Eloisa to Abelard: Difference between revisions

new second section begun |

completed second section |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

::He best can paint them who can feel them most. |

::He best can paint them who can feel them most. |

||

Whether this was deliberate or not, some fourteen imitations of his poem had been written by the end of the century, all but one of them cast as Abelard's reply to Eloisa and written in heroic couplets. Although Pope's poem provided the main inspiration, and was frequently mentioned by the authors in their prefaces, there was always Hughes' volume with its historical account in the background. In later volumes the dependency between the two was further underlined by the inclusion first of Pope's poem in the Hughes volume (in the 1769 edition) and then some of the principal responses in following editions. |

Whether this was deliberate or not, some fourteen imitations of his poem had been written by the end of the century, all but one of them cast as Abelard's reply to Eloisa and written in heroic couplets. Although Pope's poem provided the main inspiration, and was frequently mentioned by the authors in their prefaces, there was always Hughes' volume with its historical account in the background. In later volumes the dependency between the two was further underlined by the inclusion first of Pope's poem in the Hughes volume (in the 1769 edition) and then some of the principal responses in following editions. |

||

The poems in question are as follows: |

|||

[[File:Angelica Kauffmann 001.png|thumb|235px|left|The Parting of Abelard and Heloise by [[Angelica Kauffman]], before 1780, Hermitage Museum]] |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1720) by [[Judith Madan]].<ref>Hughes, p.172ff</ref> |

|||

*[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4qFYAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false ''Abelard to Eloisa''] (1725) by ''Petrus Abelardus'' [Richard Barford], “wherein we may observe how high we may raise the sentiments of our heart, when possessed of a great deal of wit and learning, with a most violent love”. |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1726) by [[Richard Savage]], prefaced by Pope's ''Eloisa to Abelard''.<ref>[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=zUsJAAAAQAAJ&dq=inauthor%3A%22Richard+Savage%22&q=Abelard#v=snippet&q=Abelard&f=false pp.119-150]</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1727) by William Pattison.<ref>In ''The Works of the British Poets'' vol.14, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=XnWw2AwVx-cC&pg=PA419&lpg=PA419&dq=%22Abelard+to+Eloisa%22&source=bl&ots=VWEgPohOY1&sig=4TxZVC-CUHDoDwCqYrZAdfB7eZg&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KepPVc_FMoPbUcH5gNAE&ved=0CDcQ6AEwBzge#v=onepage&q=%22Abelard%20to%20Eloisa%22&f=false pp.419-424]</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa, in answer to Mr Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard'' (1730) by James Delacour(t).<ref>[http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/d/Delacour_J/life.htm Publishing information]</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1747) by James Cawthorne (1719-1761).<ref>Hughes, p.178ff</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa by an unknown hand''.<ref>Hughes, p.189ff</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1777) by St. John Drelincourt Seymour.<ref>Hughes p.205ff</ref> |

|||

*''Abelard to Eloisa'' (1778) by Samuel Birch (1757-1841).<ref>Hughes, p.193ff</ref> |

|||

*[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Mq1YAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false ''Eloisa en deshabille, being a new version of Mr Pope’s celebrated epistle''] (1780, with two later editions). In this a burlesque version in [[anapaest]]ic measure appears opposite Pope's original. It has been ascribed to several authors, including [[Richard Porson]], but is now thought to be by [[John Matthews (physician)|John Matthews]]. |

|||

*[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IcNgAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false ''Eloisa to Abelard'']: ''an epistle, with a new account of their lives and references to their original correspondence'' (1785) by Thomas Warwick. This was an enlarged and corrected version of a work first published in 1882. |

|||

*[http://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/ecco/004794779.0001.000?rgn=main;view=fulltext ''Abelard to Eloisa''] by Edward Jerningham (1792). Also a Catholic, Jerningham gives a greater sense of the historical setting, especially the quarrel with [[Bernard of Clairvaux]] and Abelard's sentence of excommunication. |

|||

*''A Struggle between Religion and Love, in an epistle from Abelard to Eloisa'' by Sarah Farrell (1792).<ref>In ''Charlotte and other poems, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vBg_AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false pp.29-38]</ref> |

|||

* ''Abelard to Eloisa'', in an early collection of poems by [[Walter Savage Landor]] (1795). In his preface, Landor discusses the difficulty of following Pope, but a commentator has suggested that he was also familiar with Hughes letters.<ref>William Bradley, ''The early poems of Walter Savage Landor'', [https://archive.org/stream/earlypoemsofwalt00braduoft#page/20/mode/2up/search/Abelard pp.20-23]</ref> |

|||

Three of the poems above were written by young men of about 20: Pattison, Delacourt and Landor. Two women are included among the authors, of whom the earliest, Judith (Cowper) Madan, was a young disciple of Pope and published her poem before she was 20. Writing there from a male point of view, she matched Pope, who adopted a female identity in his poem.<ref>''The Routledge Anthology of Cross-Gendered Verse'', (2005)[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6KuIAgAAQBAJ&lpg=PA154&ots=jOZDMQri4h&dq=Judith%20Madan%20%20%22Abelard%20to%20Eloisa%22&pg=PA154#v=onepage&q=Judith%20Madan%20%20%22Abelard%20to%20Eloisa%22&f=false p.154]</ref> Two later women also took up the subject. [[Christina Rossetti]]'s "The Convent Threshold" (written in 1858) is, according to one source, “a thinly disguised retelling of Alexander Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard”,<ref>John Powell (ed), ''Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century'', Greenwood Publishing 2001, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3N3uj_wo-_kC&lpg=PA348&ots=MovGkPuEv1&dq=christina%20rossetti%20the%20convent%20threshold%20%22Eloisa%22&pg=PA348#v=onepage&q=christina%20rossetti%20the%20convent%20threshold%20%22Eloisa%22&f=false p.348]</ref> although others are more cautious in seeing an influence. The poem is a surging monologue of enlaced rhymes in [[octosyllable]]s, driving along its theme of leaving earthly passion behind and transmuting it to heavenly love.<ref>[http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/crossetti/bl-crossetti-convent.htm Etext]</ref> The Australian writer [[Gwen Harwood]] went on to use the situation as a weapon in the gender war. Writing under the assumed name of Walter Lehmann in 1961, she placed two modernistic sonnets, "Eloisa to Abelard" and "Abelard to Eloisa", in a magazine without its editors realising that the letters of their first lines spelt an offensive message.<ref>Peter L. Shillingsburg, ''Resisting Texts: Authority and Submission in Constructions of Meaning'', University of Michigan 1997, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=rk3o2VjqezoC&lpg=PA160&ots=xF-eHRzoSA&dq=Gwen%20Harwood%2C%20%22Eloisa%20to%20Abelard%22&pg=PA160#v=onepage&q=Gwen%20Harwood,%20%22Eloisa%20to%20Abelard%22&f=false p.160, sonnets on p.161]</ref> |

|||

Three more poems by males were written in the first half of the 19th century. That by [[Joseph Rodman Drake]], written before 1820, is a short lyric in octosyllabics with the message that shared suffering will lead to shared redemption beyond the grave. Though it carries the title "Abelard to Eloise" in a holographic copy,<ref>[http://www.abebooks.co.uk/Autograph-Transcription-poem-Abelard-Eloise-Drake/3386056076/bd Abe Books]</ref> it was also published without it after his death.<ref>[https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=p9oRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=%22weep+on+weep+on+we+wail+the+dead%22&source=bl&ots=0nJvVwhk-r&sig=ylrqLdZawjoS9Fzp--jVJ2sF4M4&hl=en&sa=X&ei=kIxQVcGnKYPSU8KageAH&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22weep%20on%20weep%20on%20we%20wail%20the%20dead%22&f=false ''The American Monthly Magazine'', Volume 6]</ref> The other two poems were more traditional. J. Treuwhard's ''Abelard to Eloisa, a moral and sentimental epistle'' was privately printed in 1830.<ref>Samuel Halkett, ''Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature'', New York 1926-34, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=EqvJftH0ggoC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=%22Abelard+to+Eloise%22&source=bl&ots=j7RQ2TbUt1&sig=ia60gjlETsSFF3xMeBZ8PCVl8PU&hl=en&sa=X&ei=21JQVeLAJce9UfHLgcAD&ved=0CCUQ6AEwATgK#v=onepage&q=%22Abelard%20to%20Eloise%22&f=false Volume 6, p.3]</ref>. The ''Epistle from Abelard to Eloise'', originally published in 1828 by Thomas Stewart (of Naples), was in heroic couplets and prefaced by a poem to Pope.<ref>''Napoleon's dying solioquy, and other poems'' (1834), [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Olv4P--gPQcC&pg=PA23&lpg=PA23&dq=Thomas+Stewart+of+Naples++if+in+these+realms&source=bl&ots=4g-oylvncM&sig=GFLZV37Lpdnk8pmuKwQDAELxM0U&hl=en&sa=X&ei=yZBQVdDzJ4KuUd-3gegO&ved=0CCMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Thomas%20Stewart%20of%20Naples%20%20if%20in%20these%20realms&f=false pp.21-38]</ref> |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist|2}} |

||

== |

==Bibliography== |

||

{{wikisource}} |

{{wikisource}} |

||

{{wikiquote}} |

{{wikiquote}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* John Hughes, [https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=A7pcAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false ''The Letters of Abelard and Heloise: with a particular account of their lives, amours, and misfortune''] Google Books |

|||

* [http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=5408 Literary Encyclopedia essay] |

* [http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=5408 Literary Encyclopedia essay] |

||

* [http://www.jmu.edu/writeon/documents/2001/brown.pdf "Castrating the Nun in Pope’s ''Eloisa to Abelard'' ”] (pdf) by Michelle L. Brown, James Madison University |

* [http://www.jmu.edu/writeon/documents/2001/brown.pdf "Castrating the Nun in Pope’s ''Eloisa to Abelard'' ”] (pdf) by Michelle L. Brown, James Madison University |

||

* [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/heloisedisc1.html Discussion of Heloise's Letters to Abelard], Fordham University |

* [http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/heloisedisc1.html Discussion of Heloise's Letters to Abelard], Fordham University |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [http://vitalpoetics.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Vitalpoetics-Vol1-No1-2008.pdf Eloisa and the Scene of Writing in Pope’s ''Eloisa to Abelard''], Vitalpoetics Vol. 1: 65-80. |

* [http://vitalpoetics.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Vitalpoetics-Vol1-No1-2008.pdf Eloisa and the Scene of Writing in Pope’s ''Eloisa to Abelard''], Vitalpoetics Vol. 1: 65-80. |

||

{{Alexander Pope}} |

{{Alexander Pope}} |

||

Revision as of 20:54, 11 May 2015

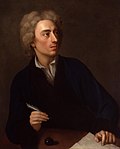

Published in 1717, Eloisa to Abelard is a poem by Alexander Pope (1688–1744). It is an Ovidian heroic epistle inspired by the 12th-century story of Héloïse d'Argenteuil's illicit love for, and secret marriage to, her teacher Peter Abelard, perhaps the most popular teacher and philosopher in Paris, and the brutal vengeance that her family exacts when they castrate him, even though the lovers had married.

After the assault, and even though they have a child, Abelard enters a monastery and bids Héloïse to do the same. She is tortured by the separation and by her unwilling vow of silence, which she takes with her eyes fixed upon Abélard rather than upon the cross (line 116).

Years later, Abelard completes Historia Calamitatum (History of My Misfortunes), which is a letter of consolation to a friend, and when it falls into her hands, her passion for him is reawakened. Héloïse and Abelard exchange four letters. In an effort to make sense of their personal tragedy, they explore the nature of human and divine love. However, their incompatible male and female perspectives make painful the dialogue for both.[1]

In Pope's poem, Eloisa is oppressed by the wild and gloomy landscape surrounding her convent and compares the happy state of “the blameless Vestal” with her own reliving of past passion and sorrow. She feels further anguish over the realization that Abelard, now a eunuch (which is a mercy that has freed him from the "contagion of carnal impurity"[2]), cannot return her feelings even if he wants to. And so she begs, not for forgiveness, but for forgetfulness.

- No, fly me, fly me, far as pole from pole;

- Rise Alps between us! and whole oceans roll!

- Ah, come not, write not, think not once of me,

- Nor share one pang of all I felt for thee.

And after death's release she looks forward to their sharing a single grave.[3]

Pope was born a Roman Catholic and so might be assumed to have a special interest and insight in the story. He had, however, a recently published source to inspire him and guide his readers. This was The Letters of Abelard and Heloise: with a particular account of their lives, amours, and misfortune, published by the poet John Hughes, which was first published in 1713 and was to go through many editions in the following century and more.[4]

Imitations and responses

The final lines of Pope's poem almost seem to invite a response from others:

- Such if there be, who love so long, so well,

- Let him our sad, our tender story tell;

- The well-sung woes will soothe my pensive ghost;

- He best can paint them who can feel them most.

Whether this was deliberate or not, some fourteen imitations of his poem had been written by the end of the century, all but one of them cast as Abelard's reply to Eloisa and written in heroic couplets. Although Pope's poem provided the main inspiration, and was frequently mentioned by the authors in their prefaces, there was always Hughes' volume with its historical account in the background. In later volumes the dependency between the two was further underlined by the inclusion first of Pope's poem in the Hughes volume (in the 1769 edition) and then some of the principal responses in following editions.

The poems in question are as follows:

- Abelard to Eloisa (1720) by Judith Madan.[5]

- Abelard to Eloisa (1725) by Petrus Abelardus [Richard Barford], “wherein we may observe how high we may raise the sentiments of our heart, when possessed of a great deal of wit and learning, with a most violent love”.

- Abelard to Eloisa (1726) by Richard Savage, prefaced by Pope's Eloisa to Abelard.[6]

- Abelard to Eloisa (1727) by William Pattison.[7]

- Abelard to Eloisa, in answer to Mr Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard (1730) by James Delacour(t).[8]

- Abelard to Eloisa (1747) by James Cawthorne (1719-1761).[9]

- Abelard to Eloisa by an unknown hand.[10]

- Abelard to Eloisa (1777) by St. John Drelincourt Seymour.[11]

- Abelard to Eloisa (1778) by Samuel Birch (1757-1841).[12]

- Eloisa en deshabille, being a new version of Mr Pope’s celebrated epistle (1780, with two later editions). In this a burlesque version in anapaestic measure appears opposite Pope's original. It has been ascribed to several authors, including Richard Porson, but is now thought to be by John Matthews.

- Eloisa to Abelard: an epistle, with a new account of their lives and references to their original correspondence (1785) by Thomas Warwick. This was an enlarged and corrected version of a work first published in 1882.

- Abelard to Eloisa by Edward Jerningham (1792). Also a Catholic, Jerningham gives a greater sense of the historical setting, especially the quarrel with Bernard of Clairvaux and Abelard's sentence of excommunication.

- A Struggle between Religion and Love, in an epistle from Abelard to Eloisa by Sarah Farrell (1792).[13]

- Abelard to Eloisa, in an early collection of poems by Walter Savage Landor (1795). In his preface, Landor discusses the difficulty of following Pope, but a commentator has suggested that he was also familiar with Hughes letters.[14]

Three of the poems above were written by young men of about 20: Pattison, Delacourt and Landor. Two women are included among the authors, of whom the earliest, Judith (Cowper) Madan, was a young disciple of Pope and published her poem before she was 20. Writing there from a male point of view, she matched Pope, who adopted a female identity in his poem.[15] Two later women also took up the subject. Christina Rossetti's "The Convent Threshold" (written in 1858) is, according to one source, “a thinly disguised retelling of Alexander Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard”,[16] although others are more cautious in seeing an influence. The poem is a surging monologue of enlaced rhymes in octosyllables, driving along its theme of leaving earthly passion behind and transmuting it to heavenly love.[17] The Australian writer Gwen Harwood went on to use the situation as a weapon in the gender war. Writing under the assumed name of Walter Lehmann in 1961, she placed two modernistic sonnets, "Eloisa to Abelard" and "Abelard to Eloisa", in a magazine without its editors realising that the letters of their first lines spelt an offensive message.[18]

Three more poems by males were written in the first half of the 19th century. That by Joseph Rodman Drake, written before 1820, is a short lyric in octosyllabics with the message that shared suffering will lead to shared redemption beyond the grave. Though it carries the title "Abelard to Eloise" in a holographic copy,[19] it was also published without it after his death.[20] The other two poems were more traditional. J. Treuwhard's Abelard to Eloisa, a moral and sentimental epistle was privately printed in 1830.[21]. The Epistle from Abelard to Eloise, originally published in 1828 by Thomas Stewart (of Naples), was in heroic couplets and prefaced by a poem to Pope.[22]

Notes

- ^ The Letters of Peter Abelard and Heloise, Augusta State University.

- ^ The Letters of Peter Abelard and Heloise, Letter 4, Augusta State University.

- ^ Lines 289-92

- ^ Google Books

- ^ Hughes, p.172ff

- ^ pp.119-150

- ^ In The Works of the British Poets vol.14, pp.419-424

- ^ Publishing information

- ^ Hughes, p.178ff

- ^ Hughes, p.189ff

- ^ Hughes p.205ff

- ^ Hughes, p.193ff

- ^ In Charlotte and other poems, pp.29-38

- ^ William Bradley, The early poems of Walter Savage Landor, pp.20-23

- ^ The Routledge Anthology of Cross-Gendered Verse, (2005)p.154

- ^ John Powell (ed), Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century, Greenwood Publishing 2001, p.348

- ^ Etext

- ^ Peter L. Shillingsburg, Resisting Texts: Authority and Submission in Constructions of Meaning, University of Michigan 1997, p.160, sonnets on p.161

- ^ Abe Books

- ^ The American Monthly Magazine, Volume 6

- ^ Samuel Halkett, Dictionary of Anonymous and Pseudonymous English Literature, New York 1926-34, Volume 6, p.3

- ^ Napoleon's dying solioquy, and other poems (1834), pp.21-38

Bibliography

- Alexander Pope, The Poetical Works Volume 1, Gutenberg Project

- John Hughes, The Letters of Abelard and Heloise: with a particular account of their lives, amours, and misfortune Google Books

- Literary Encyclopedia essay

- "Castrating the Nun in Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard ” (pdf) by Michelle L. Brown, James Madison University

- Discussion of Heloise's Letters to Abelard, Fordham University

- Eloisa and the Scene of Writing in Pope’s Eloisa to Abelard, Vitalpoetics Vol. 1: 65-80.