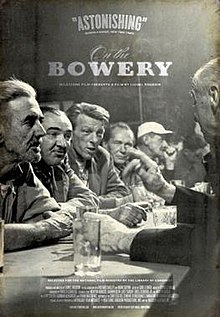

On the Bowery

| On the Bowery | |

|---|---|

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Lionel Rogosin |

| Written by | Mark Sufrin (uncredited) |

| Produced by | Lionel Rogosin |

| Starring | Ray Salyer Gorman Hendricks Frank Matthews |

| Cinematography | Richard Bagley (uncredited) |

| Edited by | Carl Lerner |

| Music by | Charles Mills |

| Distributed by | Film Representations Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 65 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

On the Bowery is a 1956 American docufiction film directed by Lionel Rogosin. The film, Rogosin's first feature[1] was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film.[2]

After the Second World War, Lionel Rogosin made a vow to fight fascism and racism wherever he found it. In 1954, he left the family business, the Beaunit Mills-American Rayon Corporation, in order to make films in accordance with his ideals. As he needed experience, he looked around for a subject and was struck by the plight of the men on the Bowery, and he determined that a portrayal of their daily lives on the streets and in the bars of the New York City neighborhood would make a strong film. Thus, On the Bowery served as Rogosin's practice film for the subsequent filming of his anti-apartheid film Come Back, Africa (1960).

In 2008, On the Bowery was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

Plot

[edit]The film chronicles life on New York's skid row, which then was the Bowery, focusing on three days in the life of a small group of its residents. Its principal characters are Ray Salyer, a railroad worker who has just arrived on the Bowery after railroad work, and two older men: Gorman Hendricks, a longtime Bowery resident, and Frank Matthews, who collects rags and cardboard on a pushcart and dreams of escaping to the South Seas.

Salyer wanders into a bar and is befriended by drunks he meets there. Among them is Hendricks, who steals his suitcase while Salyer is unconscious after heavy drinking.[4] Salyer, without money or possessions, seeks day labor on a truck, and seeks shelter at the Bowery Mission. But he does not spend the night and returns to drinking.

Toward the end of the film, Hendricks shares with Salyer a small amount of cash he had obtained. He tells Salyer that he received the money from a fellow who owed it to him. In reality, however, Hendricks got the cash by selling the items he found in Salyer's suitcase. Salyer is grateful and vows to use the money to buy a new shirt and pants, get "cleaned up", and escape life in the Bowery. The film concludes with Salyer's leaning on a Bowery lamppost.

Production

[edit]After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, Rogosin worked first as a chemical engineer and earned enough to finance his first feature. He was influenced by Robert Flaherty and Vittorio De Sica as well as the 1930 film adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front. His original plan was to make a film about apartheid in South Africa. With $30,000 in financing, he decided to focus on the Bowery as a practice project. He researched the area for six months before filming and interviewed physicians at Bellevue Hospital. The original intent was to create a film critical of capitalist society and "what brutal world created these broken lives?" Writer Mark Sufrin, who collaborated with Rogosin on the film, said the idea "was to extract a simple story from the Bowery itself."[1]

Rogosin got to know the street and the men intimately, befriending Ray Salyer as he was seeking day labor, and was delighted to find that his personal story was the one the filmmakers wanted to tell. He also met Gorman Hendricks, a longtime Bowery resident.[1]

While researching the film he met Sufrin and cinematographer Dick Bagley, who was recently part of the crew of Sydney Myers' The Quiet One. Bagley was himself an alcoholic, and died five years later. Rogosin also obtained the cooperation of the Bowery Mission, where one sequence was filmed. Shooting took place over a three-month period, beginning in July 1955. Bagley hid his 35 millimeter Arriflex camera under a bundle to shoot some bar scenes. Other filming was done from the back seat of a car.[1]

When filming began, the Third Ave El had ceased running but had not yet been torn down, so the dark shadows the El cast on the Bowery were still present, adding to the dingy atmosphere. The actors for the film were taken off the street, and spoke in their own slang, only guided what to say. Direction was aimed at "defining the action but not gesture or inflection," Sufrin later said in an article in Sight and Sound.[1]

The filmmakers encountered many difficulties when making the film. Cast members were arrested and returned to the street with shaves and haircuts, making it hard to match new material with what was filmed. Some simply disappeared. There was interference by police. Shooting at night without lights was difficult, and the El was in the process of being demolished as the film was being shot.[1]

Editing of the film took six months, about double the amount of time it should have taken, due to Rogosin's inexperience. He hired Carl Lerner to complete the editing. Charles Mills, who had won a Guggenheim Fellowship, wrote the score.[1]

Cast

[edit]- Ray Salyer (1916–1963) was born in Ashland, Kentucky and raised in North Carolina. He was a veteran of combat service in the U.S. Army during World War II.[5] Salyer was offered a $40,000 Hollywood contract after the film appeared, but declined and soon disappeared. He died in New York City, possibly the Bowery, from the effects of alcoholism in 1963.[6][7]

- Gorman Hendricks (d. 1956) had been a newspaper reporter in Washington D.C., and once had gone to jail rather than disclose his sources for an article on speakeasies.[8] He died in New York of cirrhosis of the liver just weeks before the film opened.[9] Rogosin helped both men and took care of Hendricks' burial.[7]

Reception and legacy

[edit]In September 1956, Rogosin became the first American director to win the Best Documentary award at the Venice Film Festival with On the Bowery, but it was shunned at the festival by Clare Boothe Luce, the American ambassador to Italy.[2]

Distribution was extremely difficult because of the downbeat subject matter and a dismissive review by influential New York Times critic Bosley Crowther. When it was opened in New York in March 1957, Crowther panned the film as "a dismal exposition." While praising the photography, editing and music, Crowther said the story was "a shade too fictional to be believed," and called the film "merely a good montage of good photographs of drunks and bums, scrutinized and listened to ad nauseam.[1][2]

The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and released in the U.S. in 1957.[10]

On the Bowery has come to be viewed as an incisive examination of alcoholism, and established Rogosin's reputation as an independent filmmaker. Among the independent filmmakers influenced by Rogosin and the film were John Cassavetes and Shirley Clarke, who employed many of his techniques in filming The Cool World (1963).[1]

Years later in a review of the 2015 film Mekko, Variety film critic Dennis Harvey mentioned On the Bowery, along with The Exiles (1961), as being two classic films set on skid row.[11]

Home media

[edit]Milestone Films released On the Bowery on DVD and Blu-ray in 2012.[12]

Awards

[edit]- Grand Prize in the Documentary and short film Category, Venice Film Festival, 1956

- British Film Academy Award, Best Documentary of 1956

- The Robert Flaherty Award, 1957

- Nominated for an Academy Award, 1957[10]

- Gold Medal Award, Sociological Convention, University of Pisa 1959

- Selected as one of the "Ten Best Movies of Ten Years Between 1950-1959" by Richard Griffith, Museum of Modern Art Film Library

- Festival of Popoli, 1971

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Daniel, Eagan (2010). America's film legacy: the authoritative guide to the landmark movies in the National Film Registry. National Film Preservation Board. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 523–24. ISBN 978-0826429773. OCLC 676697377 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Crowther, Bosley (March 19, 1957). "Screen: 'On the Bowery'; Documentary at 55th Street Playhouse Offers Sordid Lecture on Temperance". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn (January 29, 2012). "On the Bowery | The Films of Lionel Rogosin, Volume 1". DVD Talk. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ Balaban, Dan (March 27, 1957). "Bowery Film Star | Ray Salyer on the Way From Here to ...?". The Village Voice. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved June 9, 2022 – via Google News.

- ^ Family reference at Salyer-L Archives

- ^ a b Doros, Dennis (June 19, 2013). "Whatever happened to Ray Salyer? Now it can be told!". Milestone Films. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ "In Memoriam | Mary Elizabeth Pierce". Fairfax Bar Association. Fairfax County, Virginia. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

Her father was Gorman Hendricks, a muckraking Washington journalist who gained celebrity for going to jail rather than disclose his sources for a story about speakeasies, and later played himself in the 1956 film "On the Bowery".

- ^ Jones, J.R. (February 16, 2012). "One drink over the line". Chicago Reader. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ a b "The 30th Academy Awards (1958) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2011.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (September 11, 2015). "Toronto Film Review: 'Mekko'". Variety. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (February 24, 2012). "Out of the Bowery's Shadows (Then Back In)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- "Village-Made Bowery Film Wins Top Prize at Venice". The Village Voice. September 12, 1956.