Sakyong Mipham

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | Ösel Rangdrol Mukpo November 15, 1962 Bodh Gaya, India |

| Religion | Kagyü and Nyingma |

| Nationality | American, Tibetan |

| Spouse | Khandro Tseyang Ripa Mukpo |

| Children | 3 daughters |

| School | Shambhala Buddhist |

| Lineage | Chogyam Trungpa |

| Senior posting | |

| Reincarnation | Mipham the Great |

| Sakyong Mipham | |||||

| Tibetan name | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan | ས་སྐྱོང་མི་ཕམ་ | ||||

| |||||

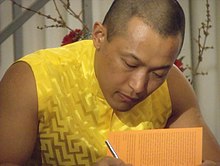

Sakyong Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche, Jampal Trinley Dradul (born Ösel Rangdrol Mukpo on November 15, 1962) is an American and Tibetan Buddhist descendant of the Shambhala lineage and Shambhala, a worldwide network of urban Buddhist meditation centers, retreat centers, monasteries, a university, and other enterprises, founded by his father, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In July 2018, Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche stepped back from his duties due to an investigation into sexual misconduct and power abuse.[1] He resumed teaching in Nepal in March 2020. Further teaching was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Biography

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was born Ösel Rangdröl Mukpo in Bodhgaya, India on November 15, 1962.[2]: 157 His father, Chögyam Trungpa, was a Buddhist monk who fled Tibet in 1959 (at age 20) and gradually became the head of a large party of refugees. His mother, Könchok Paldrön, was a young nun who met Trungpa in Tibet and fled with him to India.[3] For several years, Mukpo lived with his mother in a Tibetan refugee camp in northwest India.[3][4] His father left India in early 1963 to study at Oxford University.[4]: 72 At the age of seven, he went to live with his father at Samye Ling in Scotland.[3] Trungpa moved to the United States in 1970, and Ösel Mukpo joined his father there, in Boulder, Colorado along with his new stepmother Diana Mukpo in 1972.[2]: 157 [4]: 120 Ösel Mukpo has two younger half brothers (Gesar Mukpo and Tagtrug “Taggie” Mukpo) and one younger step brother (Ashoka Mukpo).[3]

In 1979, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche performed a ceremony officially investing his son Ösel Rangdröl with the title of Sawang ("earth lord"). This confirmed Ösel as his Shambhala heir and the future Sakyong.[2]: 204 After his father's death in 1987, the Sawang moved to Nepal and studied with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche for three years, while Osel Tendzin, the Vajra Regent, succeeded Trungpa Rinpoche as Buddhist lineage holder and head of the various organizations established by Trungpa, including Vajradhatu, Shambhala Training, and Naropa University.[2]: 406 When Tendzin died in 1990, the Ösel Mukpo was acknowledged as Trungpa's successor in the Kagyu, Nyingma and Shambhala lineages and head of the organizations.[2]: 410–411 In May 1995 he was formally enthroned as Sakyong at a ceremony performed by Penor Rinpoche. After the enthronement, Penor Rinpoche recognized Mukpo as the tulku of Mipham the Great,[2]: 413 after which he has been known by the title Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche.

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche is the head of the Shambhala organization, a global network of meditation and retreat centers. He has written several books, including the national bestseller Turning the Mind into an Ally, Ruling Your World, Running with the Mind of Meditation, and The Shambhala Principle. His most recent book, The Lost Art of Conversation, was released in October 2017. In 2018, he stepped back from all teaching and administrative duties due to an investigation and public discussion of his alleged sexual and organizational misconduct.[5] He resumed teaching in March 2020, instructing a group of 108 students in Nepal.[6] Further teaching at an event in France in June 2020 was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[7]

Investigation of sexual assault and power abuse

In February 2018, Buddhist Project Sunshine, an organization founded as a survivors' network for former Shambhala members,[8] reported multiple allegations of sexual assault within the Shambhala community.[9] In June 2018, Buddhist Project Sunshine issued a second report detailing sexual misconduct by Sakyong Mipham that occurred as recently as 2011 and claimed that those within Shambhala International had concealed the misdeeds.[10][5] In response, Sakyong Mipham stepped aside from his leadership role and the Shambhala governing council resigned.[1][11] Sakyong Mipham also issued a statement saying "...that some of these women have shared experiences of feeling harmed as a result of these relationships. I am now making a public apology."[12] In July 2018, Naropa Institute removed him from their board following the allegations of sexual misconduct.[13]

In August 2018, Buddhist Project Sunshine released another report containing further allegations against Sakyong Mipham that included sexual encounters with minors,[14][15] a charge that the Sakyong has denied.[16] In December 2018, the Larimer County, Colorado Sheriff's Office opened an investigation of the allegations of sexual assault.[17][18] The investigation was closed in February 2020, and no charges were filed.[19] In February 2019, Shambhala International's interim governing council issued a report by Wickwire Holm, a Canadian law firm, that detailed two credible allegations of sexual misconduct against Sakyong Mipham. [20][21][22] Later that month, six members of his Kusung (body protectors) wrote an open letter corroborating a pattern of physical and sexual misconduct and other concerns.[23][24] Sakyong Mipham subsequently stated that he would cease teaching for the "foreseeable future".[25] He returned to teaching in March, 2020, instructing a group of 108 students in Nepal.[6] In September 2020, The Walrus published an investigative report detailing a culture of abuse dating back to early days of the Shambhala Buddhist organization, with all three leaders of the organization, including its founder, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, having been credibly accused of sexual misconduct and abuse of power.[26]

Lineage of Sakyongs

The Sakyong holds and propagates the teachings of Shambhala. This tradition emphasizes confidence in the basic goodness of all beings and teaches courageous rulership based on wisdom and compassion. The term "Sakyong" literally means "earth-protector" in Tibetan, although it is colloquially understood to mean "king." Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche is regarded by his followers as a chögyal (Sanskrit dharmaraja) – "king of truth" – who combines the spiritual and worldly paths. In the Shambhala religion, the first Dharmaraja of Shambhala, Dawa Sangpo, was said to have been empowered directly by the Buddha. Shambhala Buddhists believe the Sakyong to be the earthly embodiment or emanation of the Rigden – mythical kings of Shambhala – and in this sense believe him to be a tulku (Tibetan), or nirmanakaya (Sanskrit) of the Rigden.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche is regarded as the first in this lineage of Sakyongs, and as such he is referred to as the "Druk Sakyong", or "Dragon Earth-Protector".

Sakyong Wangmo and family

The consort of the Sakyong is referred to as the Sakyong Wangmo. The first Sakyong Wangmo was Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche's wife, Diana Mukpo. The current Sakyong Wangmo is Sakyong Mipham's wife Khandro Tseyang Ripa Mukpo, the daughter of Terton Namkha Drimed Rabjam Rinpoche. The Sakyong and Sakyong Wangmo were married on 10 June 2006 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[27] Khandro Tseyang was officially empowered as Sakyong Wangmo by Penor Rinpoche at a ceremony in Halifax in August 2008.[28] The Sakyong and Sakyong Wangmo have three daughters. The first, Drukmo Yeshe Sarasvati Ziji Mukpo (Lady Dragon Wisdom), was born on 11 August 2010. The second, Jetsun Yudra Lhamo Yangchen Ziji Mukpo, was born in March 2013.[29] The third, Dzedrön Ökar Yangchen Ziji Mukpo, was born on 10 April 2015.[30]

Bibliography

Books

- The Lost Art of Good Conversation, Harmony Books, 2017, ISBN 9780451499431

- The Shambhala Principle: Discovering Humanity's Hidden Treasure, Harmony Books, 2013, ISBN 0770437435

- Running with the Mind of Meditation: Lessons for Training Body and Mind, Harmony Books, 2012, ISBN 0307888169

- Ruling Your World: Ancient Strategies for Modern Life, Morgan Road Books, 2005, ISBN 0-7679-2065-1

- Turning the Mind into an Ally, Riverhead Books, 2004, ISBN 1-57322-345-X

Articles

- It's All in the Mind in Shambhala Sun, November 2006.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Bundale, Brett (July 9, 2018). "Shambhala leader steps aside amid sexual misconduct allegations". CBC News.

- ^ a b c d e f Hayward, Jeremy (2008). Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-546-6.

- ^ a b c d Midal, Fabrice (2004). Chogyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 9780834821866.

- ^ a b c Mukpo, Diana J. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1-59030-256-7.

- ^ a b "The 'King' of Shambhala Buddhism Is Undone by Abuse Report". The New York Times. 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ a b "Rigden Nepal Pilgrimage March 8-15, 2020". Shambhala Report. 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Rigden Abhisheka – Repeaters POSTPONED". Shambhala Dechen Chöling.

- ^ "Buddhist Project Sunshine". andreamwinn.com. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M. "Project Sunshine: Final Report, February 27, 2017 –February 15, 2018" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M. (2018-06-28). "Buddhist Project Sunshine Phase 2 Final Report" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. et al. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ O'Connor, Kevin (2018-10-08). "Vermont Buddhists face their own MeToo moment". VTDigger. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Biddlecombe, Wendy Joan (28 June 2018). "Shambhala head Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche accused of sexual abuse in new report". Tricycle. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Boulder's Naropa University removes Shambhala International leader from its board". Boulder Daily Camera. 2018-07-06. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M.; Merchasin, Carol (2018-08-23). "Buddhist Project Sunshine Phase 3 Final Report; The nail: Bringing things to a clear point" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Agsar, Wendy Joan Biddlecombe (2018-08-23). "Report Reveals New Sexual Assault Allegations Against Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Bundale, Brett (2018-08-23). "Buddhist leader accused of sexual misconduct denies new allegations". CBC. CBC News. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Eaton, Joshua (2018-12-09). "Colorado police investigating alleged sexual assaults by Buddhist leaders". ThinkProgress. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Barnett, Jackson (2018-12-12). "Larimer County sheriff investigating "possible criminal activity" at Shambhala Mountain Center". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Julig, Carina (2020-02-18). "Larimer County Closes Investigation into Shambhala Mountain Center". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ Shambhala Interim Board (2019-02-03). "Report to the Community on the Wickwire Holm Claims Investigation into Allegations of Sexual Misconduct". Document cloud. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Barnett, Jackson (2019-02-03). "Shambhala report details sexual misconduct from Buddhist leader Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche". The Denver Post. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Bundale, Brett (2019-02-04). "Report finds 'sexual misconduct' by leader of Buddhist group". CBC. CBC News. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Long-Serving Kusung (2019-02-16). "An Open Letter to the Shambhala Community". drive.google.com. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ Bousquet, Tim (2019-02-19). "Six former members of the Shambhala inner circle write an open letter detailing physical, sexual, and psychological abuse at the hands of Mipham Mukpo". Halifax Examiner. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ "Shambhala Buddhist leader drops teaching in wake of report on sexual misconduct". Estevan Mercury. 2019-02-21. Archived from the original on 2019-02-25.

- ^ "Survivors of an International Buddhist Cult Share Their Stories | The Walrus". 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ Armstrong, Jane (3 June 2006). "Heaven and Halifax at Buddhist "royal wedding"". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Bodley, Laurie (Winter 2008–2009). "The Sakyong Wangmo empowerment" (PDF). The Dot. 6 (3): 1, 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Brooks Arenburg, Patricia (13 March 2013). "Halifax's Shambhala royal family welcomes second child". The Chronicle Herald. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Watters, Haydn (13 April 2015). "Shambhala Buddhist community's queen gives birth in Halifax". CBC News Nova Scotia. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

References

- Hayward, Jeremy (2008) Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa ISBN 0-86171-546-2