Golf ball: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 32.149.217.193 to last version by User name one |

→Design: Direct link to Callaway Golf company rather than disambiguation page |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

Officially sanctioned balls are designed to be as [[symmetry|symmetrical]] as possible. This symmetry is the result of a dispute that stemmed from the Polara, a ball sold in the late 1970s that had six rows of normal dimples on its equator but very shallow dimples elsewhere. This asymmetrical design helped the ball self-adjust its [[spin (physics)|spin]]-axis during the flight. The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls. Polara's producer sued the USGA and the association paid US$1.375 million in a 1985 out-of-court settlement. |

Officially sanctioned balls are designed to be as [[symmetry|symmetrical]] as possible. This symmetry is the result of a dispute that stemmed from the Polara, a ball sold in the late 1970s that had six rows of normal dimples on its equator but very shallow dimples elsewhere. This asymmetrical design helped the ball self-adjust its [[spin (physics)|spin]]-axis during the flight. The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls. Polara's producer sued the USGA and the association paid US$1.375 million in a 1985 out-of-court settlement. |

||

Golf equipment maker [[Callaway]] has introduced a ball with hexagonal dimples to increase the dimpled area on a golf ball, as hexagons tesselate unlike circles. |

Golf equipment maker [[Callaway_Golf|Callaway]] has introduced a ball with hexagonal dimples to increase the dimpled area on a golf ball, as hexagons tesselate unlike circles. |

||

The [[United States Patent and Trademark Office]]'s [[patent]] [[database]] is a good source of past dimple designs. Most designs are based on [[Platonic solid]]s such as [[icosahedron]]. |

The [[United States Patent and Trademark Office]]'s [[patent]] [[database]] is a good source of past dimple designs. Most designs are based on [[Platonic solid]]s such as [[icosahedron]]. |

||

Revision as of 15:28, 24 December 2008

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2008) |

A golf ball is a ball designed to be used in the game of golf.

A regulation golf ball weighs no more than 1.620 oz (45.93 grams), with a diameter over 1.680 in (42.67 mm), and is symmetrically spherical in shape. Like golf clubs, golf balls are subject to testing and approval by the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews and the United States Golf Association, and those that do not conform with regulations may not be used in competitions (Rule 5-1 — also see rules of golf)

History

Wooden balls were used until the early 17th century, when the featherie ball was invented. This added a new and exciting feature to the game of golf. A featherie is a hand sewn leather pouch stuffed with goose feathers and coated with paint. The feathers in the ball were enough to fill a top hat. They were boiled and put in the cowhide bag. As it cooled, the feathers would expand and the hide would shrink, making a compact ball. Due to its superior flight characteristics, the featherie remained the standard ball for more than two centuries. However, an experienced ball maker could only make a few balls in one day, so they were expensive. A single ball would cost between 2 shillings and sixpence and 5 shillings, which is the equivalent of around 10 to 20 US dollars today [1]. Also, it was hard to make a perfectly spherical ball, and because of that, the ball often flew irregularly. When playing in wet weather, the stiches in the ball would rot, and the ball would split open after hitting a hard surface.

In 1848, the Rev. Dr. Robert Adams (or Robert Adam Paterson)[2] invented the gutta-percha ball (or guttie). The gutta was created from dried sap of a Sapodilla Tree. The sap had a rubber-like feel and could be made round by heating and shaping it while hot. Accidentally, it was discovered that defects in the sphere could provide a ball with a truer flight than a pure sphere. Thus, makers started creating intentional defects in the surface to have a more consistent ball flight. Because gutties were cheaper to produce and could be manufactured with textured surfaces to improve their aerodynamic qualities, they replaced feather balls completely within a few years.

In the 20th century, multi-layer balls were developed, first as wound balls consisting of a solid or liquid-filled core wound with a layer of rubber thread and a thin outer shell. This idea was first discovered by Coburn Haskell of Cleveland, Ohio in 1898. Haskell had driven to nearby Akron to keep a golf date with Bertram Work, then superintendent of B.F. Goodrich. While he waited for Work at the plant, Haskell idly wound a long rubber thread into a ball. When he bounced the ball, it flew almost to the ceiling. Work suggested Haskell put a cover on the creation, and that was the birth of the 20th century golf ball. The design allowed manufacturers to fine-tune the length, spin and "feel" characteristics of balls. Wound balls were especially valued for their soft feel.

They usually consist of a two-, three-, or four-layer design, (named either a two-piece, three-piece, or four-piece ball) consisting of various synthetic materials like surlyn or urethane blends. They come in a great variety of playing characteristics to suit the needs of golfers of different abilities.

Regulations

The current regulations mandated by the R&A and the USGA state that diameter of the golf ball cannot be any smaller than 1.680 inches. The maximum velocity of the ball may not exceed 250 feet per second under test conditions and the weight of the ball may not exceed 1.620 ounces.

Until 1990 it was permissible to use balls of no less than 1.62 inches in diameter in tournaments under the jurisdiction of the R&A[3].

Aerodynamics

When a golf ball is hit, the impact, which lasts less than a millisecond, determines the ball’s velocity, launch angle and spin rate, all of which influence its trajectory (and its behavior when it hits the ground).

A ball moving through air experiences two major aerodynamic forces, lift and drag. Dimpled balls fly farther than non-dimpled balls due to the combination of two effects:

Firstly, the dimples delay separation of the boundary layer from the ball. Early separation, as seen on a smooth sphere, causes significant wake turbulence, the principal cause of drag. The separation delay caused by the dimples therefore reduces this wake turbulence, and hence the drag.

Secondly, backspin generates lift by deforming the airflow around the ball, in a similar manner to an airplane wing. This is called the Magnus effect. Backspin is imparted in almost every shot due to the golf club's loft (i.e. angle between the clubface and a vertical plane). A backspinning ball experiences an upward lift force which makes it fly higher and longer than a ball without spin.[1] Sidespin occurs when the clubface is not aligned perpendicularly to the direction of swing, leading to a lift force that makes the ball curve to one side or the other. Unfortunately the dimples magnify this effect as well as the more desirable upward lift derived from pure backspin. (Some dimple designs are claimed to reduce sidespin effects.)

In order to keep the aerodynamics optimal, the ball needs to be clean. Golfers can wash their balls manually, but there are also mechanical ball washers available.

Design

Dimples first became a feature of golf balls when a certain Taylor patented a dimple design in 1908. Other types of patterned covers were in use at about the same time, including one called a "mesh" and another named the "bramble", but the dimple became the dominant design due to "the superiority of the dimpled cover in flight".[4]

Most golf balls on sale today have about 250 – 450 dimples. There were a few balls having over 500 dimples before. The record holder was a ball with 1,070 dimples — 414 larger ones (in four different sizes) and 656 pinhead-sized ones. All brands of balls, except one, have even-numbered dimples. The only odd-numbered ball on the market is a ball with 333 dimples, called the Srixon AD333.

Officially sanctioned balls are designed to be as symmetrical as possible. This symmetry is the result of a dispute that stemmed from the Polara, a ball sold in the late 1970s that had six rows of normal dimples on its equator but very shallow dimples elsewhere. This asymmetrical design helped the ball self-adjust its spin-axis during the flight. The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls. Polara's producer sued the USGA and the association paid US$1.375 million in a 1985 out-of-court settlement.

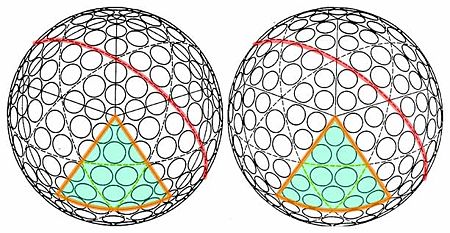

Golf equipment maker Callaway has introduced a ball with hexagonal dimples to increase the dimpled area on a golf ball, as hexagons tesselate unlike circles.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office's patent database is a good source of past dimple designs. Most designs are based on Platonic solids such as icosahedron.

Golf balls are usually white, but are available in other high visibility colours , which helps with finding the ball when lost or when playing in frosty conditions. As well as bearing the makers name or logo, balls are usually printed with numbers or other symbols to help players identify their ball.

Selection

There are many types of golf balls on the market, and customers often face a difficult decision. Golf balls are divided into two categories: recreational and advanced balls. Recreational balls are oriented toward the ordinary golfer, who generally have low swing speeds (80 miles per hour or lower) and lose golf balls on the course easily. These balls are made of two layers, with the cover firmer than the core. Their low compression and side spin reduction characteristics suit the lower swing speeds of average golfers quite well. Furthermore, they generally have lower prices than the advanced balls.

Advanced balls are made of multiple layers (three or more), with a soft cover and firm core. They induce a greater amount of spin from lofted shots (wedges especially), as well as a sensation of softness in the hands in short-range shots. However, these balls require a much greater swing speed that only the physically strong players could carry out to compress at impact. If the compression of a golf ball does not match a golfer's swing speed, either the lack of compression or over-compression will occur, resulting in loss of distance. There are also many brands and colors to choose from, with colored balls and better brands generally being more expensive, making an individual's choice more difficult.

Trick Balls

A number of designs of novelty ball have been introduced over the years, mainly as practical jokes for the amusement of fellow golfers, but also as "cheater" balls that do not conform to the Rules of Golf. All of these are banned in sanctioned games, but can be amusing in informal play:

- Breakaway balls are brittle and hollow, and shatter into many small pieces when hit.

- Exploding balls are similar, but employ a small explosive device that disintegrates the ball when hit. Many courses have banned these as the charge can damage the turf, the player's club or even cause injury, leading manufacturers to develop the breakaway.

- Stallers are far softer than a normal golf ball, allowing them to be compressed far more easily and are given greater backspin when hit. Both of these give the ball a huge amount of lift, making shots climb very high into the air with very little distance travelled over the ground. In the right conditions, such a ball may travel backwards along its flight path or even perform a loop-the-loop.

- Sponge balls are softer still; they are generally used as indoor or backyard practice balls, but some are deceptively similar in appearance to a normal ball. Such a ball will travel less than a quarter of the distance of a normal golf ball.

- Wobblers have a center of mass that is not in the exact center of the ball or is loose within the ball. When putted, the ball will move unpredictably off the intended line.

- Floaters are less dense than a regulation golf ball so when hit into a water hazard, they bob on the surface when a normal ball would sink.

- Super-distance balls have deeper dimples and are heavier than allowed by regulation, which allows them first to maintain momentum and second to maintain a thicker "envelope" of still air around them which reduces turbulence and wind resistance. Marketers of these balls generally advertise a 12-yard gain on most distance shots.

Used and refurbished golf balls

Used golf balls are golf balls that have been played, most likely hit into a water hazard, then retrieved, cleaned up and resold. Used golf balls comes in different gradings - one well-accepted standard is:[2]

| AAAAA (1st Quality) | AAAA (2nd Quality) | AAA (3rd Quality) | AA (4th Quality) |

| Highest quality ball in the marketplace. Like new, perfect to very near perfect. A "One Hit Wonder" Ball. | Very slightly blemished balls. May have minor imperfections. | Slightly scuffed or blemished balls that may have minor discoloration. | Appropriate for range and green practice. Survived a round of golf. |

Refinished, sometimes called reconditioned or refurbished, golf balls are different than used. Refinished golf balls may look new, but do not meet the manufacturer's original requirements. In the processing procedure, the golf ball is stripped of its original surface paint and reprinted with the original markings, then a new clear/coat is applied.

Radio Location

Golf balls with embedded radio transmitters to allow lost balls to be located were first introduced in 1973, only to be rapidly banned for use in competition[5][6]. More recently RFID transponders have been used for this purpose. This technology can be found in some computerized driving ranges. In this format, each ball used at the range has its own unique transponder code. When dispensed, the range registers each dispensed ball to the player, who then hits them towards targets in the range. When the player hits a ball into a target, they receive distance and accuracy information calculated by the computer.

World records

Jason Zuback broke the world ball speed record on an episode of Sports Science with a golf ball speed of 328 km/h (204 mph)[citation needed]. The previous record of 302 km/h (188 mph) was held by José Ramón Areitio, a Jai Alai player[citation needed].

External links

- Distance Golf Ball Guide

- Selecting the best ball that fits you

- Golf Ball Dimples - How Many? (an article for children)

- Online golf ball museum with more than 1000 different golf balls

- Golf ball aerodynamics

- Player performance factors and playing conditions to consider in selecting an appropriate golf ball

- Flight Dynamics of Golf Balls

- Choose the proper golf ball for your game

History

- The evolution of the golf ball

- A history of the golf ball

- Evolution of the Dimpled Golf Ball

- Grading of a Recycled Golf Ball

- All about Golf Balls

- History of the golf ball at The Golf Course

- Why do golf balls have dimples?

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.golfclubatlas.com/interviewcook.html Kevin Cook, former editor-in-chief of Golf Magazine interviewed by Golf Club Atlas

- ^ Sources conflict as to the exact name.

- ^ http://golf.about.com/cs/historyofgolf/p/timeline1990.htm

- ^ Feldman, David (1989). When Do Fish Sleep? And Other Imponderables of Everyday Life. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. p. 46. ISBN 0-06-016161-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.ruleshistory.com/clubs.html History of the rules of golf

- ^ http://www.freepatentsonline.com/3782730.html US Patent 3782730