Jami: Difference between revisions

→His works: disambig about minority viewpoints |

rv - you cannot just tag articles because you personally don't like the content. You're supposed to provide alternative viewpoints. |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

==His works== |

==His works== |

||

{{NPOV-section}} |

|||

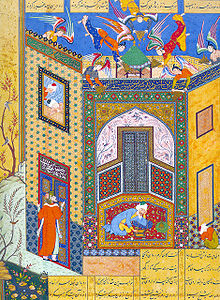

[[Image:Youth and suitors.jpg|thumb|left|'''Same youth conversing with suitors'''<br>Another illustration from the Haft Awrang]] |

[[Image:Youth and suitors.jpg|thumb|left|'''Same youth conversing with suitors'''<br>Another illustration from the Haft Awrang]] |

||

Jami wrote approximately eighty-seven books and letters, some of which have been translated into English. His works range from prose to poetry, and from the mundane to the religious. He has also written works of history. His poetry has been inspired by the ghazals of [[Hafez]], and his ''Haft Awrang'' is, by his own admission, influenced by the works of [[Nizami]]. |

Jami wrote approximately eighty-seven books and letters, some of which have been translated into English. His works range from prose to poetry, and from the mundane to the religious. He has also written works of history. His poetry has been inspired by the ghazals of [[Hafez]], and his ''Haft Awrang'' is, by his own admission, influenced by the works of [[Nizami]]. |

||

===Minority views=== |

|||

Acccording to Janet Afary, "Classical Persian literature — like the poems of Attar (died 1220), Rumi (d. 1273), Sa’di (d. 1291), Hafez (d. 1389), Jami (d. 1492), and even those of the 20th century Iraj Mirza (d. 1926) — are replete with homoerotic allusions, as well as explicit references to beautiful young boys and to the practice of pederasty."<ref>Janet Afary, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islam</ref> |

Acccording to Janet Afary, "Classical Persian literature — like the poems of Attar (died 1220), Rumi (d. 1273), Sa’di (d. 1291), Hafez (d. 1389), Jami (d. 1492), and even those of the 20th century Iraj Mirza (d. 1926) — are replete with homoerotic allusions, as well as explicit references to beautiful young boys and to the practice of pederasty."<ref>Janet Afary, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islam</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:23, 10 April 2006

From the Haft Awrang of Jami, in the story "A Father Advises his Son About Love." See Nazar ill'al-murd Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami (August 18, 1414–November 19, 1492) was the greatest Persian poet in the 15th century and the last great Sufi poet of Persia. His fame rests even more on his mystical authority than on his talents as a poet and writer.

Biography

He was born in a village near Jam, but a few years after his birth, his family migrated to the cultural city of Herat in present-day Afghanistan where he was able to study Peripateticism, mathematics, Arabic literature, natural sciences, and Islamic thought at the Nizamiyyah University of Herat.

Afterwards he went to Samarqand, the most important centre of scientific studies in the Islamic World and completed his studies there. He was a famous Sufi, and a follower of the Naqshbandiyyah sufi Order. At the end of his life he was living in Herat.

His teachings

In his role as Sufi shaykh, Jami expounded a number of teaching regarding following the Sufi path. In his view, love was the fundamental stepping stone for starting on the spiritual journey. To a student who claimed never to have loved, he said, "Go and love first, then come to me and I will show you the way."[1]

However, the use of "forbidden" themes such as the love of boys or the love of wine in Sufi teachings such as Jami's has been the topic of lively debate, with some claiming that the references are purely symbolic and mystical,[1] and others holding that they are the expression of authentic feelings and desires, whether or not they were actually acted upon.

His works

Another illustration from the Haft Awrang

Jami wrote approximately eighty-seven books and letters, some of which have been translated into English. His works range from prose to poetry, and from the mundane to the religious. He has also written works of history. His poetry has been inspired by the ghazals of Hafez, and his Haft Awrang is, by his own admission, influenced by the works of Nizami.

Acccording to Janet Afary, "Classical Persian literature — like the poems of Attar (died 1220), Rumi (d. 1273), Sa’di (d. 1291), Hafez (d. 1389), Jami (d. 1492), and even those of the 20th century Iraj Mirza (d. 1926) — are replete with homoerotic allusions, as well as explicit references to beautiful young boys and to the practice of pederasty."[2]

In his Nafahat al-Uns (Breaths of Fellowship), a biography of Sufi saints, he defends some of the greatest Persian mystics against accusations that their practice of shahid-bazi (the "witness-game", the contemplation of beautiful boys) is heretical. Among these are Al-Ghazali, Awhad al-Din Kirmani, and Farhruddin Iraqi. His argument was that the masters were absorbed in absolute beauty, and not trapped by the base form. In the cosmogony evolved by Jami, God himself is but a beautiful youth absorbed in the contemplation of his many qualities.[3]

Jami's view – a variation from the norm, – was that one should not discriminate against youths who were more mature: "Is it not the same youth as last year? ... It is true that he has increased in stature and his body is more vigorous. What impudence, what shame, what irreverence to cease to visit him and to desire his company." Jami himself was a practitioner of shahid-bazi, though he seems to have evaded being suspected of heresy. [4]

This aspect of his life and practice is reflected in many of his works. In his Baharistan (Spring Garden), Jami recounts the events in a Sufi monastery where all the dervishes are smitten with love for a beautiful boy. The khaneghah, the abbott, advises the boy not to be free with his favors:

- "Do not yield up the bridle you wear in the hands of the unworthy,

- "Do not admit the vulgar throng into your private dwelling,

- "Your face is a mirror most carefully polished,

- "Take care you do not rust this limpid mirror."

Finally, the abbott relents, admiting that "no one can lay down the law" to the youth and that he can freely associate – or not – with whomever he chooses. [5]

In his Haft Awrang (see manuscript), an anthology of seven alegorical poems on wisdom and love, he gives further evidence that the pederastic relationshp needs to be a spiritual one. In the section titled A Father Advises his Son About Love, a father instructs his son, when choosing a worthy male lover, to chose that man who sees beyond the mere physical and expresses a love for his inner qualities.

Divan of Jami

Among his works are:

- Baharistan (Abode of Spring) Modeled upon the Gulistan of Saadi

- Nafahat al-Uns (Breaths of Fellowship) Biographies of the Sufi saints

- Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones) His major poetical work

- Lawa'ih A treatise on Sufism

- Diwanha-i Sehganeh (Triplet Divans)

See also

- Ghazal

- List of Persian poets and authors

- Nazar ill'al-murd

- Pederasty in the Islamic lands

- Persian literature

Notes

- ^ William Chittick, "Jami on Divine Love and the image of wine", in Studies in Mystical Literature, 1/3 (1981), pp. 193-209

- ^ Janet Afary, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islam

- ^ "The Will Not to Know" in Murray and Roscoe, Islamic Homosexualities, NY, 1997; p.125

- ^ ibid., p.23

- ^ ibid., p.136

References

- E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing). 1998. ISBN 0-700-70406-X

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. ASIN B-000-6BXVT-K