Repudiation of debt at the Russian Revolution

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (April 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

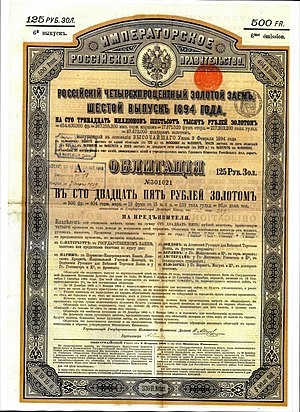

Russian bonds of 1894 |

The repudiation of debt at the Russian revolution was the 1918 rejection of all sovereign debt and other financial obligations by the Bolshevik government upon attaining power.

In February 1918, after the Russian Revolution, the repudiation of the debt by the Soviet government shocked international finance and triggered unanimous condemnation by the governments of the great powers. The British, and especially the French, had lost millions of pounds of foreign investment in Russia.

Revolutionary Russia completely fell out of the world economy and sealed itself up in isolation, which would not be disturbed until the hostilities with other nations during the Second World War.[1]

From Tsarist Russia to the 1917 revolution

The Russian Empire

In the early 19th century, the Russian Empire turned to the public capital markets and, especially, foreign markets and foreign intermediaries, to regulate and stimulate the growth of its economy, financing its ambition and its development. The transformation from a feudal to a capitalist system proceeded little by little and required foreign investment. Until then, the Russian economy was mainly dominated by agricultural and local production and thus did not stimulate the creation of a national marketplace. Borrowing by the Russian government was important for both European and Russian domestic financial markets. It was the government's need to finance its budget deficit that stimulated the progress of the Russian financial system.

In 1913, foreign investors held 49.7% of Russian government debt and owned nearly 100% of all petroleum fields, 90% of mines, 50% of chemicals and 40% of metallurgical industries. This amounted to the largest foreign debt in the world at the time. France was the major lender to Russia and French investors financed the creation of iron and steel industries and mining operations. In 1914, 80% of the Russian government debt was held in France and 14% in Great Britain.[2]

World War I

Russia entered World War I in July 1914. Germany, France, Great Britain and Tsarist Russia had been preparing for war for a long time. Military spending was enormous and financially catastrophic for the Russian government.

Between the beginning of the war and Bolsheviks’ accession to power, the debt soared to £3,385 million, about 3.5 times what it had been. Furthermore, the First World War caused 3,300,000 deaths in Russia between 1914 and February 1917: 1,800,000 soldiers and 1,500,000 civilians. Thus, the burden of the war finally caused a complete collapse of the economy and a change in the political system.

The Russian Revolutions

On February 17, 1917, the Tsar Nicholas II, the last Emperor of Russia, was forced to sign his abdication and the end of the Russian Imperial Government and of the Romanov dynasty. The new government decided to continue the war, which meant more military spending. To increase budget revenues, a state monopoly was introduced on the sales of sugar, tea, matches, tobacco, and other consumer products. Still, the printing press remained the main source of revenues. This was a period of hyperinflation.

Bolshevik revolutionaries overthrew the Provisional government on October 24, 1917, subsequently creating the Soviet government. The amounts of payments in default were enormous.[3] Russian debt to Great Britain alone at the end of World War I was estimated at between 538 and 568 million pounds. The amount of debt to France was estimated at 3,573 million francs and Russian foreign debt to Japan equaled 147 million dollars.

The debt repudiation

On February 8, 1918, the Soviet government repudiated all bonds issued by the Tsarist government when the Soviet of People's Commissars of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) cancelled all previously issued Russian government debt. It stopped payment on foreign debt at the beginning of 1918 and declared that all debts contracted by the Russian Empire were cancelled, as well as the debts contracted by the Russian Provisional Government, so that the war could be continued from February to November 1917.

At the same time, the Soviets decided to expropriate all assets of foreign nations in Russia. The Soviets also nationalized banks, lands, and industries. By repudiating the external debt, the Soviet government implemented the Petrograd Soviet’s decision of 1905.[4]

Reaction of creditors

The cancellation of the foreign debt by the Soviet Russia stunned international finance and triggered universal denunciation by the allied powers.[5] Western governments were convinced that they should openly support the anti-Bolshevik forces to restore a capitalist order.

Even in 1924, after the Russian Civil War was over, The Investor's Monthly Manual in London published quotes for Russian bonds.

Modern day

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly formed Russian Federation had to not only come up with a new financial strategy for its future, but also had to consider repaying the billions of dollars the Soviet Union borrowed from abroad. In 1996, Paris and Moscow signed an accord for Russia to repay a nominal value of between $80 and $100 for each of the 4 million czarist bonds believed to remain in circulation in France, for a total payout of around $400 million.[6] Russia paid but not nearly as generously as the descendants of French bond buyers hoped.[7]

References

- ^ Tomáš Evan (2014).Chapters of European Economic History, p. 61.

- ^ Harold G. Moulton & Leo Pasvolsky. Russian Debts and Russian Reconstruction. 1924, p. 21

- ^ Kim Oosterlinck. Hope Springs Eternal: French Bondholders and the Repudiation of Russian Sovereign debt Yale University Press. 2016

- ^ Toussaint, Eric. Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt.

- ^ New York Times - 11 June 1920 FRANCE WANTS GOLD OF SOVIETS SEIZED

- ^ Chicago Tribune - 28 November 1996 Russia To Pay Off Old Bonds

- ^ Russia Beyond - 15 January 2018 French still waiting for multi-million imperial debt payout from Moscow