Hydrazine sulfate: Difference between revisions

Physchim62 (talk | contribs) →Drug incompatibilities: combine with side-effects section |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

* [http://scri.ngen.com The Syracuse Cancer Research Institute] |

* [http://scri.ngen.com The Syracuse Cancer Research Institute] |

||

* [http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/PPI/UnconventionalTherapies/HydrazineSulfateHydrazineSulphate.htm Hydrazine sulfate / Hydrazine sulphate] from the British Columbia Cancer Agency |

* [http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/PPI/UnconventionalTherapies/HydrazineSulfateHydrazineSulphate.htm Hydrazine sulfate / Hydrazine sulphate] from the British Columbia Cancer Agency |

||

* [http://www.medtruth.blogspot.com Medtruth(blog)] |

|||

* [http://www.hydrazinesulfage.org THE TRUTH ABOUT HYDRAZINE SULFATE - DR. GOLD SPEAKS] |

* [http://www.hydrazinesulfage.org THE TRUTH ABOUT HYDRAZINE SULFATE - DR. GOLD SPEAKS] |

||

[[Category:Nitrogen compounds]] |

[[Category:Nitrogen compounds]] |

||

Revision as of 00:45, 31 May 2009

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Hydrazinium sulfate

| |

| Other names

Hydrazine sulphate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.088 |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

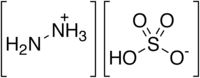

| H6N2O4S | |

| Molar mass | 130.12 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Hydrazine sulfate is the salt of hydrazine and sulfuric acid. Known by the trade name Sehydrin, it is a chemical compound that has been used as an alternative medical treatment for the loss of appetite (anorexia) and weight loss (cachexia) which is often associated with cancer.[1][2][3][4][5] It is thought to act as a gluconeogenic blocking agent irreversibly inhibiting the enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEP CK). It has never been approved as a mainstream drug, although it is approved for use in clinical trials by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is marketed in the United States as a dietary supplement.[6]

The use of hydrazine sulfate as a cancer remedy was popularized by the magazine Penthouse in the mid 1990s, when Kathy Keeton, wife and business partner of the magazine's publisher Bob Guccione, used it to treat her metastatic breast cancer.[7] Keeton and other supporters of hydrazine sulfate treatment accused the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) of deliberately hiding the beneficial effects of the compound, and threatened to launch a class action law suit.[8][9] The NCI denies the claims,[10] and says that there is little to no evidence that hydrazine sulfate has any beneficial effects whatsoever.[6] The position of the NCI was supported by an enquiry held by the General Accounting Office.[11]

A review of the clinical research concluded that hydrazine sulfate has never been shown to act as an anticancer agent; patients do not experience remissions or regressions of their cancer; and patients do not live longer than non-treated patients.[6][12]

Preparation

Hydrazine sulfate is cheaply available. It may be prepared by oxidizing aqueous ammonia with sodium hypochlorite to hydrazine, then precipitating with sulfuric acid.[13]

Background

Hydrazine sulfate was specifically developed as a result of a theoretical paper by Joseph Gold, M.D., indicating cancer glycolysis and normal-body gluconeogenesis to constitute a systemic (whole-body) energy-losing cycle as the biochemical and thermodynamic cause of cancer cachexia and postulating the inhibition of gluconeogenesis at the enzymic site of PEP CK to be an effective treatment for cancer cachexia.[14] It was also postulated that if tumor energy gain (glycolysis) and host-energy loss (gluconeogenesis) were functionally interrelated, inhibition of gluconeogenesis at PEP CK could result in actual tumor regression in addition to reversal or arrest of cancer cachexia.[15]

Investigational

Controlled clinical trials, performed in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration, indicated efficacy and safety in about 50 percent of all patients. Efficacy and safety were expressed in terms of appetite and weight improvements, performance status increase, decrease or disappearance of pain and weakness, tumor stabilization and regression and increased survival time. These multicentric Phase II and randomized, double-blind Phase III clinical trials were carried out at the Petrov Research Institute of Oncology in St. Petersburg (with the participation of the Herzen Institute of Oncology, Moscow, Oncological Institute of Lithuania, Vilnius, Institute of Oncology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Kiev, and Rostov Institute of Oncology and Radiology, Rostov an Donau) over a period of 17 years—and at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in California over period of 10 years, respectively. Studies were published chiefly in U.S. peer-reviewed, well known journals.

Side effects

Hydrazine sulfate is toxic and carcinogenic.[16][17] Nevertheless, the side-effects reported in the various clinical trials are remarkably mild:[18] minor nausea and vomiting, dizziness and excitement. More serious, even fatal side-effects have been reported in rare cases: one patient who devloped fatal liver and kidney failure,[19] another with serious symptoms of neurotoxicity.[20] These serious side effects are consistent with other reports of hydrazine toxicity,[16][17] and with toxic reactions to the antibiotic isoniazid, which is though to be metabolized to hydrazine in the body.[18]

Hydrazine sulfate is an MAO (monoamine oxidase) inhibitor and is incompatible with alcohol, tranquilizers, sleeping pills and other psycho-active drugs, with meperidine (Demerol), and with foods containing significant amounts of the amino acid tyramine, such as most cheeses, raisins, avocados, processed and cured fish and meats, fermented products, and others.

Costs

Hydrazine sulfate is a mass-produced chemical, used in myriad industrial applications and consequently very inexpensive. Drug grade hydrazine sulfate is reportedly dispensed by compounding pharmacies in 30 mg and 60 mg capsules or tablets at a cost ranging from $20.00 to $60.00 per 100 capsules or tablets, representing a one-to-two month supply.

References

- ^ Chlebowski, R. T.; Bulcavage, L.; Grosvenor, M.; et al. (1987), "Hydrazine Sulfate in Cancer Patients With Weight Loss. A Placebo-Controlled Clinical Experience", Cancer (59): 406–10

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Brauer, M.; Inculet, R. I.; Bratnager, G.; et al. (1994), "Insulin Protects against Hepatic Bioenergetic Deterioration by Cancer Cachexia. An in-Vivo 31P Magnetic Resonance Study.", Cancer Research (54): 6383–86

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Filov, V. A.; Gershanovich, M. L.; Danova, L. A.; Ivin, B. A. (1995), "Experience of the Treatment with Sehydrin (Hydrazine Sulfate, HS) in the Advanced Cancer Patients", Investigational New Drugs (13): 89–97

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Chlebowski, R. T.; Bulcavage, L.; Grosvenor, M.; et al. (1990), "Hydrazine Sulfate Influence on Nutritional Status and Survival in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer", Journal of Clinical Oncology (8): 9–15

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Gold, J. (1999), "Long term complete response in patient with advanced, localized NSCLC with hydrazine sulfate, radiation and Carboplatin, refractory to combination chemotherapy", Proceedings of the American Association for Cancer Research (40): 642.

- ^ a b c Questions and answers about hydrazine sulfate, National Cancer Institute, March 12, 2009

- ^ London, William M. (July 23, 2006), Penthouse's promotion of hydrazine sulfate

- ^ Goldberg, Burton (June 12, 2000), Holding the National Cancer Institute Accountable for Cancer Deaths

- ^ Goldberg, Burton; Trivieri, Larry; Anderson, John W., ed. (2002), Alternative medicine: the definitive guide (2nd ed.), Celestial Arts, pp. 50–51, 598, ISBN 1587611414

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link). - ^ Jenks, S. (1993), "Hydrazine Sulfate Ad Is "Offensive"", Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85 (7): 528–29, doi:10.1093/jnci/85.7.528

- ^ Nadel, M. V. (September 1995), "Cancer Drug Research—Contrary to Allegations, Hydrazine Sulfate Studies Were Not Flawed", Report to the Chairman and Ranking Minority Member, Human Resources and Intergovernmental Relations Subcommittee, House Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, Washington, D.C.: General Accounting Office, Document No. HEHS-95-141.

- ^ Green, Saul (1997), "Hydrazine sulfate: is it an anticancer agent?", Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, 1: 19–21

- ^ Roger Adams and B. K. Brown (1941). "Hydrazine sulfate". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 309.

- ^ Gold, J. (1968), "Proposed Treatment of Cancer by Inhibition of Gluconeogenesis", Oncology (22): 185–207.

- ^ Gold, J. (1974), "Cancer Cachexia and Gluconeogenesis", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (230): 103–10.

- ^ a b Hydrazine Hazard Summary, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, January 2000.

- ^ a b Section 9.2.1, Environmental Health Criteria for Hydrazine, International Programme on Chemical Safety, 1987.

- ^ a b Black, M.; Hussain, H. (2000), "Hydrazine, Cancer, the Internet, Isoniazid, and the Liver" (PDF), Annals of Internal Medicine, 133 (11): 911–13

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Hainer, M. I.; et al. (2000), "Fatal hepatorenal failure associated with hydrazine sulfate" (PDF), Annals of Internal Medicine, 133: 877–80

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help). - ^ Nagappan, R.; Riddell, T. (2000), "Pyridoxine therapy in a patient with severe hydrazine sulfate toxicity", Critical Care in Medicine, 28: 2116–18, PMID 10890675

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link).

External links

- The Syracuse Cancer Research Institute

- Hydrazine sulfate / Hydrazine sulphate from the British Columbia Cancer Agency

- THE TRUTH ABOUT HYDRAZINE SULFATE - DR. GOLD SPEAKS