Starfish: Difference between revisions

Apokryltaros (talk | contribs) m Undid revision 128023767 by 207.255.18.251 (talk) |

|||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

Some echinoderms have been shown to live for several weeks without food under artificial conditions—it is believed that they may receive some nutrients from organic material dissolved in seawater. |

Some echinoderms have been shown to live for several weeks without food under artificial conditions—it is believed that they may receive some nutrients from organic material dissolved in seawater. |

||

Sea stars and other echinoderms have endoskeletons (internal skeletons), which is one of the reasons some scientists are led to beleive that echinoderms are very cosely related to chordates (animals with a hollow nerve chord that usually have vertebrae). |

|||

===Nervous system=== |

===Nervous system=== |

||

Revision as of 21:31, 3 May 2007

| Starfish | |

|---|---|

| |

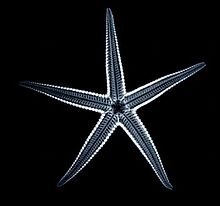

| "Asteroidea" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Asteroidea

|

| Orders | |

|

Forcipulatida | |

Starfish (more correctly known as sea stars as they are only very distantly related to fish), are marine invertebrates belonging to the kingdom animalia, phylum Echinodermata, class Asteroidea. The names sea star and starfish are also (incorrectly) used for the closely related brittle stars, which make up the class Ophiuroidea. They exhibit a superficially radial symmetry. Starfish typically have five or more "arms" which radiate from an indistinct disk (pentaradial symmetry). In fact, the evolutionary ancestors of echinoderms are believed to have had bilateral symmetry, and starfish do exhibit some superficial remnant of this body structure, which is evident in their larval pluteus forms. Starfish do not rely on a jointed, movable skeleton for support and locomotion (though they are protected by their skeleton), but instead possess a hydraulic water vascular system that aids in locomotion. The water vascular system has many projections called tube feet, located on the ventral face of the starfish's arms, which function in locomotion and aid with feeding.

Distribution

There are about 1,800 living species of starfish, and they occur in all of the Earth's oceans. The greatest variety of starfish is found in the tropical Indo-Pacific. Areas known for their great diversity include the tropical-temperate regions around Australia, the tropical East Pacific, and the cold-temperate water of the North Pacific (California to Alaska). Asterias is a common genus found in European waters and on the eastern coast of the United States; Pisaster, along with Dermasterias ("leather star"), are usually found on the western coast. Habitats could range from tropical coral reefs, kelp forests to deep-sea floor, although none of them live within the water column; all species of starfish found are living as benthos. Echinoderms need a delicate internal balance in their body; no starfish are found in freshwater environments.

External anatomy

Starfish are composed of a central disc from which arms sprout in pentaradial symmetry. Most starfish have five arms, however some have more or less; in fact some starfish can have different numbers of arms even within one species. The mouth is located underneath the starfish on the oral or ventral surface, while the anus is located on the top of the animal. The spiny upper surface covering the species is called the aboral or dorsal surface. On the aboral surface there is a structure called the madreporite, which acts as a water filter and supplies the starfish's water vascular system with water to move. Additional parts like cribriform organs present exclusively in Porcellanasteridae are used to generate current in the burrows made by these infaunal starfish.

Starfish, while having their own basic body plan, radiate diversely in shapes and colors and the morphology differs between each species; for example, a species of starfish may have rows of spines on their arms as means of protection. Ranging from nearly pentagonal (example: Indo-pacific cushion star, Culcita novaeguineae) to gracile stars like those on Zoroaster genus.

Starfish have a simple photoreceptor eyespot at the end of each arm. The eye is able to "see" only differences of light and dark, which is useful in detecting movement.

On the surface of the starfish, surrounding the spines, are small white objects known as pedicellariae. There are large numbers of these pedicellariae on the external body which serve to prevent encrusting organisms from colonizing the starfish. The radial canal which is across each arm of the starfish has tooth-like structures called ampullae, which surround the radial canal. The aboral surface is aell. Patterns including mosaic-like tiles formed by ossicles, stripes, interconnecting net between spines, pustules with bright colors, mottles or spots. These mainly serve as camouflage or warning coloration displayed by many other marine animals as means of protection against predation. Several types of toxins and secondary metabolites have been extracted from several species of starfish and now being subjected into research worldwide for pharmacy or other uses such as pesticides.

Internal anatomy

The body cavity also contains the water vascular system that operates the tube feet, and the circulatory system, also called the hemal system. Hemal channels form rings around the mouth (the oral hemal ring), closer to the top of the starfish and around the digestive system (the gastric hemal ring). The axial sinus, a portion of the body cavity, connects the three rings. Each ray also has hemal channels running next to the gonads.

Digestion and excretion

Starfish digestion is carried out in two separate stomachs. They are called the cardiac stomach and the pyloric stomach. The cardiac stomach, which is a sack like stomach located at the center of the body may be everted—pushed out of the organism's body and used to engulf and digest food. Some species take advantage of the great endurance of their water vascular systems to force open the shells of bivalve mollusks such as clams and mussels, and inject their stomachs into the shells. Once the stomach is inserted inside the shell it digests the mollusk in place. The cardiac stomach is then brought back inside the body, and the partially digested food is moved to the pyloric stomach. Further digestion occurs in the intestine and waste is excreted through the anus on the aboral side of the body.

Because of this ability to digest food outside of its body, the sea star is able to hunt prey that are much larger than its mouth would otherwise allow including arthropods, and even small fish in addition to mollusks.

Some echinoderms have been shown to live for several weeks without food under artificial conditions—it is believed that they may receive some nutrients from organic material dissolved in seawater.

Sea stars and other echinoderms have endoskeletons (internal skeletons), which is one of the reasons some scientists are led to beleive that echinoderms are very cosely related to chordates (animals with a hollow nerve chord that usually have vertebrae).

Nervous system

Echinoderms have rather complex nervous systems, but lack a true centralized brain. All echinoderms have a nerve plexus (a network of interlacing nerves), which lies within as well as below the skin. The esophagus is also surrounded by a number of nerve rings, which send radial nerves that are often parallel with the branches of the water vascular system. The ring nerves and radial nerves coordinate the starfish's balance and directional systems. Although the echinoderms do not have many well-defined sensory inputs, they are sensitive to touch, light, temperature, orientation, and the status of water around them. The tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae found on starfish are sensitive to touch, while eyespots on the ends of the rays are light-sensitive.

Behavior

Diet

Most species are generalist predators, some eating bivalves like mussels, clams, and oysters; or any animal too slow to evade the attack (e.g. dying fish). Some species are detritivores, eating decomposed animal and plant material, or organic films attached to substrate. The others may consume coral polyps (the best-known example for this is the infamous Acanthaster planci), sponges or even suspended particles and planktons (starfish from the Order Brisingida). The process of feeding or capture may or may not be aided by special parts; Pisaster brevispinus or Short-spined Pisaster from the west coast of America may use a set of specialized tube feet capable of extending itself deep into the soft substrata, hauling out the prey (usually clams) from within[1].

Reproduction

Starfish are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction. Individual starfish are male or female. Fertilization takes place externally, both male and female releasing their gametes into the environment. Resulting fertilized embryos form part of the zooplankton.

Starfish are developmentally (embryologically) known as deuterostomes. Their embryo initially develops bilateral symmetry, indicating that starfish probably share a common ancestor with the chordates, which includes the fish. Later development takes a very different path however as the developing starfish settles out of the zooplankton and develops the characteristic radial symmetry. Some species reproduce cooperatively, using environmental signals to coordinate the timing of gamete release; in other species, one to one pairing is the norm.

Some species of starfish also reproduce asexually by fragmentation, often with part of an arm becoming detached and eventually developing into an independent individual starfish. This has led to some notoriety. Starfish can be pests to fishermen who make their living on the capture of clams and other mollusks at sea as starfish prey on these. The fishermen would presumably kill the starfish by chopping them up and disposing of them at sea, ultimately leading to their increased numbers until the issue was better understood. A starfish arm can only regenerate into a whole new organism if some of the central ring of the starfish is part of the chopped off arm.

Locomotion

Starfish move using a water vascular system. Water comes into the system via the madreporite. It is then circulated from the stone canal to the ring canal and into the radial canals. The radial canals carry water to the ampullae and provide suction to the tube feet. The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one body section attaching to the surfaces as another releases. Most starfish cannot move quickly. However, some burrowing species like starfish from genus Astropecten and Luidia are quite capable of rapid, creeping motion - it "glides" across the ocean floor. This motion results from their pointed tubefeet adapted specially for excavating local area of sand.

Regeneration

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new arm in time. Most species must have the central part of the body intact to be able to regenerate, but a few can grow an entire starfish from a single ray. Included in this group are the red and blue Linckia star. The regeneration of these stars is possible due to the vital organs kept in their arms.

Geological history

Fossil starfish and brittle stars are first known from rocks of Ordovician age indicating that two groups probably diverged in the Cambrian. However, Ordovician examples of the two groups show many similarities and can be difficult to distinguish. Complete fossil starfish are very rare, but where they do occur they may be abundant. Most fossil starfish consist of scattered individual plates or segments of arms. This is because the skeleton is not rigid, as in the case of echinoids (sea urchins), but is composed of many small plates (or ossicles) which quickly fall apart and are scattered after death and the decay of the soft parts of the creature. Scattered starfish ossicles are reasonably common in the Cretaceous Chalk Formation of England.

See also

- Asterias

- Acanthaster planci

- Linckia laevigata

- Platanaster (extinct genus)

- Protoreaster nodosus

- Ophiuroidea (brittle stars)

References

- ^ Nybakken Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach, Fourth Edition, page 174. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc., 1997.

- Blake DB, Guensburg TE; Implications of a new early Ordovician asteroid (Echinodermata) for the phylogeny of Asterozoans; Journal of Paleontology, 79 (2): 395-399; MAR 2005.

- Gilbertson, Lance; Zoology Lab Manual; McGraw Hill Companies, New York; ISBN 0-07-237716-X (fourth edition, 1999).

- Shackleton, Juliette D.; Skeletal homologies, phylogeny and classification of the earliest asterozoan echinoderms; Journal of Systematic Palaeontology; 3 (1): 29-114; March 2005.

- Solomon, E.P., Berg, L.R., Martin, D.W. 2002. Biology, Sixth Edition.

- Sutton MD, Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Gladwell DJ; A starfish with three-dimensionally preserved soft parts from the Silurian of England; Proceedings of the Royal Society B - Biological Sciences; 272 (1567): 1001-1006; MAY 22 2005.

- Hickman C.P, Roberts L.S, Larson A., l'Anson H., Eisenhour D.J.; Integrated Principles of Zoology; McGraw Hill; New York; ISBN 0-07-111593-5 (Thirteenth edition; 2006).

Resources

- Starfish Science

- From the Tree of Life project

- Classification of the Extant Echinodermata

- Starfish Home Page

- Starfish Population Explosion

- Beautiful story - The Legend of the Starfish