Rahmah el Yunusiyah

Rahmah el Yunusiyah | |

|---|---|

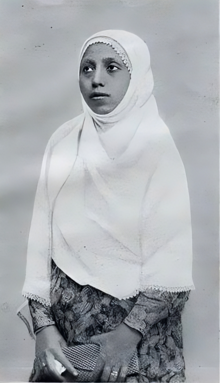

el Yunusiyah in 1932 | |

| Born | 26 October 1900 Nagari Bukit Surungan, Padang Panjang, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 26 February 1969 (aged 68) Padang Panjang, West Sumatra, Indonesia |

| Nationality | Indonesian |

| Title | MP of the People's Representative Council |

| Term | 1956–1959 |

| Political party | Masyumi |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Rahmah el Yunusiyah (Van Ophuijsen Spelling Rahmah el Joenoesijah, 26 October 1900 – 26 February 1969) was a Dutch East Indies and Indonesian politician, educator, and activist for women's education. Born into a prominent family of Islamic scholars, she was made to leave school in order to get married as a teenager. After a few years of marriage, el Yunusiyah obtained a divorce and returned to her education.

In 1923, she founded Diniyah Putri, the first known Islamic school (madrasa) for girls in the Indies. As the school grew and established itself, el Yunusiyah helped found three more schools for women and girls as well as a teacher training institute. An Islamic nationalist, el Yunusiyah was imprisoned by the Dutch authorities before Indonesia's independence. In 1955 she became one of the first women to be elected to the People's Consultative Assembly of independent Indonesia as a member of the Masyumi Party. She died aged 68 in 1969 in her hometown, Padang Panjang.

Early life

[edit]El Yunusiyah was born on 26 October 1900 in Bukit Surungan, Padang Panjang, West Sumatra, Dutch East Indies.[1][2] She was the youngest child of an elite Minangkabau family which belonged to the ulama; her father was a well-known qadi named Muhammad Yunis bin Imanuddin and her mother was named Rafi'ah.[1][3][4] Her grandfather, Sheikh Imaduddin, was also a well-known Islamic scholar, astronomer and leader of the local branch of the Naqshbandi order.[5] Although she started to get basic Islamic tutoring from her father, he died when she was only six years old.[6][7] After that she began to receive an education from some of her father's former students, and learned to read and write.[a][1][7] She also received some training in midwifery at a local hospital.[4]

Marriage

[edit]Her family arranged for her to be married to a scholar named Bahauddin Lathif in 1916, while she was still a student in Padang Panjang, and she was required to leave school.[1][8] However, she continued to study Islam in private study circles starting in 1918.[9] In 1922, her husband married two more wives, and el Yunusiyah obtained a divorce before returning to her education; they had not had any children during their marriage.[1][10]

Educational activism and leadership

[edit]El Yunusiyah's family had long been involved in Islamic education in West Sumatra, and in 1915 her brother Zainuddin Labay el Yunusi had founded the Dinayah School; Rahmah became a student there.[1] After returning to study there when her marriage ended in 1922, she led study sessions among the girls outside of class.[1] This study circle was influenced by Ruhana Kuddus's Amai Setia; it was called the Women and Girl's Association.[b][11]

Diniyah Putri

[edit]El Yunusiyah was unsatisfied with the level of Islamic education for girls in the schools they had access to, as well as the social dynamics that prevented them from fully accessing education in mixed-gender schools. She consulted with local ulema, and with the support of her brother Zainuddin and her study circle, opened a school specifically for girls in November 1923.[1][8] This school, located in Padang Panjang, was called Diniyah School Putri;[c] it is generally thought to be the first Muslim religious school in the country for young girls.[1][12]

At first, the school did not have its own building and operated out of a mosque, where she was the main teacher.[1][12] The initial cohort of students consisted of 71 women, mostly young housewives from the surrounding area; the curriculum consisted of basic Islamic education, Arabic grammar, some modern European schooling, and handicrafts.[12][13] The existence of a modern school for girls was not fully accepted in the community, and she faced some hostility and criticism.[7][14] El Yunusiyah, a deeply religious woman, believed that Islam demanded a central role for women and women's education.[9][15]

In 1924, a permanent classroom for the school was built in a local house.[12] The same year, her brother Zainuddin died; despite fears that the loss of his sponsorship would mean the end of the school, el Yunusiyah continued her efforts.[4] El Yunusiyah also started a supplemental program for older women who had not had proper educations, although it was cut short after the 1926 Padang Panjang earthquakes destroyed the Diniyah school building.[1] The classes met in makeshift buildings for several years and Muhammadiyah approached her with an offer to take over the operation of the school and help to reestablish it; she decided not to accept the offer.[8] She toured widely in the Indies to raise money and a new permanent building was built and opened in 1928.[6] The nationalist figure Rasuna Said had been a student in the mixed gender Dinayah school, becoming an assistant teacher in the girls' school in 1923. Said incorporated politics explicitly into her courses, causing a disagreement with el Yunusiyah. Said left the school for Padang in 1930.[13]

The school continued to gain popularity and by the end of the 1930s had as many as five hundred students.[8][16][17] The scholar Audrey Kahin calls Diniyah Putri "one of the most successful and influential of the schools for women" in pre-independence Indonesia.[18]

Continued advocacy

[edit]El Yunusiyah disdained contact with the Dutch; unlike other modernizing female figures such as Kartini, she did not have European friends and in turn did not have a high profile among them.[19] She purposefully did not accept government subsidies for her schools, and despite incorporating some elements of European-style schooling, the dress, calendar cycle and curriculum were focused squarely on Islam.[16] Like the Taman Siswa movement of independent schools, she fought hard to avoid being penalized by Dutch regulations against so-called "wild" or illegal schools.[8]

During the 1930s, el Yunusiyah continued to develop the capacity of Islamic women's education in West Sumatra and continued her support for the Indonesian nationalist movement despite its criminalization by the Dutch. In 1933 she established an association of female teachers of Islam, and in 1934 she held a meeting to sign women up for the Indonesian cause.[19][20] She became involved in the Persatuan Muslim Indonesia, an Indonesian nationalist movement with an Islamic character.[2] During this time she was fined by the Dutch for discussing politics[d] in illegal meetings.[2][8] In 1935, el Yunusiyah founded two additional schools in Jakarta, as well as a high school in Padang Panjang in 1938.[10] She also founded a teacher training institute in 1937, the Kulliyatul Muallimat al Islamiyyah (KMI).[1][8]

World War II and independence era

[edit]During the Japanese occupation of West Sumatra, el Yunusiyah collaborated with the Japanese and led a Giyūgun unit in Padang Panjang. However, she opposed the Japanese use of Indonesians as comfort women and campaigned against the practice.[8][9] During the war, she also made efforts to materially support her former students.[8] In 1945, upon hearing of the proclamation of Indonesian independence, she immediately raised the red-and-white Indonesian flag in the schoolyard at Diniyah Putri.[9] After the end of the war, during the Indonesian Revolution, she set up a supply unit to support the Republican side against the Dutch. She was held prisoner by the Dutch authorities for seven months in 1949, and was released after the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference.[7][10]

Politics

[edit]

El Yunusiyah was recruited to participate in the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence.[8] The new Indonesian Republic brought about a complete revolution in education in the country, and she participated in some of the first major conferences about updating the education system in late 1949.[6]

In 1955, el Yunusiyah was elected to the first Indonesian People's Consultative Assembly, one of the first female members of the legislature.[6][10][21] She was sworn in in late March 1956.[22] She was elected representing the Islam-oriented Masyumi Party, of which she had been an early supporter in West Sumatra.[2][23] In late 1956 she also became an advisor to the Banteng Council under Lt. Col. Ahmad Husein.[24] Husein's organization was a local movement against the central government; the council enjoyed broad support in West Sumatra.[25]

In 1958, she came to support the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI), an anti-government movement largely based in Sumatra.[8] Her support of that movement deepened her schism with her former colleague Rasuna Said, who was now closely allied with Sukarno.[26] Because of her support for the PRRI, el Yunusiyah lost her seat in the Assembly.[7][8] She was arrested in 1961 but was later freed under an amnesty granted to former PRRI militants by Sukarno.[8]

Education

[edit]In 1950 el Yunusiyah returned to Padang Panjang to supervise the Diniyah Putri school, which was once again in operation after the war.[6] In 1956, Abd al-Rahman Taj, the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar University in Egypt, visited el Yunusiyah's school in Padang Panjang. Taj was impressed, and in 1957, el Yunusiyah was invited to visit Al-Azhar, shortly after she had completed her hajj to Mecca.[27] The faculty of Al-Azhar awarded her the title of Syeikah, which they had never given to a woman before.[9] Subsequently, graduates of Diniyah Putri were granted scholarships to continue their studies at Al-Azhar by the Egyptian authorities.[27] In the 1960s, following her political career, el Yunusiyah returned to her educational activism and pushed for the founding of an Islamic university specifically for women.[2] In 1967, her efforts succeeded, and a women's university was inaugurated by West Sumatra governor Harun Zain.[2]

She died on 26 February 1969, in Padang Panjang.[2][6] Her grave, located on the grounds of the Diniyah Putri school dormitory, is listed as a cultural heritage site by the West Sumatra Cultural Conservation organization.[2]

Notes

[edit]- ^ el Yunusiyah learned Arabic and Latin scripts (most likely the Arabic language as well as the Jawi alphabet and Van Ophuijsen Spelling System for local languages)

- ^ Dutch: Vrouwenbond dan Meisyeskring, Indonesian: Perkumpulan Wanita dan Kelompok Gadis.

- ^ Also known as Madrasah Diniyah Li al-Banat.

- ^ Specifically, the "wild schools" ordinance.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Munawaroh, Unaidatul (2002). "Rahmah el-Yunusiah: Pelopor Pendidikan Perempuan". In Burhanuddin, Jajat (ed.). Ulama perempuan Indonesia (in Indonesian). Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 1–38. ISBN 9789796866441.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Rahmah El Yunusiyah". Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Sumatera Barat (in Indonesian). Sekretariat Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan. 5 June 2018. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Iris Busschers; Kirsten Kamphuis; David Kloos (2020). "Teachers, missionaries, and activists. Female religious leadership and social mobility in Southeast Asia, 1920s-1960s". International Institute for Asian Studies (85). Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ a b c Gatra. "Special Report: Perguruan Diniyyah Puteri". Gatra. Archived from the original on 2017-01-03. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ "Mengenal Rahmah El-Yunusiah, Ulama dan Pejuang Pendidikan Perempuan di Indonesia". Kompas (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Muhammad, Husein (2020). Perempuan ulama di atas panggung sejarah (Cetakan pertama ed.). Baturetno, Banguntapan, Yogyakarta. pp. 166–70. ISBN 9786236699003.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Zuraya, Nidia (7 April 2012). "Rahmah El-Yunusiyah: Perintis Sekolah Wanita Islam di Indonesia". Republika Online (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Raditya, Iswara. "Rahmah El Yunusiyah Memperjuangkan Kesetaraan Muslimah". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Rahmah el Yunusiyyah Pejuang Pendidikan Kaum Wanita". Jejak Islam untuk Bangsa. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Vreede-De Stuers, Cora (1960). The Indonesian Woman: Struggles and Achievements. Gravenhage: Mouton & Co. p. 183. ISBN 9789027910448.

- ^ Ohorella, G. A.; Sutjiatiningsih, Sri; Ibrahim, Muchtaruddin (1992). Peranan wanita Indonesia dalam masa Pengerakan Nasional (in Indonesian). Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional. p. 9. Archived from the original on 2022-07-01. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ a b c d Seno, Seno (2010). Peran kaum mudo dalam pembaharuan pendidikan Islam di Minangkabau 1803-1942. Padang: BPSNT Padang Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-602-8742-16-0. Archived from the original on 2022-07-01. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ a b Hadler, Jeffrey (2013). "7. Families in Motion". Muslims and Matriarchs: Cultural Resilience in Indonesia through Jihad and Colonialism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 156–76. doi:10.7591/9780801461606-009. ISBN 978-0-8014-6160-6. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- ^ Karim, Wazir Jahan B. (2021). "In Body and Spirit: Redefining Gender Complementarity in Muslim Southeast Asia". In Ibrahim, Zawawi; Richards, Gareth; King, Victor T. (eds.). Discourses, Agency and Identity in Malaysia: Critical Perspectives. Springer Nature. p. 113. ISBN 9789813345683.

- ^ Doorn-Harder, Nelly van (2006). Women shaping Islam : Indonesian women reading the Qurʼan. Urbana. p. 173. ISBN 9780252030772.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Johns, A. H. (1989). "7. Islam in Southeast Asia". In Kitagawa, Joseph M. (ed.). The Religious traditions of Asia. New York: Macmillan Pub. Co. p. 175. ISBN 9780028972114.

- ^ Srimulyani, Eka (2012). Women from Traditional Islamic Educational Institutions in Indonesia : Negotiating Public Spaces. Amsterdam University Press. hdl:20.500.12657/34531. ISBN 978-90-8964-421-3. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ^ Kahin, Audrey (2015). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 505. ISBN 9780810874565.

- ^ a b Gelman Taylor, Jean (2017). "10. Breaking Dependence on Foreign Powers". Indonesia. Yale University Press. p. 297. doi:10.12987/9780300128086-014. ISBN 978-0-300-12808-6. S2CID 246152772. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- ^ "Vrouwenbeweging in Indonesië". De tribune: soc. dem. weekblad (in Dutch). Amsterdam. 5 July 1934. p. 6. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Hasil Rakjat Memilih Tokoh-tokoh Parlemen (Hasil Pemilihan Umum Pertama - 1955) di Republik Indonesia (in Indonesian). 1956. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ "Beëdiging van nieuwe parlementsleden". De nieuwsgier (in Dutch). Batavia [Jakarta]. 28 March 1956. p. 1. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Asnan, Gusti (2007). Memikir ulang regionalisme : Sumatera Barat tahun 1950-an (in Indonesian) (1 ed.). Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 81. ISBN 9789794616406.

- ^ "Banteng-raad". De nieuwsgier (in Dutch). Batavia [Jakarta]. 24 December 1956. p. 2. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Zed, Mestika (2001). Ahmad Husein: perlawanan seorang pejuang (in Indonesian) (1 ed.). Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan. p. 173. ISBN 9789794167212.

- ^ Ting, Helen; Blackburn, Susan, eds. (2013). Women in Southeast Asian nationalist movements : a biographical approach. Singapore: NUS Press. p. 117. ISBN 9789971696740.

- ^ a b Salim HS, Hairus (2012). "Indonesian Muslims and cultural networks". In Lindsay, Jennifer; Sutedja-LIem, M. H. T. (eds.). Heirs to world culture : Being Indonesian, 1950-1965. Leiden, NLD: Brill. p. 83. ISBN 978-90-04-25351-3. OCLC 958572352. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-01.