Precarious work

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (February 2015) |

- For the general condition, global perspectives, see Precarity.

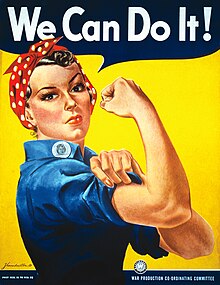

Precarious work is non-standard employment that is poorly paid, insecure, unprotected, and cannot support a household.[1] In recent decades there has been a dramatic increase in precarious work due to such factors as globalization, the shift from the manufacturing sector to the service sector, and the spread of information technology.[1] These changes have created a new economy which demands flexibility in the workplace and, as a result, caused the decline of the standard employment relationship and a dramatic increase in precarious work.[1] An important aspect of precarious work is its gendered nature, as women are continuously over-represented in this type of work.[1]

Contrast with regular employment

Precarious work is frequently associated with the following types of employment: "part-time employment, self-employment, fixed-term work, temporary work, on-call work, home-based workers, and telecommuting."[1][2] All of these forms of employment are related in that they depart from the standard employment relationship (full-time, continuous work with one employer).[1]

The standard employment relationship can be defined as full-time, continuous employment where the employee works on his employer’s premises or under the employer's supervision.[1] The central aspects of this relationship include an employment contract of indefinite duration, standardized working hours/weeks and sufficient social benefits.[1] Benefits like pensions, unemployment, and extensive medical coverage protected the standard employee from unacceptable practices and working conditions.[1] The standard employment relationship emerged after World War II with the men who worked in the manufacturing industries and this soon became the norm.[1] On completing their education, most men would go on to work full-time for one employer their entire lives until their retirement at the age of 65.[1] During this time, women would only work temporarily until they got married and had children, at which time they would withdraw from the workforce.[1]

The regulation of precarious work

Globalization and the spread of information technology have created a new economy that emphasizes flexibility in the marketplace and in employment relationships.[1] These influences have resulted in the increase of women in the workplace as well as the rise in precarious work.[1] Regulation of precarious work differs between each country.[1] These regulations can either reinforce the differences between standard and precarious employment or they can serve to lessen these differences by increasing the protections afforded to precarious workers.[1]

Changes in the nature of work in developing and developed countries have inspired the International Labour Organization (ILO) to develop standards for atypical and precarious employment.[3] The ILO began to expand its policies to include precarious workers with the Convention Concerning Part-time Work in 1994 and the Convention Concerning Home Work in 1996.[3] While, the Organization’s more recent initiative, titled "Decent Work," began in 1999 and attempts to improve the conditions of all people- waged, unwaged, those in the formal and informal market, by enlarging labor and social protections.[3]

There is also an increasing interest in research on young adults and the consequences of precarious work.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Fudge, Judy; Owens, Rosemary (2006). "Precarious work, women and the new economy: the challenge to legal norms". In Fudge, Judy; Owens, Rosemary (eds.). Precarious work, women and the new economy: the challenge to legal norms. Onati International Series in Law and Society. Oxford: Hart Publishing. pp. 3–28. ISBN 9781841136165.

- ^ International Monetary Fund, Central Committee 2007 (2007). "Global action against precarious work". Metal World (1). Global Union Research Network - GURN: 18–21. Archived from the original on 2014-06-10.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Vosko, Leah F. (2006). "Gender, precarious work, and the international labour code: the ghost in the ILO closet". In Fudge, Judy; Owens, Rosemary (eds.). Precarious work, women and the new economy: the challenge to legal norms. Onati International Series in Law and Society. Oxford: Hart Publishing. pp. 53–76. ISBN 9781841136165.

- ^ http://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4835&context=utk_gradthes

Further reading

- Andranik S. Tangian "Is flexible work precarious? A study based on the 4th European survey of working conditions 2005", WSI-Diskussionspapier Nr. 153, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung June 2007

- Arne L. Kalleberg (2011). Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-1-61044-747-8.

- Sonia McKay, Steve Jefferys, Anna Paraksevopoulou, Janoj Keles, "Study on Precarious work and social rights" Working Lives Research Institute, London Metropolitan University, April 2012