music School by ARB Aran Film Creative Center. The film is a docudrama that uses archival materials and information from the criminal case of Parviz Rustambeyov.[11] The screenplay was by Yegane Abdulmammedova, who also directed the film.[12]

On April 10, 2022, within the "Qətl planı" (Assassination Plan) project aired on Azerbaijan Television, a film directed by Elnur Aliyev, who also wrote the screenplay, was produced about the murder of Parviz Rustambeyov.[13]

Photos[edit]

-

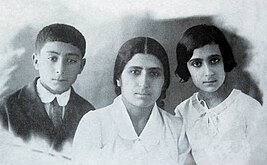

Together with his mother Munavvar and sister Farida

-

Together with his wife Taisya and son Adil

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Şahanə Rəhimli (2017-05-18). "Azərbaycan cazının erməni əli ilə KQB-də məhv edilən əfsanəsi" (in Azerbaijani). azvision.az. Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Olqa Bulanova (2019-05-07). "Saksafonda caz ifa etdiyi üçün 27 yaşında güllələnən əfsanəvi cazmen – Pərviz Rüstəmbəyov" (in Azerbaijani). edebiyyat.az. Archived from the original on 2021-10-17. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Həbsdə sabun yeyib intihar edən azərbaycanlı musiqiçi" (in Azerbaijani). milli.az. 2017-12-26. Archived from the original on 2017-12-26. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ a b c d Olqa Bulanova (26 March 2018). "Звезда и смерть легендарного джазмена Парвиза Рустамбекова" (in Russian). azerhistory.com. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ a b c "Рустамбеков Парвиз (Пиро) – джазовый музыкант, репрессирован" (in Russian). ourbaku.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Lalə Azəri (2012-02-10). "Caz musiqisinin improvizatoru" (in Azerbaijani). medeniyyet.az. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Bu gün tanınmış saksafonçu, cazmen Pərviz Rüstəmbəyovun anım günüdür" (in Azerbaijani). baku-art.com. 2022-12-28. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Nəriman Əbdülrəhmanlı (2002). Vaxtın o Üzündə (Televiziya filmi). Bakı: Lider TV. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Rüstəm Qasımov (2016-10-31). "Вугар Али: "Живопись и джаз - два искусства импровизации"" (in Russian). ann.az. Archived from the original on 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ "Vüqar Əlinin "Rənglərin ritmi" adlı fərdi sərgisi" (in Azerbaijani). culture.gov.az. 2019-09-19. Archived from the original on 2022-08-17. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Xəzər Süleymanlı (2017-12-17). "Əfsanəvi azərbaycanlı cazmenә - Ölümündən sonra məhkəmə" (in Azerbaijani). teleqraf.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ ""Ölümündən sonra məhkəmə" filmi təqdim olunacaq" (in Azerbaijani). 525-ci qəzet. 2017-12-17. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ^ Elnur Əliyev (2022). Pərviz Rüstəmbəyovun qətli "Qətl planı"nda (Televiziya filmi). Bakı: AzTV. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-01-16.