Chained library: Difference between revisions

m →External links: Remove stub template(s). Page is start class or higher. Also check for and do General Fixes + Checkwiki fixes using AWB |

Meredithka (talk | contribs) m Added more information on chained libraries and the recent interest in reconstructing and transforming them into museums. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Chained Library, Chelsea Old Church - geograph.org.uk - 493693.jpg|thumb|Chained Library, Chelsea Old Church. Unique in London churches, a mediaeval library, containing a "vinegar bible" of 1717. These were a gift of Sir [[Hans Sloane]].]]A '''chained library''' is a [[library]] where the books are attached to their [[bookcase]] by a chain, which is sufficiently long to allow the books to be taken from their shelves and read, but not removed from the library itself. |

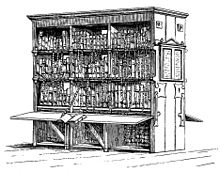

[[File:Chained Library, Chelsea Old Church - geograph.org.uk - 493693.jpg|thumb|Chained Library, Chelsea Old Church. Unique in London churches, a mediaeval library, containing a "vinegar bible" of 1717. These were a gift of Sir [[Hans Sloane]].]]A '''chained library''' is a [[library]] where the books are attached to their [[bookcase]] by a chain, which is sufficiently long to allow the books to be taken from their shelves and read, but not removed from the library itself. This would prevent theft of the library's materials.<ref>Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/</ref> The practice was usual for [[reference library|reference libraries]] (that is, the vast majority of libraries) from the [[Middle Ages]] to approximately the 18th century. However, since the chaining process was also expensive, it was not used on all books<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.</ref>. Only the more valuable books in a collection were chained<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.</ref>. This included reference books and large books<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.</ref>. |

||

It is standard for chained libraries to have the chain fitted to the corner or cover of a book. This is because if the chain were to be placed on the spine the book would suffer greater wear from the stress of moving it on and off the shelf. Because of the location of the chain attached to the book (via a ringlet) the books are housed with their spine facing ''away'' from the reader with only the pages' fore-edges visible (that is, the 'wrong' way round to people accustomed to contemporary libraries). This is so that each book can be removed and opened without needing to be turned around, hence avoiding tangling its chain. |

It is standard for chained libraries to have the chain fitted to the corner or cover of a book. This is because if the chain were to be placed on the spine the book would suffer greater wear from the stress of moving it on and off the shelf. Because of the location of the chain attached to the book (via a ringlet) the books are housed with their spine facing ''away'' from the reader with only the pages' fore-edges visible (that is, the 'wrong' way round to people accustomed to contemporary libraries). This is so that each book can be removed and opened without needing to be turned around, hence avoiding tangling its chain. To remove the book from the chain, the librarian would use a key.<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> |

||

[[File:Libraries in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods Figure 4.jpg|thumb|Chained library in Hereford Cathedral]] |

[[File:Libraries in the Medieval and Renaissance Periods Figure 4.jpg|thumb|Chained library in Hereford Cathedral]] |

||

The earliest example in England of a library to be endowed for use outside an institution such as a school or college was the [[Francis Trigge Chained Library]] in [[Grantham]], [[Lincolnshire]], established in 1598. The library still exists and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of later [[public library]] systems. [[Marsh's Library]] in Dublin, built 1701, is another non institutional library which is still housed in its original building. Here it was not the books that were chained, but rather the readers were locked into cages to prevent rare volumes from 'wandering'. There is also an example of a chained library in the [[Royal Grammar School, Guildford]] as well as at [[Hereford Cathedral]]. |

The earliest example in England of a library to be endowed for use outside an institution such as a school or college was the [[Francis Trigge Chained Library]] in [[Grantham]], [[Lincolnshire]], established in 1598. The library still exists and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of later [[public library]] systems. [[Marsh's Library]] in Dublin, built 1701, is another non institutional library which is still housed in its original building. Here it was not the books that were chained, but rather the readers were locked into cages to prevent rare volumes from 'wandering'. There is also an example of a chained library in the [[Royal Grammar School, Guildford]] as well as at [[Hereford Cathedral]]. While chaining books was a popular practice throughout Europe, it was not used in all libraries.<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.</ref> For example, in the library of [[Cambridge, England]], books were never chained.<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, 375-6.</ref> Some scholars have argued that this was the result of low literacy rates or a belief in the honesty of the town's residents.<ref>Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, 376</ref> This practice became less popular as printing increased and books became less expensive.<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> |

||

==Recent Interest in Saving and Preserving Chained Libraries== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Recently, there has been increased interest in reconstructing chained libraries. While only five chained libraries left that have survived intact throughout the world survived.<ref>Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/</ref> This includes the library built in the Church of St. Walburga, located in the small town of Zutphen in the Netherlands.<ref>Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/</ref> This library was build in 1564.<ref>Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/</ref> The library is now part of a museum that allows visitors to tour and view the library's original books, furniture, and chains.<ref>Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/</ref> |

|||

A lot of work has gone into rebuilding and preserving these great libraries.<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> For example, many workers, over a decade, and massive monetary donations were spent to restore the Mappa Mundi and Chained Library museum located in [[Hereford, England]].<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> Built over 900 years ago, the library fell into disrepair and faced destruction.<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> Like the chained library museum in Church of St. Walburga, this historical site is now open to the public.<ref>Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*In [[Terry Pratchett]]'s [[Discworld]] series of comic fantasy novels, the library of the magical Unseen University also has a number of chained books—however, in this case the purpose of the chains is to prevent the more vicious magical books from escaping or attacking passers-by. |

*In [[Terry Pratchett]]'s [[Discworld]] series of comic fantasy novels, the library of the magical Unseen University also has a number of chained books—however, in this case the purpose of the chains is to prevent the more vicious magical books from escaping or attacking passers-by. |

||

*[[David Williams (crime writer)|David Williams]] has written a mystery, ''Murder in Advent'', that features a chained library.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/david-williams-548864.html|title=David Williams obituary|last=Heald|first=Tim|work=The Independent|accessdate=10 November 2010}}</ref> |

*[[David Williams (crime writer)|David Williams]] has written a mystery, ''Murder in Advent'', that features a chained library.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/david-williams-548864.html|title=David Williams obituary|last=Heald|first=Tim|work=The Independent|accessdate=10 November 2010}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:02, 14 March 2014

A chained library is a library where the books are attached to their bookcase by a chain, which is sufficiently long to allow the books to be taken from their shelves and read, but not removed from the library itself. This would prevent theft of the library's materials.[1] The practice was usual for reference libraries (that is, the vast majority of libraries) from the Middle Ages to approximately the 18th century. However, since the chaining process was also expensive, it was not used on all books[2]. Only the more valuable books in a collection were chained[3]. This included reference books and large books[4].

It is standard for chained libraries to have the chain fitted to the corner or cover of a book. This is because if the chain were to be placed on the spine the book would suffer greater wear from the stress of moving it on and off the shelf. Because of the location of the chain attached to the book (via a ringlet) the books are housed with their spine facing away from the reader with only the pages' fore-edges visible (that is, the 'wrong' way round to people accustomed to contemporary libraries). This is so that each book can be removed and opened without needing to be turned around, hence avoiding tangling its chain. To remove the book from the chain, the librarian would use a key.[5]

The earliest example in England of a library to be endowed for use outside an institution such as a school or college was the Francis Trigge Chained Library in Grantham, Lincolnshire, established in 1598. The library still exists and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of later public library systems. Marsh's Library in Dublin, built 1701, is another non institutional library which is still housed in its original building. Here it was not the books that were chained, but rather the readers were locked into cages to prevent rare volumes from 'wandering'. There is also an example of a chained library in the Royal Grammar School, Guildford as well as at Hereford Cathedral. While chaining books was a popular practice throughout Europe, it was not used in all libraries.[6] For example, in the library of Cambridge, England, books were never chained.[7] Some scholars have argued that this was the result of low literacy rates or a belief in the honesty of the town's residents.[8] This practice became less popular as printing increased and books became less expensive.[9]

Recent Interest in Saving and Preserving Chained Libraries

Recently, there has been increased interest in reconstructing chained libraries. While only five chained libraries left that have survived intact throughout the world survived.[10] This includes the library built in the Church of St. Walburga, located in the small town of Zutphen in the Netherlands.[11] This library was build in 1564.[12] The library is now part of a museum that allows visitors to tour and view the library's original books, furniture, and chains.[13] A lot of work has gone into rebuilding and preserving these great libraries.[14] For example, many workers, over a decade, and massive monetary donations were spent to restore the Mappa Mundi and Chained Library museum located in Hereford, England.[15] Built over 900 years ago, the library fell into disrepair and faced destruction.[16] Like the chained library museum in Church of St. Walburga, this historical site is now open to the public.[17]

Chained Libraries in Popular Culture

- In Terry Pratchett's Discworld series of comic fantasy novels, the library of the magical Unseen University also has a number of chained books—however, in this case the purpose of the chains is to prevent the more vicious magical books from escaping or attacking passers-by.

- David Williams has written a mystery, Murder in Advent, that features a chained library.[18]

- In the film Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, the Restricted section of the library features chained books.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, p. 375-6.

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, 375-6.

- ^ Byrne, D. “Chained libraries.” History Today, 1987, 376

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/

- ^ Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/

- ^ Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/

- ^ Weston, J. (2013, May 10). "The Last of the Great Chained Libraries". Retrieved from http://medievalfragments.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/the-last-of-the-great-chained-libraries/

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Lopez, B. “New Chained Library of Hereford Cathedral Takes Royal Prize”. American Libraries, 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Heald, Tim. "David Williams obituary". The Independent. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

Bibliography

- Streeter, B. H. The Chained Library: a survey of four centuries in the evolution of the English library. London: Macmillan, 1931.

External links

- Alston, Robin. Library history database: chained libraries (covering England)

- The Mappa Mundi and Chained Library at Hereford Cathedral — accessed 26 June 2011

- Chetham's Medieval Library - Manchester, England[dead link]

- Wimborne Minster Chained Library — accessed 6 January 2007

- Oriel College Library — accessed 12 March 2007[dead link]

- A chained library surviving at a school (The Royal Grammar School, Guildford) — accessed 6 January 2007

- Another school's chained library (Bolton School Boys Division) — accessed 6 January 2007[dead link]

- Chain Reaction: The Practice of Chaining Books in European Libraries - An overview of the practice of chaining libraries — accessed 6 January 2007

- Marsh's Library - accessed 15 December 2007