Continuous function (topology): Difference between revisions

→Neighborhood definition: Providing further clarity e.g. see page 4 of http://www.dpmms.cam.ac.uk/site2002/Teaching/IB/MetricTopologicalSpaces/2005-2006/L1topspaces.pdf |

|||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

=== Neighborhood definition === |

=== Neighborhood definition === |

||

Definitions based on preimages are often difficult to use directly. Instead, suppose we have a function ''f'' |

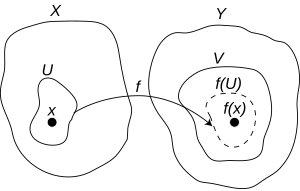

Definitions based on preimages are often difficult to use directly. Instead, suppose we have a function ''f'' : ''X'' → ''Y'' between two [[topological space]]s {''X'',''T<sub>X</sub>''} and {''Y'',''T<sub>Y</sub>''}. We say ''f'' is '''continuous at ''x''''' for some <math>x \in X</math> if for any [[neighborhood (topology)|neighborhood]] ''V'' of ''f''(''x''), there is a neighborhood ''U'' of ''x'' such that <math>f(U) \subseteq V</math>. |

||

Although this definition appears complicated, the intuition is that no matter how "small" ''V'' becomes, we can always find a ''U'' containing ''x'' that will map inside it. If ''f'' is continuous at every <math>x \in X</math>, then we simply say ''f'' is continuous. |

Although this definition appears complicated, the intuition is that no matter how "small" ''V'' becomes, we can always find a ''U'' containing ''x'' that will map inside it. If ''f'' is continuous at every <math>x \in X</math>, then we simply say ''f'' is continuous. |

||

Revision as of 19:55, 31 January 2009

In topology and related areas of mathematics a continuous function is a morphism between topological spaces. Intuitively, this is a function f where a set of points near f(x) always contain the image of a set of points near x. For a general topological space, this means a neighbourhood of f(x) always contains the image of a neighbourhood of x.

In a metric space (for example, the real numbers) this means that the points within a given distance of f(x) always contain the images of all the points within some other distance of x, giving the ε-δ definition.

Definitions

Several equivalent definitions for a topological structure exist and thus there are several equivalent ways to define a continuous function.

Open and closed set definition

The most common notion of continuity in topology defines continuous functions as those functions for which the preimages of open sets are open. Similar to the open set formulation is the closed set formulation, which says that preimages of closed sets are closed.

Neighborhood definition

Definitions based on preimages are often difficult to use directly. Instead, suppose we have a function f : X → Y between two topological spaces {X,TX} and {Y,TY}. We say f is continuous at x for some if for any neighborhood V of f(x), there is a neighborhood U of x such that . Although this definition appears complicated, the intuition is that no matter how "small" V becomes, we can always find a U containing x that will map inside it. If f is continuous at every , then we simply say f is continuous.

In a metric space, it is equivalent to consider the neighbourhood system of open balls centered at x and f(x) instead of all neighborhoods. This leads to the standard δ-ε definition of a continuous function from real analysis, which says roughly that a function is continuous if all points close to x map to points close to f(x). This only really makes sense in a metric space, however, which has a notion of distance.

Note, however, that if the target space is Hausdorff, it is still true that f is continuous at a if and only if the limit of f as x approaches a is f(a). At an isolated point, every function is continuous.

Sequences and nets

In several contexts, the topology of a space is conveniently specified in terms of limit points. In many instances, this is accomplished by specifying when a point is the limit of a sequence, but for some spaces that are too large in some sense, one specifies also when a point is the limit of more general sets of points indexed by a directed set, known as nets. A function is continuous only if it takes limits of sequences to limits of sequences. In the former case, preservation of limits is also sufficient; in the latter, a function may preserve all limits of sequences yet still fail to be continuous, and preservation of nets is a necessary and sufficient condition.

In detail, a function f : X → Y is sequentially continuous if whenever a sequence (xn) in X converges to a limit x, the sequence (f(xn)) converges to f(x). Thus sequentially continuous functions "preserve sequential limits". Every continuous function is sequentially continuous. If X is a first-countable space, then the converse also holds: any function preserving sequential limits is continuous. In particular, if X is a metric space, sequential continuity and continuity are equivalent. For non first-countable spaces, sequential continuity might be strictly weaker than continuity. (The spaces for which the two properties are equivalent are called sequential spaces.) This motivates the consideration of nets instead of sequences in general topological spaces. Continuous functions preserve limits of nets, and in fact this property characterizes continuous functions.

Closure operator definition

Given two topological spaces (X,cl) and (X ' ,cl ') where cl and cl ' are two closure operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X

One might therefore suspect that given two topological spaces (X,int) and (X ' ,int ') where int and int ' are two interior operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X

or perhaps if

however, neither of these conditions is either necessary or sufficient for continuity.

Instead, we must resort to inverse images: given two topological spaces (X,int) and (X ' ,int ') where int and int ' are two interior operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X '

We can also write that given two topological spaces (X,cl) and (X ' ,cl ') where cl and cl ' are two closure operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X '

Closeness relation definition

Given two topological spaces (X,δ) and (X' ,δ') where δ and δ' are two closeness relations then a function

is continuous if for all points x and of X and all subsets A of X,

This is another way of writing the closure operator definition.

Useful properties of continuous maps

Some facts about continuous maps between topological spaces:

- If f : X → Y and g : Y → Z are continuous, then so is the composition g o f : X → Z.

- If f : X → Y is continuous and

- X is compact, then f(X) is compact.

- X is connected, then f(X) is connected.

- X is path-connected, then f(X) is path-connected.

- The identity map idX : (X, τ2) → (X, τ1) is continuous if and only if τ1 ⊆ τ2 (see also comparison of topologies).

Other notes

If a set is given the discrete topology, all functions with that space as a domain are continuous. If the domain set is given the indiscrete topology and the range set is at least T0, then the only continuous functions are the constant functions. Conversely, any function whose range is indiscrete is continuous.

Given a set X, a partial ordering can be defined on the possible topologies on X. A continuous function between two topological spaces stays continuous if we strengthen the topology of the domain space or weaken the topology of the codomain space. Thus we can consider the continuity of a given function a topological property, depending only on the topologies of its domain and codomain spaces.

For a function f from a topological space X to a set S, one defines the final topology on S by letting the open sets of S be those subsets A of S for which f-1(A) is open in X. If S has an existing topology, f is continuous with respect to this topology if and only if the existing topology is coarser than the final topology on S. Thus the final topology can be characterized as the finest topology on S which makes f continuous. If f is surjective, this topology is canonically identified with the quotient topology under the equivalence relation defined by f. This construction can be generalized to an arbitrary family of functions X → S.

Dually, for a function f from a set S to a topological space, one defines the initial topology on S by letting the open sets of S be those subsets A of S for which f(A) is open in X. If S has an existing topology, f is continuous with respect to this topology if and only if the existing topology is finer than the initial topology on S. Thus the initial topology can be characterized as the coarsest topology on S which makes f continuous. If f is injective, this topology is canonically identified with the subspace topology of S, viewed as a subset of X. This construction can be generalized to an arbitrary family of functions S → X.

Symmetric to the concept of a continuous map is an open map, for which images of open sets are open. In fact, if an open map f has an inverse, that inverse is continuous, and if a continuous map g has an inverse, that inverse is open.

If a function is a bijection, then it has an inverse function. The inverse of a continuous bijection is open, but need not be continuous. If it is, this special function is called a homeomorphism. If a continuous bijection has as its domain a compact space and its codomain is Hausdorff, then it is automatically a homeomorphism.