Lemon shark: Difference between revisions

Oilybohunk7 (talk | contribs) |

GrahamBould (talk | contribs) m Improve wording |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Lemon sharks are a popular choice for study by scientists as they survive well in captivity, unlike many other species such as the [[great white shark]], which dies in captivity because of food refusal. The species is the best known of all sharks in terms of behaviour and [[ecology]], mainly thanks to the enormous effort of Dr. Samuel Gruber at the [[University of Miami]] who has been studying the lemon shark both in the field and in the laboratory since 1967. The population around the [[Bimini Islands]] in the western [[Bahamas]], where Dr Gruber's field station, Bimini Biological Field Station, is situated, is probably the best known of all shark populations. As of 2007, it is experiencing a severe population decline and may disappear altogether due to destruction of the mangroves for construction of a golf [[resort]]. There have been 22 lemon shark attacks since 1580 with no deaths. |

Lemon sharks are a popular choice for study by scientists as they survive well in captivity, unlike many other species such as the [[great white shark]], which dies in captivity because of food refusal. The species is the best known of all sharks in terms of behaviour and [[ecology]], mainly thanks to the enormous effort of Dr. Samuel Gruber at the [[University of Miami]] who has been studying the lemon shark both in the field and in the laboratory since 1967. The population around the [[Bimini Islands]] in the western [[Bahamas]], where Dr Gruber's field station, Bimini Biological Field Station, is situated, is probably the best known of all shark populations. As of 2007, it is experiencing a severe population decline and may disappear altogether due to destruction of the mangroves for construction of a golf [[resort]]. There have been 22 lemon shark attacks since 1580 with no deaths. |

||

==The |

==The magnetic field== |

||

All sharks have electroreceptors concentrated in their heads called the [[Ampullae of Lorenzini]]. These receptors detect electrical pulses emitted by potential prey. Lemon sharks however have very poor eyesight. The cannot see well to find their food, and they are bottom dwellers, |

All sharks have electroreceptors concentrated in their heads called the [[Ampullae of Lorenzini]]. These receptors detect electrical pulses emitted by potential prey. Lemon sharks however have very poor eyesight. The cannot see well to find their food, and they are bottom dwellers, but make up for this by having extremely good magnetic sensors in the nose. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 04:01, 30 July 2008

| Lemon shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. brevirostris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Negaprion brevirostris | |

| |

| Range (in blue) | |

The lemon shark, Negaprion brevirostris, is a shark belonging to the family Carcharhinidae that can grow 10 feet long (3 meters)[1].

Distribution and habitat

The lemon shark is found mainly along the subtropical and tropical parts of the Atlantic coast of North and South America. This species can be found as well in Pacific islands of Polynesia - French Polynesia - Tahiti, the Cook Islands, and Tonga. The longest lemon shark recorded was 12 ft long, but they are usually 8 to 10 ft. They like tropical water, and like to stay at moderate depths.

Reproduction

Lemon sharks are viviparous, females giving birth to between 4 and 17 young every other year in warm and shallow lagoons. The young have to fend for themselves and remain in shallow water near mangroves until they grow larger. With increasing size, the sharks venture further away from their birth place. At maturity at a size of 1.5 to 2 m and an age of 12 to 15 years, they leave shallow water and move into deeper waters offshore. However, little is known of this life stage. Maximum recorded length and weight is 340 cm and 183 kg. They can be extremely aggressive and protective if young sharks are around.[1]

Recent work in genetics by Drs Kevin Feldheim, Sonny Gruber and Mary Ashley may suggest that adult sharks move over hundreds of km to mate, or populations far apart may have been separated in recent time. Further research in this area would be of immense importance for the understanding of the lemon shark's breeding behaviour and ecology.

Importance to humans

Lemon sharks are a popular choice for study by scientists as they survive well in captivity, unlike many other species such as the great white shark, which dies in captivity because of food refusal. The species is the best known of all sharks in terms of behaviour and ecology, mainly thanks to the enormous effort of Dr. Samuel Gruber at the University of Miami who has been studying the lemon shark both in the field and in the laboratory since 1967. The population around the Bimini Islands in the western Bahamas, where Dr Gruber's field station, Bimini Biological Field Station, is situated, is probably the best known of all shark populations. As of 2007, it is experiencing a severe population decline and may disappear altogether due to destruction of the mangroves for construction of a golf resort. There have been 22 lemon shark attacks since 1580 with no deaths.

The magnetic field

All sharks have electroreceptors concentrated in their heads called the Ampullae of Lorenzini. These receptors detect electrical pulses emitted by potential prey. Lemon sharks however have very poor eyesight. The cannot see well to find their food, and they are bottom dwellers, but make up for this by having extremely good magnetic sensors in the nose.

See also

References

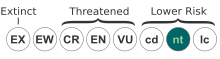

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is near threatened

- "Negaprion brevirostris". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 23 January.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Negaprion brevirostris". FishBase. March 2005 version.

- Washington Post, 2005, Aug. 22nd: "Scientists Fear Oceans on the Cusp Of a Wave of Marine Extinctions"