Tower of London test

The Tower of London test is a well-known test used in applied clinical neuropsychology for the assessment of executive functioning specifically to detect deficits in planning,[1][2] which may occur due to a variety of medical and neuropsychiatric conditions. It is related to the classic problem-solving puzzle known as the Tower of Hanoi.

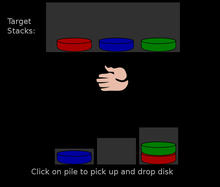

The test consists of two boards with pegs and several beads with different colors. The examiner (usually a clinical psychologist or a neuropsychologist) uses the beads and the boards to present the examinee with problem-solving tasks. Several variants of the test exist. Shallice's original test used three beads and pegs with different heights, although later researchers have generalized this to more beads without a peg height restriction.[3] Versions of the test are available from a number of sources, including a stand-alone test by William Culbertson and Eric Zillmer (published by Drexel University) and a child/adolescent version that is part of the original NEPSY neuropsychological battery of tests by Marit Korkman, Ursula Kirk, and Sally Kemp (although removed from the second edition). A computerised variant, known as the Stockings of Cambridge test, is available as part of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB).

One common use is for diagnosis of executive impairment. The performance of the examinee is compared to representative samples of individuals the same age in order to derive hypotheses about the person's executive cognitive ability, especially as it may relate to brain damage. A certain degree of controversy surrounds the test's construct validity.[4]

References

- ^ Shallice, T. (1982). "Specific impairments of planning". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 298 (1089): 199–209. doi:10.1098/rstb.1982.0082. PMID 6125971.

- ^ Phillips, LH; et al. (2001). "Mental planning and the Tower of London task". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology - Section A-Human Experimental Psychology. 54 (2): 579–597. doi:10.1080/02724980042000237. PMID 11394063.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Phillips, L. H. (1999). "The role of memory in the Tower of London task". Memory. 7 (2): 209–231. doi:10.1080/741944066. PMID 10645380.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ KAFER, K. L. (1997). "On Testing the Face Validity of Planning/Problem-Solving Tasks in a Normal Population". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 3 (2): 108–119. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links