Kepler's laws of planetary motion: Difference between revisions

m →There is an alternate derivation available for keplers first law.: citation needed |

|||

| Line 247: | Line 247: | ||

Then by conservation of angular momentum (as no external force acts on the system) : |

Then by conservation of angular momentum (as no external force acts on the system) : |

||

mvrsin(x)= constant |

'''mvrsin(x) = L = constant''' |

||

So, '''vrsin(x) is constant'''. |

|||

Also by conservation of energy : |

Also by conservation of energy : |

||

'''1/2(mv<sup>2</sup>) - GMm/r<sup>2</sup> = constant''' |

'''1/2(mv<sup>2</sup>) - GMm/r<sup>2</sup> = Total energy = TE = constant''' |

||

Plugging in the values from first equation, we get an equation of the form : |

Plugging in the values from first equation, we get an equation of the form : |

||

''' |

'''sin(x)= sqrt(1/(r<sup>2</sup>(2m(TE)/L<sup>2</sup>) + r(GMm<sup>2</sup>2/L<sup>2</sup>)''' |

||

| ⚫ | which is infact an equation of ellipse for the constant (2m(TE)/L<sup>2</sup>) less than zero. This will happen when the velocity of the body is between the minimum orbital velocity and escape velocity. At this interval : - GMm/2R <= TE < 0 and the equality will hold when the orbit is circular. At TE>=0 the graph of the equation turns out to be a hyperbola and the equality holds when the orbit is parabolic. |

||

'''Proof for equation of an ellipse in sin(x) form :''' |

|||

A lot of people dont use this form of an ellipse and stick with the conventional equation of an ellipse. But its very useful at times when dealing with conic sections. |

|||

Imagine an ellipse centred at the origin, having its focii at +ae,-ae (e is the eccentricity). a,b be respectively the major and minor axis of the ellipse. x be the angle made by a tangent at a point on the ellipse with the lines coming from the focii to that point. By definition, the two angles formed by lines from the two focii to that point with the tangent are equal. So considering the triangle formed by those two lines (having angle between themselves 180 - 2x by linear pair) , and the line formed by joining the focii (having magnitude 2ae), the cosine formula of triangle is applied : |

|||

cos(180-2x) = (l<sup>2</sup> + m<sup>2</sup> - n<sup>2</sup>) / 2lm |

|||

-cos(2x) = ((l+m)<sup>2</sup> - 2lm - n<sup>2</sup>)/2lm |

|||

-cos(2x) = ((2a)<sup>2</sup> - 2lm - (2ae)<sup>2</sup>)/2lm |

|||

1 - cos(2x) = (4(a)<sup>2</sup> - 4(ae)<sup>2</sup>)/2lm |

|||

2sin<sup>2</sup>(x) = 4(a<sup>2</sup>(1-e<sup>2</sup>)/2l(2a-1) |

|||

sin<sup>2</sup>(x) = a<sup>2</sup>(1-e<sup>2</sup>)/l(2a-l) |

|||

sin<sup>2</sup>(x) = b<sup>2</sup>/l(2a-l) |

|||

'''sin(x) = sqrt ( 1/ l(2a/b<sup>2</sup>) - l<sup>2</sup>/b<sup>2</sup>)''' |

|||

The above equation is an equation of ellipse. This is the equation we obtained in the derivation of keplers first law. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Condition for circular orbit : Velocity = minimum orbital velocity.''' |

'''Condition for circular orbit : Velocity = minimum orbital velocity.''' |

||

| Line 264: | Line 288: | ||

'''Condition for ellitical orbit : minimum orbital velocity < Velocity < escape velocity.''' |

'''Condition for ellitical orbit : minimum orbital velocity < Velocity < escape velocity.''' |

||

'''Condition for |

'''Condition for parabolic orbit : Velocity = escape velocity.''' |

||

'''Condition for hyperbolic orbit : Velocity > escape velocity.''' |

|||

where escape velocity is sqrt(2GM/r) and minimum orbital velocity is sqrt(GM/r). |

where escape velocity is sqrt(2GM/r) and minimum orbital velocity is sqrt(GM/r). |

||

Revision as of 18:53, 19 October 2008

In astronomy, Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion are three mathematical laws that describe the motion of planets in the Solar System. German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) discovered them.

Kepler studied the observations (the Rudolphine tables) of Tycho Brahe. Around 1605, Kepler found that Brahe's observations of the planets' positions followed three relatively simple mathematical laws.

Kepler's laws challenged Aristotelean and Ptolemaic astronomy and physics. His assertion that the Earth moved, his use of ellipses rather than epicycles, and his proof that the planets' speeds varied, changed astronomy and physics. Almost a century later Isaac Newton was able to deduce Kepler's laws from Newton's own laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation, using classical Euclidean geometry.

In modern times, Kepler's laws are used to calculate approximate orbits for artificial satellites, and bodies orbiting the Sun of which Kepler was unaware (such as the outer planets and smaller asteroids). They apply where any relatively small body is orbiting a larger, relatively massive body, though the effects of atmospheric drag (e.g. in a low orbit), relativity (e.g. Perihelion precession of Mercury), and other nearby bodies can make the results insufficiently accurate for a specific purpose.

Kepler's laws are formulated below using heliocentric polar coordinates. However, they can alternatively be formulated and derived using Cartesian coordinates.[1]

First law

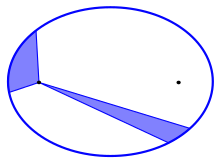

The first law says:"The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the sun at one of the foci."

The mathematics of the ellipse is as follows. The equation is

where (r,ν) are heliocentricical polar coordinates for the planet, p is the semi-latus rectum, and ε is the eccentricity, which is greater than or equal to zero, and less than one. For ν=0 the planet is at the perihelion at minimum distance:

for ν=90°: r=p, and for ν=180° the planet is at the aphelion at maximum distance:

The semi-major axis is the arithmetic mean between rmin and rmax:

The semi-minor axis is the geometric mean between rmin and rmax:

and it is also the geometric mean between the semimajor axis and the semi latus rectum:

Second law

The second law: "A line joining a planet and the sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time."[2]

This is also known as the law of equal areas. It is a direct consequence of the law of conservation of angular momentum; see the derivation below.

Suppose a planet takes one day to travel from point A to B. The lines from the Sun to A and B, together with the planet orbit, will define a (roughly triangular) area. This same amount of area will be formed every day regardless of where in its orbit the planet is. This means that the planet moves faster when it is closer to the sun.

This is because the sun's gravity accelerates the planet as it falls toward the sun, and decelerates it on the way back out, but Kepler did not know that reason.

The two laws permitted Kepler to calculate the position, (r,ν), of the planet, based on the time since perihelion, t, and the orbital period, P. The calculation is done in four steps.

- 1. Compute the mean anomaly M from the formula

- 2. Compute the eccentric anomaly E by numerically solving Kepler's equation:

- 3. Compute the true anomaly ν by the equation:

- 4. Compute the heliocentric distance r from the first law:

The proof of this procedure is shown below.

Third law

The third law : "The squares of the orbital periods of planets are directly proportional to the cubes of the axes of the orbits." Thus, not only does the length of the orbit increase with distance, the orbital speed decreases, so that the increase of the orbital period is more than proportional.

- = orbital period of planet

- = semimajor axis of orbit

So the expression P2·a–3 has the same value for all planets in the Solar System as it has for Earth. When certain units are chosen, namely P is measured in sidereal years and a in astronomical units, P2·a–3 has the value 1 for all planets in the Solar System.

In SI units: .

The law, when applied to circular orbits where the acceleration is proportional to a·P−2, shows that the acceleration is proportional to a·a−3 = a−2, in accordance with Newton's law of gravitation.

The general equation, which was derived from Newton's law of gravity, is

where is the gravitational constant, is the mass of the sun, and is the mass of planet. The latter appears in the equation since the equation of motion involves the reduced mass. Note that P is time per orbit and P/2π is time per radian.

See the actual figures: attributes of major planets.

This law is also known as the harmonic law.

Position as a function of time

The Keplerian problem assumes an elliptical orbit and the four points:

- s the sun (at one focus of ellipse);

- z the perihelion

- c the center of the ellipse

- p the planet

and

- distance from center to perihelion, the semimajor axis,

- the eccentricity,

- the semiminor axis,

- the distance from sun to planet.

and the angle

- the planet as seen from the sun, the true anomaly.

The problem is to compute the polar coordinates (r,ν) of the planet from the time since perihelion, t.

It is solved in steps. Kepler began by adding the orbit's auxiliary circle (that with the major axis as a diameter) and defined these points:

- x is the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle; then the area

- y is a point on the auxiliary circle such that the area

and

- , y as seen from the centre, the mean anomaly.

The area of the circular sector , and the area swept since perihelion,

- ,

is by Kepler's second law proportional to time since perihelion. So the mean anomaly, M, is proportional to time since perihelion, t.

where P is the orbital period.

The mean anomaly M is first computed. The goal is to compute the true anomaly ν. The function ν=f(M) is, however, not elementary. Kepler's solution is to use

- , x as seen from the centre, the eccentric anomaly

as an intermediate variable, and first compute E as a function of M by solving Kepler's equation below, and then compute the true anomaly ν from the eccentric anomaly E. Here are the details.

Division by a²/2 gives Kepler's equation

- .

The catch is that Kepler's equation cannot be rearranged to isolate E. The function E=f(M) is not an elementary formula, but Kepler's equation is solved either iteratively by a root-finding algorithm or, as derived in the article on eccentric anomaly, by an infinite series.

Having computed the eccentric anomaly E from Kepler's equation, the next step is to calculate the true anomaly ν from the eccentric anomaly E.

Note from the geometry of the problem that

Dividing by a and inserting from Kepler's first law

to get

The result is a usable relationship between the eccentric anomaly E and the true anomaly ν.

A computationally more convenient form follows by substituting into the trigonometric identity:

Get

Multiplying by (1+ε)/(1−ε) and taking the square root gives the result

We have now completed the third step in the connection between time and position in the orbit.

One could even develop a series computing ν directly from M. [1]

The fourth step is to compute the heliocentric distance r from the true anomaly ν by Kepler's first law:

Derivation from Newton's laws

Kepler's laws are about the motion of the planets around the sun, while Newton's laws more generally are about the motion of point particles attracting each other by the force of gravitation.

In the special case where there are only two particles, and one of them is much lighter than the other, and the distance between the particles remains limited, then the lighter particle moves around the heavy particle as a planet around the Sun according to Kepler's laws, as shown below.

Newton's laws however admit solutions, see the article on the two body problem, where the trajectory of the lighter particle may also be a parabola or a hyperbola or a straight line.

Newton's laws imply that the focus of the ellipse is at the centre of mass of the sun and the planet, rather than at the sun alone, - that the period of the orbit depends a little on the mass of the planet, - and that interaction from other planets modifies the orbit of a planet. Still the language of Kepler's laws applies as the complicated orbits are described as simple Kepler orbits with slowly varying orbital elements. See also Kepler problem in general relativity.

While Kepler's laws are expressed either in geometrical language, or as equations connecting the coordinates of the planet and the time variable with the orbital elements, Newton's second law is a differential equation. So the derivations below involve the art of solving differential equations. Kepler's second law is derived first, as the derivation of the first law depends on the derivation of the second law.

Deriving Kepler's second law

Newton's law of gravitation says that "every object in the universe attracts every other object along a line of the centers of the objects, proportional to each object's mass, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the objects," and his second law of motion says that "the mass times the acceleration is equal to the force." So the mass of the planet times the acceleration vector of the planet equals the mass of the sun times the mass of the planet, divided by the square of the distance, times minus the radial unit vector, times a constant of proportionality. This is written:

where a dot on top of the variable signifies differentiation with respect to time, and the second dot indicates the second derivative.

Assume that the planet is so much lighter than the sun that the acceleration of the sun can be neglected.

where is the tangential unit vector, and

So the position vector

is differentiated twice to give the velocity vector and the acceleration vector

Note that for constant distance, , the planet is subject to the centripetal acceleration, , and for constant angular speed, , the planet is subject to the coriolis acceleration, .

Inserting the acceleration vector into Newton's laws, and dividing by m, gives the vector equation of motion

Equating component, we get the two ordinary differential equations of motion, one for the radial acceleration and one for the tangential acceleration:

In order to derive Kepler's second law only the tangential acceleration equation is needed. Divide it by

and integrate:

where is a constant of integration, and exponentiate:

This says that the specific angular momentum is a constant of motion, even if both the distance and the angular speed vary.

The area swept out from time t1 to time t2,

depends only on the duration t2−t1. This is Kepler's second law.

Deriving Kepler's first law

The expression

has the dimension of length and is used to make the equations of motion dimensionless. We define

and get

and

Differentiation with respect to time is transformed into differentiation with respect to angle:

Differentiate

twice:

Substitute into the radial equation of motion

and get

Divide by to get a simple non-homogeneous linear differential equation for the orbit of the planet:

An obvious solution to this equation is the circular orbit

Other solutions are obtained by adding solutions to the homogeneous linear differential equation with constant coefficients

These solutions are

where and are arbitrary constants of integration. So the result is

Choosing the axis of the coordinate system such that , and inserting , gives:

If this is Kepler's first law.

There is an alternate derivation available for keplers first law.

The angle between velocity vector (v) and radius vector (r) be x. Then by conservation of angular momentum (as no external force acts on the system) :

mvrsin(x) = L = constant

Also by conservation of energy :

1/2(mv2) - GMm/r2 = Total energy = TE = constant

Plugging in the values from first equation, we get an equation of the form :

sin(x)= sqrt(1/(r2(2m(TE)/L2) + r(GMm22/L2)

which is infact an equation of ellipse for the constant (2m(TE)/L2) less than zero. This will happen when the velocity of the body is between the minimum orbital velocity and escape velocity. At this interval : - GMm/2R <= TE < 0 and the equality will hold when the orbit is circular. At TE>=0 the graph of the equation turns out to be a hyperbola and the equality holds when the orbit is parabolic.

Proof for equation of an ellipse in sin(x) form :

A lot of people dont use this form of an ellipse and stick with the conventional equation of an ellipse. But its very useful at times when dealing with conic sections.

Imagine an ellipse centred at the origin, having its focii at +ae,-ae (e is the eccentricity). a,b be respectively the major and minor axis of the ellipse. x be the angle made by a tangent at a point on the ellipse with the lines coming from the focii to that point. By definition, the two angles formed by lines from the two focii to that point with the tangent are equal. So considering the triangle formed by those two lines (having angle between themselves 180 - 2x by linear pair) , and the line formed by joining the focii (having magnitude 2ae), the cosine formula of triangle is applied :

cos(180-2x) = (l2 + m2 - n2) / 2lm

-cos(2x) = ((l+m)2 - 2lm - n2)/2lm

-cos(2x) = ((2a)2 - 2lm - (2ae)2)/2lm

1 - cos(2x) = (4(a)2 - 4(ae)2)/2lm

2sin2(x) = 4(a2(1-e2)/2l(2a-1)

sin2(x) = a2(1-e2)/l(2a-l)

sin2(x) = b2/l(2a-l)

sin(x) = sqrt ( 1/ l(2a/b2) - l2/b2)

The above equation is an equation of ellipse. This is the equation we obtained in the derivation of keplers first law.

Condition for circular orbit : Velocity = minimum orbital velocity.

Condition for ellitical orbit : minimum orbital velocity < Velocity < escape velocity.

Condition for parabolic orbit : Velocity = escape velocity.

Condition for hyperbolic orbit : Velocity > escape velocity.

where escape velocity is sqrt(2GM/r) and minimum orbital velocity is sqrt(GM/r).

Deriving Kepler's third law

The area of the planetary orbit ellipse is

The area speed of the radius vector sweeping the orbit area is

where

The period of the orbit is

satisfying

which is Kepler's third law.

Keplers third law can also be derived easily assuming circular motion.

GMm/r2=mv2

v=sqrt(GM/r)

T=2(pi)r/v

2(pi)r3/2/sqrt(GM)

therefore,

T2=4(pi)2r3/GM

so

T2 proportional to r3.

Hence the proof.

Notes

- ^ Hyman, Andrew. "A Simple Cartesian Treatment of Planetary Motion", European Journal of Physics, Vol. 14, pp. 145-147 (1993).

- ^ "Kepler's Second Law" by Jeff Bryant with Oleksandr Pavlyk, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

References

- Kepler's life is summarized on pages 627-623 and Book Five of his magnum opus, Harmonice Mundi (harmonies of the world), is reprinted on pages 635-732 of On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (works by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein). Stephen Hawking, ed. 2002 ISBN 0-7624-1348-4

- A derivation of Kepler's third law of planetary motion is a standard topic in engineering mechanics classes. See, for example, pages 161-164 of Meriam, J. L. (1966, 1971), Dynamics, 2nd ed., New York: John Wiley, ISBN 0-471-59601-9

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link).

- Murray and Dermott, Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press 1999, ISBN-10 0-521-57597-4

See also

- Kepler orbit

- Kepler problem

- Circular motion

- Gravity

- Two-body problem

- Free-fall time

- Laplace-Runge-Lenz vector

External links

- B.Surendranath Reddy; animation of Kepler's laws: applet

- Crowell, Benjamin, Conservation Laws, http://www.lightandmatter.com/area1book2.html, an online book that gives a proof of the first law without the use of calculus. (see section 5.2, p.112)

- David McNamara and Gianfranco Vidali, Kepler's Second Law - Java Interactive Tutorial, http://www.phy.syr.edu/courses/java/mc_html/kepler.html, an interactive Java applet that aids in the understanding of Kepler's Second Law.

- University of Tennessee's Dept. Physics & Astronomy: Astronomy 161 page on Johannes Kepler: The Laws of Planetary Motion [2]

- Equant compared to Kepler: interactive model [3]

- Kepler's Third Law:interactive model[4]