Modified gross national income: Difference between revisions

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

For example, Irish GNI was already 23% below Irish GDP before "[[leprechaun economics]]", however GNI* is only 30% below GDP (vs. expectation of closer to 40%).<ref name="ber">{{cite web|url=https://www.socialeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/p_imk_wp_175_2017.pdf|title=CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN OWNED COMPANIES |publisher=IMK Institute, Berlin|date=January 2017}}</ref><ref name="eurostat1"/><ref name="gni3">{{cite web|url=https://www.ft.com/content/dd3a6f1c-6aea-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa|title=Ireland's deglobalised data to calculate a smaller economy|publisher=Financial Times|date=17 July 2017}}</ref> |

For example, Irish GNI was already 23% below Irish GDP before "[[leprechaun economics]]", however GNI* is only 30% below GDP (vs. expectation of closer to 40%).<ref name="ber">{{cite web|url=https://www.socialeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/p_imk_wp_175_2017.pdf|title=CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN OWNED COMPANIES |publisher=IMK Institute, Berlin|date=January 2017}}</ref><ref name="eurostat1"/><ref name="gni3">{{cite web|url=https://www.ft.com/content/dd3a6f1c-6aea-11e7-bfeb-33fe0c5b7eaa|title=Ireland's deglobalised data to calculate a smaller economy|publisher=Financial Times|date=17 July 2017}}</ref> |

||

However, GNI* has now been adopted by the IMF and OECD in their Ireland reports.<ref |

However, GNI* has now been adopted by the IMF and OECD in their Ireland reports.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/11/10/Ireland-Technical-Assistance-Report-Public-Investment-Management-Assessment-45383|title=Ireland : Technical Assistance Report-Public Investment Management Assessment|publisher=IMF|date=November 2017}}</ref><ref name="oecd"/> |

||

The data issues remaining post "leprechaun economics", and "modified GNI", are captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:<ref name="oecd">{{cite web|url=http://www.finance.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/OECD-survey.pdf|title=OECD Ireland Survey 2018|publisher=OECD|date=March 2018}}</ref> |

The data issues remaining post "leprechaun economics", and "modified GNI", are captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:<ref name="oecd">{{cite web|url=http://www.finance.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/OECD-survey.pdf|title=OECD Ireland Survey 2018|publisher=OECD|date=March 2018}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 09:20, 12 April 2018

Modified GNI or also known as GNI* (or GNI star) was created by the Central Bank of Ireland in February 2017 as an improved way to measure the Irish economy, and Irish indebtedness, due to the increasing distortions that US "multinational tax schemes" were having on Irish GNI, Irish GNP and Irish GDP.

Irish GDP had inflated to 130% of Irish GNI (vs. 100% for EU-28), however the situation reached a crisis in October 2016 when the Irish CSO announced 2015 Irish GDP rose 26.3% and 2015 Irish GNP rose 18.7%, implying Irish GDP was over 150% of Irish GNI. This growth was due to Apple's 2015 restructuring of its Irish subsidiaries via a "capital allowances for intangibles assets" tax scheme. Noble-prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, called it "leprechaun economics".

The Central Statistics Office (Ireland) ("CSO") estimate 2016 Modified GNI (or GNI*) is 30% below 2016 Irish GDP (or, that Irish GDP is 143% of Irish GNI*).[1][2]

Original distortion

Irish economic data, and Irish GDP, in particular, has always been subject to caveats due to the tax planning activities of multinationals in Ireland. Tax planning "royalty payment" schemes like the famous "double Irish", create large flows that add to Irish GDP (especially), but do not incur material Irish taxes (if any).[3]

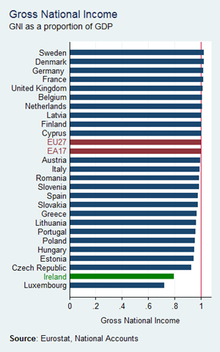

From the mid-2000s, US multinationals in Ireland (i.e. Microsoft), increased their use of the Irish "double Irish" tax avoidance scheme (see table opposite for Apple).[4] whose distortion manifests itself in deviations between Irish GDP and Irish GNI (EU28 countries have a GDP equal to GNI, see table)).

Artificially inflated Irish GDP (from US multinational tax plans), exaggerated the "Celtic Tiger" period by further stimulating both Irish consumer optimism (who increased borrowing to OCED record), and global capital markets optimism about Ireland (enabling Irish banks to borrow in excess of their deposits; reaching 180% by 2008[5]).[3]

This unwound in the economic crisis as global capital markets, who had ignored Ireland's worsening credit metrics (and OECD/IMF warnings) when Irish GDP was rising, suddenly took fright. Their withdrawal, from an over-borrowed Irish credit system, precipitated a deep Irish property and banking collapse in 2010-2012.[3][6]

The Irish economic collapse led to a material transfer of indebtedness from the Irish private sector balance sheet (most leveraged in the OECD with household debt-to-income of 190%), to the Irish public sector balance sheet (was almost unleveraged pre-crisis), via Irish bank bailouts and public deficit spending.[7][8] The ensuing EU-IMF-ECB (the Trokia) bailout of Ireland's public sector balance sheet required a debt-to-GDP de-leveraging plan, and Irish GDP distortion became an issue again.

Distortion restarts

As the US economy recovered, post the financial crisis, Ireland saw a large rise in US technology multinationals using the "double Irish" (i.e. Google, Apple and Facebook). By 2014, Apple's Irish subsidiary (ASI) was funnelling annual profits worth circa 20% of 2014 Irish GNI (see table).

In addition, 2009-2015 saw a large rise in US corporate tax inversions (mainly of pharmaceutical and medical device firms), who also have an equally minimal contribution to Ireland's taxable base, but a material effect on the Irish national accounts).[9] (see Irish corporate tax inversions).

By 2016, the top 20 Irish companies (by Irish turnover) were dominated by US technology multinationals and US corporate tax inversions:[10]

Over 80% of Ireland's corporate tax payments from 2010-2016,[11] and from 2016 alone,[12] came from foreign owned multinationals based in Ireland.[13]

By 2016, the OECD estimated that foreign multinationals employed almost one quarter of the Irish private sector labour force in 2013.[14]

This rise in multinationals in Ireland, of which 80% are US-owned,[15][16] accelerated the distortion in Irish economic statistics.

By 2011, Ireland's ratio of GNI to GDP, had fallen to 80% (i.e. Irish GDP was 125% of Irish GNI). Only Luxembourg was lower at 73% (i.e. Luxembourg GDP is 137% of Luxembourg GNI). As the GNI/GDP table (see opposite) shows, EU GDP is circa 100% of EU GNI for almost every other country in the European Union (and for the EU28 average).[3][17]

A 2015 EU Commission report showed that from 2010 to 2015, almost 23% of Ireland's GDP was now represented by untaxed multinational net royalty payments (implying that Irish GDP was now circa 130% of Irish GNI).[18] This was raising concern in the EU-IMF-ECB (the Trokia), over Ireland's true indebtedness position.[19][20]

The Irish financial media were also confused as to Ireland’s state of indebtedness as debt-per-capita diverged sharply from debt-to GDP.[21][22][23][24]

2016 Distortion climax

The distortion of Irish GNI/GNP/GDP came to a climax when Apple restructured its controversial ASI subsidiary (which EU Commission had judged as receiving illegal Irish State Aid) in January 2015, and brought it "onshore" to Ireland via a new Irish "capital allowances for intangible assets" scheme.[4]

The Irish “capital allowances for intangible assets” schemes are more distorting than the traditional “double Irish”-type schemes, as the "royalty payment" effect is capitalised or front-loaded. They present as quasi-"corporate tax inversions" in the Irish national accounts.

Apple's restructuring led to 2015 Irish economic growth rates of 26.3% (GDP) and 18.7% (GNP) respectively, announced by the CSO in July 2016.[25]

This led to widespread Irish and International riducle,[26][27][28][29][29][30][31][32] and was labelled by Noble Prize economist Paul Krugman as "leprechaun economics".[33]

The situation was not helped by the fact that neither the CSO nor the Department of Finance, would specifically identify the source of such a large rise.[34] The explanation provided changed over the course of the two weeks after it was released[35] (it wasn't until 2018 that Apple could be definitively proven as the source[4]).

Markets saw Finance Minister Michael Noonan "pay" €380m in additional annual EU GDP levies[36][37] (he had made Apple's 2015 new Irish "capital allowance" scheme free of Irish taxes in the 2015 Budget by lifting the cap to 100%),[38] to generate "artificial" increases in the Irish GDP, GNP and GNI economic statistics.

His predessor, Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe immediately reversed the 2015 Budget cap reduction to ensure that "capital allowances" schemes would at least pay effective Irish corporate tax rates of 2-3% (by reducing the cap on relief back to 80% from Noonan's 100% level). However, he only applied this to new schemes.[38]

While financial markets had always been wary of Irish economic data, Noonan's actions severally damaged their confidence.[39]

2017 GNI* response

In response to these issues, and as a direct result of the "leprechaun economics" affair, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland ("CBI"), Philip R. Lane, convened a special cross economic steering group (the Economic Statistics Review Group, or "ESRG") of major stakeholders (incl. CBI, IFAC, ESRI, NTMA, leading academics and the Department of Finance), in September 2016, to recommend new economic statistics to the Central Statistics Office ("CSO"), that would better represent the true position of the Irish economy.[40]

The result was the creation of a new metric - "modified Gross National Income" (or GNI* for short). The difference between GNI* and GNI is due to having to deal with two problems (a) The retained earnings of re-domiciled firms in Ireland (where the earnings ultimately accrue to foreign investors), and (b) depreciation on foreign-owned capital assets located in Ireland, such as intellectual property (which inflate the size of Irish GDP, but again the benefits accrue to foreign investors). Report Site of the ESRG.[41][42]

The CSO simplify the definition of Irish modified GNI (or GNI*) as:

Irish GNI less the effects of the profits of re-domiciled companies and the depreciation of intellectual property products and aircraft leasing companies.[43]

The CSO will continue to calculate and release Irish GDP and Irish GNP to meet their EU and other International statistical reporting commitments.[44]

The CSO estimated that 2016 Irish GNI* (€190bn) is 30% below 2016 Irish GDP (€275bn) and Irish Net Public Debt/GNI* goes to 106% (Irish Net Public Debt/GDP was 73%).[1][2]

2018 Debt metrics

A key driver for the creation of the "modified GNI" (or GNI*) was around providing global capital providers (including the ECB and IMF), with appropriate Irish debt metrics.

Commentators (including Eurostat[45]) noted that GNI* was very helpful, but still did not remove all the effects of multinational tax planning.[3][45][46][47][48][49]

For example, Irish GNI was already 23% below Irish GDP before "leprechaun economics", however GNI* is only 30% below GDP (vs. expectation of closer to 40%).[3][45][50]

However, GNI* has now been adopted by the IMF and OECD in their Ireland reports.[51][52]

The data issues remaining post "leprechaun economics", and "modified GNI", are captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:[52]

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern.

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming.

- On a Gross Public Debt Per Capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at over $62,686 per capita, exceeds every other OECD country, except Japan.[53]

Irish financial commentators are concerned that Ireland repeats the mistakes of the "Celtic Tiger" era, and over leverages again, against distorted Irish economic statistics.[46]

Also, given the transfer of Irish private sector debt to the Irish public balance sheet from the crisis, it will not be possible to re-bail out the Irish banking system again.

- The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council introduced another established measure for benchmarking Irish public debt by comparing to Irish Tax Revenues (similar to the Debt-to-EBITDA ratio used in capital markets). On this basis, Ireland's 2016 Gross Public Debt-to-Tax Revenues is 282.9%, which is the 4th highest of the EU-28 (after Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus).[54][55][56]

- The Central Bank of Ireland has also followed the ECB's focus on "disposable income" when benchmarking Irish private debt. As with 2016 Irish public debt, 2016 Irish private debt as a % of Irish disposable income, is one of the highest ratios in the EU-28 with household debt-to-disposable income at 141.6% (4th behind Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden).[57][58]

However, the above two examples show that Ireland's high public debt levels and high private sector debt levels, imply that on a "total debt" basis (i.e. public plus private), Ireland is likey the most indebted of the EU28 countries (when benchmarked on a GNI*-type basis). Therefore using "modified GNI" (or GNI*), will be imporatant in tracking this metric.

See also

- Double Irish, Single Malt, Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets

- Economy of the Republic of Ireland

- Corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland

- Irish Fiscal Advisory Council

- Revenue Commissioners

- Central Bank of Ireland

- Central Statistics Office (Ireland)

References

- ^ a b "CSO paints a very different picture of Irish economy with new measure". Irish Times. 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b "New economic Leprechaun on loose as rate of growth plunges". Irish Independent. 15 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN OWNED COMPANIES" (PDF). IMK Institute, Berlin. January 2017.

- ^ a b c "What Apple did next". Seamus Coffey, University College Cork. 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Irish Banks continue to grow deposits as loan books shrink". Irish Examiner. December 2012.

- ^ "IRELAND FINANCIAL SYSTEM STABILITY ASSESSMENT 2016" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. July 2016.

- ^ "Irish government debt four times pre-crisis level, NTMA says". 10 July 2017.

- ^ "42% of Europe's banking crisis paid by Ireland". 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Effect of Redomiciled PLCs". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). July 2017.

- ^ "Ireland's Top 1000 Companies". Irish Times. 2018.

- ^ "20 multinationals paid half of all Corporation tax paid in 2016". RTE News. 21 June 2017.

- ^ "An Analysis of 2015 Corporation Tax Returns and 2016 Payments" (PDF). Revenue Commissioners. April 2017.

- ^ "Most of Ireland's huge corporate tax haul last year came from foreign firms". sunday Business Post FORA. 14 May 2016.

- ^ "IRELAND Trade and Statistical Note 2017" (PDF). OECD. 2017.

- ^ "Corporate Tax regime in Ireland". Industrial Development Authority (IDA). 2018.

- ^ "Corporate Taxation in Ireland 2016" (PDF). Industrial Development Authority (IDA). 2018.

- ^ "International GNI to GDP Comparisons". Seamus Coffey, University College Cork. 29 April 2013.

- ^ "Europe points finger at Ireland over tax avoidance". Irish Times. 7 March 2018.

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics': EU mission to audit 26% GDP rise". Irish Times. 19 August 2016.

- ^ "Economic Dialogue with Ireland Box 1: GDP statistics in Ireland: "Leprechaun economics"?" (PDF). EU Commission. 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Who owes more money - the Irish or the Greeks?". Irish Times. 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Why do the Irish still owe more than the Greeks?". Irish Times. 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Ireland's colossal level of indebtedness leaves any new government with precious little room for manoeuvre". Irish Independent. 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Net National debt now €44000 per head, 2nd highest in the World". Irish Independent. 7 July 2017.

- ^ "National Income and Expenditure Annual Results 2015". Central Statistics. 12 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics' - Ireland's 26pc growth spurt laughed off as 'farcical'". Irish Independent. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Concern as Irish growth rate dubbed 'leprechaun economics'". Irish Times. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Blog: The real story behind Ireland's 'Leprechaun' economics fiasco". RTE News. 25 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Irish tell a tale of 26.3% growth spurt". Financial Times. 12 July 2016.

- ^ ""Leprechaun economics" - experts aren't impressed with Ireland's GDP figures". thejournal.ie. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun economics' leaves Irish growth story in limbo". Reuters News. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun Economics' Earn Ireland Ridicule, $443 Million Bill". Bloomberg News. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Leprechaun Economics". Paul Krugman (Twitter). 12 July 2016.

- ^ "'Leprechaun Economics' not all down to Apple move, insists CSO". Irish Independent. 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Economy grew by 'dramatic' 26% last year after considerable asset reclassification". RTE News. 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Now 'Leprechaun Economics' puts Budget spending at risk". Irish Independent. 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Leprechaun economics pushes Ireland's EU bill up to €2bn". Irish Independent. 30 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Change in tax treatment of intellectual property and subsequent and reversal hard to fathom". Irish Times. 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Meaningless economic statistics will cause problems for stewardship of country". RTE News. 13 July 2016.

- ^ "REPORT OF THE ECONOMIC STATISTICS REVIEW GROUP" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. December 2016.

- ^ "ESRG Presentation and CSO Response" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. 4 February 2017.

- ^ "Leprechaun-proofing economic data". RTE News. 4 February 2017.

- ^ "CSO Data Editor's Note". Central Statistics Office. 14 July 2017.

- ^ "Central Statistics Office (CSO) Response to the Main Recommendations of the Economic Statistics Review Group (ESRG)" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. 3 February 2017.

- ^ a b c "Globalisation at work in statistics — Questions arising from the 'Irish case'" (PDF). EuroStat. December 2017.

- ^ a b "Ireland's economic figures still not adding up". Irish Times. January 2017.

- ^ "What is going on with GNP (again)?". Seamus Coffey, University College Cork. 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Lies, damned lies and the national accounts headline figures". The Irish Times. 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Column: The Leprechauns are at it again in the latest GDP figures for Ireland". thejournal.ie. 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Ireland's deglobalised data to calculate a smaller economy". Financial Times. 17 July 2017.

- ^ "Ireland : Technical Assistance Report-Public Investment Management Assessment". IMF. November 2017.

- ^ a b "OECD Ireland Survey 2018" (PDF). OECD. March 2018.

- ^ "National debt now €44000 per head". Irish Independent. 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Debt levels remain high following the crisis June FAR Slide 7" (PDF). Irish Fiscal Advisory Council. June 2017.

- ^ "Section 1.2.2 Recent Fiscal Context June FAR Page 14" (PDF). Irish Fiscal Advisory Council. June 2017.

- ^ "Future Implications of the Debt Rule" (PDF). Irish Fiscal Advisory Council. June 2014.

- ^ "Quarterly Statistical Release November 2017" (PDF). Central Bank of Ireland. November 2017.

- ^ "Household debt now at its lowest level since 2005". Irish Independent. 7 November 2017.