Curule seat: Difference between revisions

m robot Removing: zh:資格座椅 |

citation for an assertion; gilded, not "of gold" |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Image:Aureus Macrinus-RIC 0079.jpg|thumb|right|[[Macrinus]] on an [[aureus]]. On the reverse, the emperor and his son are sitting on their ''curule chairs''.]] |

[[Image:Aureus Macrinus-RIC 0079.jpg|thumb|right|[[Macrinus]] on an [[aureus]]. On the reverse, the emperor and his son are sitting on their ''curule chairs''.]] |

||

According to [[Livy]] the '''curule |

According to [[Livy]] the '''curule seat''' ('''''sella curulis''''', supposedly from ''currus'', "chariot") originated in [[Etruria]], and it has been identified used on surviving Etruscan monuments to identify magistrates,<ref>Thomas Schäfer, ''Imperii insignia: Sella Curulis und Fasces. Zur Repräsentation römischer Magistrate'', (Mainz) 1989, fully discusses the representations of curule seats and their evolving significance.</ref> but earlier stools supported on a cross-frame are known from the [[New Kingdom of Egypt]]. |

||

In the [[Roman Republic]], and later the Empire, the curule |

In the [[Roman Republic]], and later the Empire, the curule seat was the chair upon which senior magistrates or promagistrates owning ''[[imperium]]'' were entitled to sit, including [[dictator]]s, [[Master of the Horse|masters of the horse]], [[consul]]s, [[praetor]]s, [[Roman censor|censor]]s, and the [[curule aedile]]s. Additionally, the [[Flamen]] of [[Jupiter (god)|Iuppiter]] (Flamen Dialis) was also allowed to sit on a ''sella curulis,'' though this position lacked ''imperium''. According to [[Cassius Dio]], early in 44 BCE a senate decree granted [[Julius Caesar]] the sella curulis everywhere except in the theatre, where his [[gilding|gilded]] chair and jeweled crown were carried in, putting him on a par with the gods.<ref>Peter Michael Swan, ''The Augustan Succession: An historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History Books 55-56 (9 B.C.-A.D. 14)'', "Commentary on Book 56", (Oxford 2004) p. 298, noting T. Schäfer 1989, pp 114-22.</ref> |

||

The curule chair is used on Roman medals as well as funerary monuments to express a curule magistracy; when traversed by a [[Hasta (spear)|hasta]] (spear), it is the symbol of [[Juno (mythology)|Juno]], and serves to express the conservation of princesses.<!--"conservation of princesses" is a strange term in a Roman context--><ref>{{1728}}</ref> |

The curule chair is used on Roman medals as well as funerary monuments to express a curule magistracy; when traversed by a [[Hasta (spear)|hasta]] (spear), it is the symbol of [[Juno (mythology)|Juno]], and serves to express the conservation of princesses.<!--"conservation of princesses" is a strange term in a Roman context--><ref>{{1728}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:32, 5 February 2009

According to Livy the curule seat (sella curulis, supposedly from currus, "chariot") originated in Etruria, and it has been identified used on surviving Etruscan monuments to identify magistrates,[2] but earlier stools supported on a cross-frame are known from the New Kingdom of Egypt.

In the Roman Republic, and later the Empire, the curule seat was the chair upon which senior magistrates or promagistrates owning imperium were entitled to sit, including dictators, masters of the horse, consuls, praetors, censors, and the curule aediles. Additionally, the Flamen of Iuppiter (Flamen Dialis) was also allowed to sit on a sella curulis, though this position lacked imperium. According to Cassius Dio, early in 44 BCE a senate decree granted Julius Caesar the sella curulis everywhere except in the theatre, where his gilded chair and jeweled crown were carried in, putting him on a par with the gods.[3]

The curule chair is used on Roman medals as well as funerary monuments to express a curule magistracy; when traversed by a hasta (spear), it is the symbol of Juno, and serves to express the conservation of princesses.[4]

The curule chair was traditionally made of or veneered with ivory, with curved legs forming a wide X; it had no back, and low arms. The chair could be folded, and thus an easily transportable seat, originally for magisterial and promagisterial commanders in the field, developed a hieratic significance, expressed in fictive curule seats on funerary monuments, a symbol of power which was never entirely lost in post-Roman European tradition.[5] Sixth-century consular ivory diptychs of Orestes and of Constantinus each depict the consul seated on an elaborate curule seat with crossed animal legs.[6]

In Gaul the Merovingian successors to Roman power employed the curule seat as an emblem of their right to dispense justice, and their Capetian successors retained the iconic seat: the "Throne of Dagobert", of cast bronze retaining traces of its former gilding, is conserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The "throne of Dagobert" is first mentioned in the twelfth century, already as a treasured relic, by Abbot Suger, who claims in his Administratione, "We also restored the noble throne of the glorious King Dagobert, on which, as tradition relates, the Frankish kings sat to receive the homage of their nobles after they had assumed power. We did so in recognition of its exalted function and because of the value of the work itself." Abbot Suger added bronze upper members with foliated scrolls and a back-piece. The "Throne of Dagobert" was coarsely repaired and used for the coronation of Napoleon.[7]

In the fifteenth century, a characteristic folding-chair of both Italy and Spain was made of numerous shaped cross-framed elements, joined to wooden members that rested on the floor and further made rigid with a wooden back. Nineteenth-century dealers and collectors termed these "Dante Chairs" or "Savonarola Chairs", with disregard to intervening centuries between the teo figures. Examples of curule seats were redrawn from a fifteenth-century manuscript of the Roman de Renaude de Montauban and published in Henry Shaw's Specimens of Ancient Furniture (1836).[8]

The fifteenth or early sixteenth-century curule seat at York Minster, originally entirely covered with textiles, has rear members extended upwards to form a back, between which a rich textile was stretched. Similar early seventeenth-century cross-framed seats survive at Knole, perquisites from a royal event.[9]

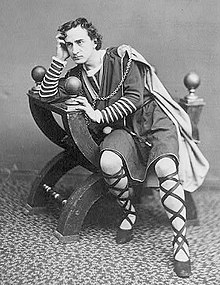

The photo of actor Edwin Booth as Hamlet (illustration) poses him in a regal cross-framed chair, considered suitably medieval in 1870.

The form found its way into stylish but non-royal decoration in the archaeological second phase of neoclassicism in the early 19th century. An unusually early example of this revived form is provided by the example of large sets of richly carved and gilded pliants (folding stools) forming part of long sets with matching tabourets delivered in 1786 to the royal châteaux of Compiègne and Fontainebleau.[10] With their Imperial Roman connotations, the backless curule seats found their way into furnishings for Napoleon, who moved some of the former royal pliants into his state bedchamber at Fontainebleau. Further examples were ordered, in the newest Empire taste: Jacob-Desmalter's seats with members in the form of carved and gilded sheathed sabres were delivered to Saint-Cloud about 1805.[11] Cross-framed drawing-room chairs are illustrated in Thomas Sheraton's last production, The Cabinet-Maker, Upholsterer and General Artist's Encyclopaedia (1806), and in Thomas Hope's Household Furniture (1807).

Notes

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Thomas Schäfer, Imperii insignia: Sella Curulis und Fasces. Zur Repräsentation römischer Magistrate, (Mainz) 1989, fully discusses the representations of curule seats and their evolving significance.

- ^ Peter Michael Swan, The Augustan Succession: An historical Commentary on Cassius Dio's Roman History Books 55-56 (9 B.C.-A.D. 14), "Commentary on Book 56", (Oxford 2004) p. 298, noting T. Schäfer 1989, pp 114-22.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Schäfer 1989.

- ^ Discussed and illustrated in Nancy Netzer, "Redating the Consular Ivory of Orestes" The Burlington Magazine 125 No. 962 (May 1983): 265-271) p. 267, figs. 11-13.

- ^ Sir W. Martin Conway, The Treasures of Saint Denis, 1915

- ^ Some are illustrated in John Gloag, A Short Dictionary of Furniture, rev. ed. 1969: s.v. "X-chairs".

- ^ The contemporary term "cross-framed" came to be employed in the later seventeenth century to describe chairs with horizontal cross-framed stretchers, possibly causing confusion for a modern reader; see Adam Bowett, "The English 'Cross-Frame' Chair, 1694-1715" The Burlington Magazine 142 No. 1167 (June 2000:344-352).

- ^ Pierre Verlet, French Royal Furniture p. 75f; F.J.B. Watson, The Wrightsman Collection (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 1966:vol. I, cat. no. 51ab, pp76-78.

- ^ One at the Victoria and Albert Museum is illustrated in Serge Grandjean, Empire Furniture, (London: Faber and Faber) 1966:fig. 7. Grandjean also illustrates a gilded curule seat from the former Grand Galerie, Malmaison, ca 1804 (fig. 5b); a painted one from Fontainebleau (fig. 31), and a walnut curule seat in Empire style, from Romagna (fig. 6).