UNIVAC 1103: Difference between revisions

m ISBNs (Build J/) |

|||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

* |

* Oral history interviews on ERA 1103, [[Charles Babbage Institute]], University of Minnesota. Interviewees include [http://purl.umn.edu/107209 William W. Butler]; [http://purl.umn.edu/107220 Arnold A. Cohen]; [http://purl.umn.edu/107551 William C. Norris]; [http://purl.umn.edu/107538 Frank C. Mullaney]; [http://purl.umn.edu/107538 Marvin L. Stein]; and [http://purl.umn.edu/107673 James E. Thornton]. |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Univac 1103}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Univac 1103}} |

||

Revision as of 19:54, 2 April 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

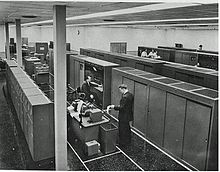

The UNIVAC 1103 or ERA 1103, a successor to the UNIVAC 1101, was a computer system designed by Engineering Research Associates and built by the Remington Rand corporation in October, 1953. It was the first computer for which Seymour Cray was credited with design work.[1]

History

Even before the completion of the Atlas (UNIVAC 1101), the Navy asked Engineering Research Associates to design a more powerful machine. This project became Task 29, and the computer was designated Atlas II.

In 1952, Engineering Research Associates asked the Armed Forces Security Agency (the predecessor of the NSA) for approval to sell the Atlas II commercially. Permission was given, on the condition that several specialized instructions would be removed. The commercial version then became the UNIVAC 1103. Because of security classification, Remington Rand management was unaware of this machine before this.

Remington Rand announced the UNIVAC 1103 in February 1953. The machine competed with the IBM 701 in the scientific computation market. In early 1954, a committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff requested that the two machines be compared for the purpose of using them for a Joint Numerical Weather Prediction project. Based on the trials, the two machines had comparable computational speed, with a slight advantage for IBM's machine, but the later was favored unanimously for its significantly faster input-output equipment.[2]

The successor machine was the UNIVAC 1103A or Univac Scientific, which improved upon the design by replacing the unreliable Williams tube memory with magnetic core memory, adding hardware floating point instructions, and a hardware interrupt feature.

Technical details

The system used electrostatic storage, consisting of 36 Williams tubes with a capacity of 1024 bits each, giving a total random access memory of 1024 words of 36 bits each. Each of the 36 Williams tubes was five inches in diameter. A magnetic drum memory provided 16,384 words. Both the electrostatic and drum memories were directly addressable: addresses 0 through 01777 (Octal) were in electrostatic memory and 040000 through 077777 (Octal) were on the drum.

Fixed-point numbers had a 1-bit sign and a 35-bit value, with negative values represented in ones' complement format.

Instructions had a 6-bit operation code and two 15-bit operand addresses.

Programming systems for the machine included the RECO regional coding assembler by Remington-Rand, the RAWOOP one-pass assembler and SNAP floating point interpretive system authored by the Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation of Los Angeles, the FLIP floating point interpretive system by Consolidated Vultee Aircraft of San Diego, and the CHIP floating point interpretive system by Wright Field in Ohio.

1103A

The UNIVAC 1103A or Univac Scientific was an upgraded version introduced in March 1956. Significant new features on the 1103A were its magnetic core memory, and the addition of interrupts to the processor. [3] The UNIVAC 1103A had up to 12,288 words of 36 bit magnetic core memory, in one to three banks of 4,096 words each.

Fixed-point numbers had a 1 bit sign and a 35 bit value, with negative values represented in ones' complement format. Floating-point numbers had a 1 bit sign, an 8 bit characteristic, and a 27 bit mantissa. Instructions had a 6 bit operation code and two 15-bit operand addresses.

The 1103A was contemporary and competitor to the IBM 704, which also employed vacuum tube logic, magnetic core memory, and hardware floating point.

See also

References

- ^ "Tribute to Seymour Cray". IEEE Computer Society. Archived from the original on 2010-05-01.

- ^ Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer, IBM's 360 and early 370 systems, MIT Press, 1991, ISBN 0-262-16123-0 pp. 23-34

- ^ Rául Rojas, Ulf Hashagen The first computers: history and architectures MIT Press, 2002 ISBN 0-262-68137-4, page 198

Further reading

- Oral history interviews on ERA 1103, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Interviewees include William W. Butler; Arnold A. Cohen; William C. Norris; Frank C. Mullaney; Marvin L. Stein; and James E. Thornton.