Horace de Vere Cole

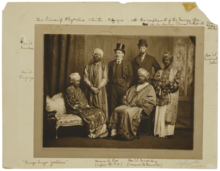

William Horace de Vere Cole (5 May 1881 – 25 February 1936) was an eccentric prankster born in Ballincollig, County Cork, Ireland. His most famous prank was the Dreadnought hoax where he and several others in blackface,[1] pretending to be an Abyssinian prince and his entourage, were given a tour of the Royal Navy ship HMS Dreadnought.

Family background and early life

[edit]Cole was the son of British Army officer William Utting Cole, a major in the 3rd Dragoon Guards who died of cholera in India when his son was a child.[2] His mother, Mary de Vere, was a niece and heiress of politician Sir Stephen de Vere, 4th Baronet.[3] Cole was a great-nephew of the Anglo-Irish poet Aubrey de Vere. Horace's paternal grandfather had made his fortune dealing in quinine. His mother's family claimed kinship with the de Vere Earls of Oxford, including 17th Earl Edward de Vere, who some believe wrote the plays and poems of William Shakespeare,[4] and the right to the position of Lord Great Chamberlain of England.[2] A bout of diphtheria at the age of ten seriously affected his hearing for the remainder of his life. A few years later, he was sent as a boarder to Eton College.[5]

During the Second Boer War, Cole was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Yorkshire Hussars, in which he quickly rose to the rank of acting captain. He was wounded by a dumdum bullet on 2 July 1900 and recuperated from shrapnel wounds at the Red Cross hospital in Kroonstad until September that year. He was subsequently invalided out of the army, donating the £1,800 he received from cashing in his disability pension to the war widows and orphans fund.[6]

On his return to England, Cole went up Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1902, although he did not complete his degree.[7]

When his paternal grandmother, Jane, died in 1906, Cole inherited, inter alia, West Woodhay House in the parish of West Woodhay in southern Berkshire. He was unable to afford the upkeep and in 1912 sold the property to his uncle, Alfred Clayton Cole, who later became Governor of the Bank of England.[8][9]

Pranks

[edit]

As an undergraduate at Cambridge, Cole posed as the uncle of the Sultan of Zanzibar—who was visiting London at the time—to make a ceremonial visit to his own college, accompanied by his friend Adrian Stephen (the brother of Virginia Woolf).[10] Cole's best-known trick was the Dreadnought hoax on 7 February 1910, when he fooled the captain of the Royal Navy warship HMS Dreadnought into taking him and a group of his friends in blackface,[1] including Virginia Woolf, for an official Abyssinian delegation. On occasion, Cole would wander the streets with a cow's teat poking through the open fly of his trousers; once he judged he had caused optimum outrage, he would cut off the offending protrusion with a pair of scissors.[11] On honeymoon with his first wife in Italy, on April Fools' Day 1919 Cole dropped horse manure onto Venice's Piazza San Marco—a city with no horses that could be reached only by boat.[12]

Spending most of his later life in London, Cole executed a series of bold jokes and escapades aimed to deflate pompous figures of authority. His targets included members of parliament, city business owners, and naval officers. On one occasion, he directed a group of like-minded friends dressed as workmen as they dug a trench across Piccadilly. On another, he challenged an old schoolfriend from Eton, the newly elected Conservative Member of Parliament Oliver Locker-Lampson, to race him on a London street to the nearest corner, giving him a 10-yard head start. Cole had already slipped his gold watch into his friend's pocket, and with Locker-Lampson running ahead at full speed, Cole waited till they were passing a policeman and began to yell, "Stop thief!" Locker-Lampson was promptly arrested and the watch was found. After savouring the moment, Cole explained that it was all a joke, and both men were told to go on their way. Unfortunately, Cole began dangerously waving his stick as though conducting an imaginary band, and both men were arrested and taken into custody. No charge was brought against Locker-Lampson, but Cole was found guilty of a breach of the peace and fined £5.[citation needed]

According to legend, Cole once hosted a party at which the guests discovered that they all had the word "bottom" in their surnames.[13] According to another story he bought tickets for particular seats at a theatrical performance he considered pretentious and distributed them to eight bald men whose heads, painted with a single letter, spelled out the word "B-O-L-L-O-C-K-S" (another source claims it was four men's heads making the word F-U-C-K),[14] which was legible from the circle and boxes above.[15][16]

With his mane of hair and bristling moustache, in the 1920s, Cole was sometimes mistaken for the Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald, causing dismay when Cole launched into a fierce public attack on Labour. His sister Annie married the future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who was asked by Annie what he thought of Cole and later commented, "I was obliged to say what I did think, but fortunately it appeared that was her opinion too and she was not at all inclined to be proud of her brother's exploit... I think he must be a little mad."[17]

Cole has also been suspected of the Piltdown Man hoax.[16]

Personal life

[edit]In 1918, Cole fell in love with the eighteen-year-old Irish heiress Denise Lynch. Owing to the fortune she stood to inherit, she was a ward of the Irish Chancery and prevented from marrying until the age of 21. Lynch was eventually released from the wardship and married Cole on 30 September 1918 in Dublin.[18] She subsequently gave birth to a daughter, Valerie.[19] The marriage ended in 1928, and he went into voluntary exile in France after losing all his money in Canadian land speculation.

In 1931, he married a former scullery maid and waitress at the Veeraswamy Indian restaurant, Mabel Winifred Mary Wright (later Mavis Wheeler, 1908–1970), who in 1935 gave birth to a son, Tristan de Vere Cole, who was the natural son of the artist Augustus John.

Cole died of a heart attack in Honfleur, France the following year and was buried at West Woodhay.

Mabel later married the archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, who afterwards divorced her on the grounds of her adultery with Lord Vivian.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b "The Dreadnought Hoax". Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ a b Downer 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b Grumley-Grennan, Tony (2010). Tales of English Eccentrics. Lulu.com. pp. 119–121. ISBN 978-0-9538922-4-2.

- ^ Holroyd, Michael (1996). Augustus John: The new biography. London: Chatto & Windus.

- ^ Downer 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Downer 2011, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Stansky, Peter (1997). On Or about December 1910: Early Bloomsbury and Its Intimate World. Harvard University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-674-63606-4.

- ^ "Parishes; West Woodhay". British History Online. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Downer 2011, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Martyn Downer, The Sultan of Zanzibar: The Bizarre World and Spectacular Hoaxes of Horace de Vere Cole (London: Black Spring Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-9482-3843-7), p. 44

- ^ "Horace de Vere Cole—The Great Prankster of Britain". The Historian's Hut. 30 August 2017.

- ^ Le Vay, Benedict (2011). Ben Le Vay's Eccentric Cambridge. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-84162-427-3.

- ^ Ash, Russell (2007). Morecock, Fartwell, & Hoare: A Collection of Unfortunate But True Names. London: Headline. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-312-54535-2.

- ^ Downer 2011, p. 184.

- ^ Le Vay, Benedict (2011). Ben Le Vay's Eccentric Cambridge. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84162-427-3.

- ^ a b Davis, Wes (1 April 2006). "A Fool There Was". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Dilks, David (2002). Neville Chamberlain. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-521-89401-2.

- ^ Downer 2011, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Downer 2011, p. 204.

- Sources

- Downer, Martyn (2011). The Sultan of Zanzibar: The Bizarre World and Spectacular Hoaxes of Horace De Vere Cole. London: Black Spring Press. ISBN 9780948238468.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard. "Cole, (William) Horace De Vere". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/61609. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)