IS–LM model: Difference between revisions

→Formulation: fixes |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Formulation== |

==Formulation== |

||

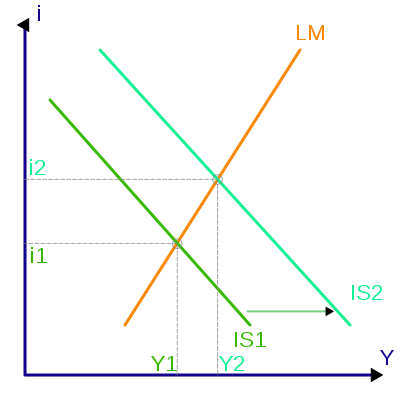

The model is presented as a graph of two intersecting lines in the first quadrant. |

|||

The horizontal axis represents [[national income]] or [[real vs. nominal in economics|real]] [[gross domestic product]] and is labelled '''''Y'''.'' The vertical axis represents the real [[interest]] rate, '''''i'''.'' |

The horizontal axis represents [[national income]] or [[real vs. nominal in economics|real]] [[gross domestic product]] and is labelled '''''Y'''.'' The vertical axis represents the real [[interest]] rate, '''''i'''.'' |

||

Revision as of 21:54, 30 October 2007

The IS/LM model, first developed by Sir John Hicks and Alvin Hansen, has been used from 1937 onwards to summarize a major part of Keynesian macroeconomics.

Formulation

The model is presented as a graph of two intersecting lines in the first quadrant.

The horizontal axis represents national income or real gross domestic product and is labelled Y. The vertical axis represents the real interest rate, i.

The IS schedule is drawn as a downward-sloping curve. The initials IS stand for "Investment/Saving equilibrium" but since 1937 have been used to represent the locus of all equilibria where total spending (Consumer spending + planned private Investment + Government purchases + net exports) equals an economy's total output (equivalent to income, Y, or GDP). To keep the link with the historical meaning, the IS curve can represent the equilibria where total private investment equals total saving, where the latter equals consumer saving plus government saving (the budget surplus) plus foreign saving (the trade surplus). Either way, in equilibrium, all spending is desired or planned; there is no unplanned inventory accumulation (i.e., no general glut of goods and services).[1] The level of real GDP (Y) is determined along this line for each interest rate.

Thus the IS schedule is a locus of points of equilibrium in the "real" (non-financial) economy. Given expectations about returns on fixed investment, every level of interest rate (i) will generate a certain level of planned fixed investment and other interest-sensitive spending: lower interest rates encourage higher fixed investment and the like. Income is at the equilibrium level for a given interest rate when the saving consumers choose to do out of that income equals investment (or, more generally, when "leakages" from the circular flow equal "injections"). A higher level of income is needed to generate a higher level of saving (or leakages) at a given interest rate. Alternatively, the multiplier effect of an increase in fixed investment raises real GDP. Both ways explain the downward slope of the IS schedule. In sum, this line represents the line of causation from falling interest rates to rising planned fixed investment (etc.) to rising national income and output.

The LM schedule is an upward-sloping curve representing the role of finance and money. The initials LM stand for "Liquidity preference/Money supply equilibrium" but is easier to understand as the equilibrium of the demand to hold money (as an asset and for use in everyday transactions) and the supply of money by banks and the central bank. The interest rate is determined along this line for each level of real GDP.

In a closed economy, the IS curve is defined as: Y=C(Y-T)+I(r)+G, where Y represents income, C(Y-T) represents consumer spending as a function of disposable income (income, Y, minus taxes, T), I(r) represents investment as a function of the real interest rate, and G represents government spending. In this equation, the level of G (government spending) and T (taxes) are presumed to be exogenous, meaning that they are taken as a given. In a similar fashion, the LM curve is defined as M/P=L(r,Y), where the supply of money is represented as the real money balance M/P (as opposed to the nominal balance M), with P representing a price deflator, equals the demand for money L, which is some function of the interest rate and the level of income. To adapt this model to an open economy, a term for net exports (exports, X, minus imports, M) would need to be added to the IS equation. An economy with more imports than exports would have a negative net exports number.

Rising GDP (Y) implies an increased transactions demand for money and liquidity preference. With a given and inelastic money supply curve, the equilibrium interest rate (i) rises. This explains the upward slope of the LM curve.

The point where these schedules intersect represents a short-run equilibrium in the real and monetary sectors (though not necessarily in other sectors, such as labor markets): both product markets and money markets are in equilibrium. This equilibrium yields a unique combination of interest rates and real GDP.

Shifts

One Keynesian hypothesis is that a government's deficit spending has an effect similar to that of a lower saving rate or increased private fixed investment, increasing the amount of aggregate demand for national income at each individual interest rate. An increased deficit by the national government shifts the IS curve to the right. This raises the equilibrium interest rate (from i1 to i2) and national income (from Y1 to Y2), as shown in the graph above.

The graph indicates one of the major criticisms of deficit spending as a way to stimulate the economy: rising interest rates lead to crowding out – i.e., discouragement – of private fixed investment, which in turn may hurt long-term growth of the supply side (potential output). Keynesians respond that deficit spending may actually "crowd in" (encourage) private fixed investment via the accelerator effect, which helps long-term growth. Further, if government deficits are spent on productive public investment (e.g., infrastructure or public health) that directly and eventually raises potential output.

The IS/LM model also allows for the role of monetary policy. If the money supply is increased, that shifts the LM curve to the right, lowering interest rates and raising equilibrium national income.

In all this, the price level is assumed as fixed and no inflation is taken into consideration. To include them and other crucial issues, several further curves and diagrams are needed. To keep everything in one sheet, one has to shift from the representation through diagrams (in Cartesian spaces) to graphs (nodes and arrows), as defined by Graph theory. An interactive graph of all IS-LM variables and their linkages is provided at http://www.economicswebinstitute.org/essays/is-lm2.htm.

History

The IS/LM model was born at the Econometric Conference held in Oxford during September, 1936. Roy Harrod, John R. Hicks, and James Meade all presented papers describing mathematical models attempting to summarize John Maynard Keynes' General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Hicks, who had seen a draft of Harrod's paper, invented the IS/LM model. He later presented it in "Mr. Keynes and the Classics: A Suggested Interpretation" (Econometrica, April 1937).

Hicks later agreed that the model missed important points from the Keynesian theory. The problem was that it presents the real and monetary sectors as separate, something Keynes attempted to transcend. In addition, an equilibrium model ignores uncertainty. A shift in the IS or LM curve will cause change in expectations, causing the other curve to shift. Hicks therefore created a new Hicks-Hansen IS-LM Model to resolve some of the problems. Most modern macroeconomists see the IS/LM model as being at best a first approximation for understanding the real world.

Although the model is generally not taught at the graduate level, a few graduate programs (UNC Greensboro, Auburn University, Florida State,) continue to use it as part of the macroeconomics curriculum. It is also still the dominant paradigm in undergraduate macroeconomics textbooks, although many dynamicists would insist that it is past its prime even in an undergraduate context.

Related Models

External links

- Elmer G. Wiens: IS-LM Model - An On-line, Interactive IS-LM Model of the Canadian Economy.

- The Hicks-Hansel IS-LM Model: [2] in-depth comment and explanation.