Duluth lynchings: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 271450283 by 68.112.174.227 (talk) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

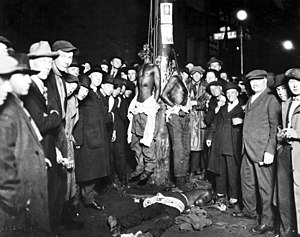

[[Image:Lynchedmen.JPG|thumb|300px|right|The Duluth memorial has been described by its artist as attempting to "reinvest [the victims] with their unique personalities", to counteract the way the lynchings "depersonalized" them.<ref name=doc>[http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-606428727324540926&q=the+duluth+lynchings Duluth Lynchings: Presence of the Past]. ''Twin Cities Public Television''.</ref>]] |

[[Image:Lynchedmen.JPG|thumb|300px|right|The Duluth memorial has been described by its artist as attempting to "reinvest [the victims] with their unique personalities", to counteract the way the lynchings "depersonalized" them.<ref name=doc>[http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-606428727324540926&q=the+duluth+lynchings Duluth Lynchings: Presence of the Past]. ''Twin Cities Public Television''.</ref>]] |

||

The '''Duluth Lynchings''' occurred on [[June 15]], [[1920]], when three black circus workers were attacked and [[Lynching|lynched]] by a mob in [[Duluth, Minnesota|Duluth]], [[Minnesota]]. Rumors had circulated among the mob that six |

The '''Duluth Lynchings''' occurred on [[June 15]], [[1920]], when three black circus workers were attacked and [[Lynching|lynched]] by a mob in [[Duluth, Minnesota|Duluth]], [[Minnesota]]. Rumors had circulated among the mob that six blacks had raped a teenage girl. A physician's examination subsequently found no evidence of rape or assault.<ref name=doc /><ref name="mnhs">{{cite web|last= |first= |authorlink= |coauthors= |date= |url=http://collections.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/ |title=Duluth Lynchings On line Resource |format= |work= |pages= |publisher=Minnesota Historical Society |accessdate=2006-03-09 |accessyear= }}</ref> |

||

The killings shocked the country, particularly for their having occurred in the northern United States.<ref>[http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0A16F63F5E1B728DDDAE0994DE405B808EF1D3 MOVE TO PUNISH DULUTH LYNCHERS]. ''New York Times''. June 17, 1920.</ref> In 2003, the city of Duluth erected a memorial to the murdered workers. |

The killings shocked the country, particularly for their having occurred in the northern United States.<ref>[http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FB0A16F63F5E1B728DDDAE0994DE405B808EF1D3 MOVE TO PUNISH DULUTH LYNCHERS]. ''New York Times''. June 17, 1920.</ref> In 2003, the city of Duluth erected a memorial to the murdered workers. |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

During and immediately following [[World War I]], a large population of [[African Americans]] emigrated from the [[South]] to the [[North]] and [[Midwest]] in search of job opportunities. The predominantly white-populated Midwest perceived the black migrant laborers as a threat to their employment, as well as to their ability to negotiate pay rates. [[US Steel]], for instance, the most important regional employer, addressed labor concerns by leveraging |

During and immediately following [[World War I]], a large population of [[African Americans]] emigrated from the [[South]] to the [[North]] and [[Midwest]] in search of job opportunities. The predominantly white-populated Midwest perceived the black migrant laborers as a threat to their employment, as well as to their ability to negotiate pay rates. [[US Steel]], for instance, the most important regional employer, addressed labor concerns by leveraging black laborers, migrants from the South.<ref name=doc /> |

||

This racial antagonism erupted into [[race riots]] across the North and Midwest in 1919; this period of widespread flourishes of violence became known as the [[Red Summer of 1919]]. Even after the riots subsided, racial relations between blacks and whites remained strained and volatile. |

This racial antagonism erupted into [[race riots]] across the North and Midwest in 1919; this period of widespread flourishes of violence became known as the [[Red Summer of 1919]]. Even after the riots subsided, racial relations between blacks and whites remained strained and volatile. |

||

Revision as of 00:38, 10 June 2009

The Duluth Lynchings occurred on June 15, 1920, when three black circus workers were attacked and lynched by a mob in Duluth, Minnesota. Rumors had circulated among the mob that six blacks had raped a teenage girl. A physician's examination subsequently found no evidence of rape or assault.[1][2]

The killings shocked the country, particularly for their having occurred in the northern United States.[3] In 2003, the city of Duluth erected a memorial to the murdered workers.

Background

During and immediately following World War I, a large population of African Americans emigrated from the South to the North and Midwest in search of job opportunities. The predominantly white-populated Midwest perceived the black migrant laborers as a threat to their employment, as well as to their ability to negotiate pay rates. US Steel, for instance, the most important regional employer, addressed labor concerns by leveraging black laborers, migrants from the South.[1]

This racial antagonism erupted into race riots across the North and Midwest in 1919; this period of widespread flourishes of violence became known as the Red Summer of 1919. Even after the riots subsided, racial relations between blacks and whites remained strained and volatile.

Event

On June 14, 1920, the James Robinson Circus arrived in Duluth for a performance. Two local teenagers, Irene Tusken, age nineteen, and James Sullivan, eighteen, met at the circus and ended up behind the big top, watching the black workers dismantle the menagerie tent, load wagons and generally get the circus ready to move on. What actual events that transpired between Tusken, Sullivan and the workers are unknown; however, later that night Sullivan claimed that he and Tusken were assaulted, and Tusken was raped by five or six black circus workers. In the early morning of June 15th, Duluth Police Chief John Murphy received a call from James Sullivan’s father saying six black circus workers had held the pair at gunpoint and then raped Irene Tusken. John Murphy then lined up all 150 or so roustabouts, food service workers and props-men on the side of the tracks, and asked Sullivan and Tusken to identify their attackers. The police arrested six black men in connection with the rape. The authenticity of Sullivan's rape claim is subject to skepticism. When Tusken was examined by her physician, Dr. David Graham, on the morning of June 15, he found no physical evidence of rape or assault.[2]

Newspapers printed articles on the alleged rape, while rumors spread throughout the town that Tusken had died as a result of the assault. Through the course of the day, a mob estimated between 5,000 and 10,000 people[2] formed outside the Duluth city jail and broke into the jail to beat and hang the accused. The Duluth Police, ordered not to use their guns, offered little or no resistance to the mob. The mob seized Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie and found them guilty of Tusken's rape in a sham trial. The three men were taken to 1st Street and 2nd Avenue East,[2] where they were lynched by the mob.

The next day the Minnesota National Guard arrived at Duluth to secure the area and to guard the surviving prisoners, as well as nine other men who were suspected. They were moved to the St. Louis County Jail under heavy guard.[2]

Aftermath

The killings made headlines throughout the country. Many were shocked such an atrocity happened in Minnesota, a northern state. The Chicago Evening Post opined, "This is a crime of a Northern state, as black and ugly as any that has brought the South in disrepute. The Duluth authorities stand condemned in the eyes of the nation." An article in the Minneapolis Journal accused the lynch mob of putting a "stain on the name of Minnesota," stating, "The sudden flaming up of racial passion, which is the reproach of the South, may also occur, as we now learn in the bitterness of humiliation in Minnesota."[2]

The June 15, 1920, Ely Miner reported that just across the bay in Superior, Wisconsin, the acting chief of police declared, "We are going to run all idle negroes out of Superior and they’re going to stay out." How many were forced out is not certain, but all of the blacks employed by a carnival in Superior were fired and told to leave the city.[2]

In its comprehensive site about the lynchings, the Minnesota State Historical Society reports the legal aftermath of the incident:

- Two days later on June 17, 1920, Judge William Cant and the grand jury had a difficult time convicting the lead mob members. In the end the grand jury issued thirty-seven indictments for the lynching mob and twenty-five were given out for rioting and twelve for the crime of murder in the first degree. Some of the people were indicted for both. But only 3 people would end up being convicted for rioting. Seven men were indicted for rape. For five of the indicted men, charges were dismissed. The remaining two, Max Mason and William Miller, were tried for rape. William Miller was acquitted, while Max Mason was convicted and sentenced to serve seven to thirty years in prison.”[2]

Mason served a prison sentence in Stillwater State Prison of only four years from 1921 to 1925 on the condition that he would leave the state.

No one was ever convicted for the murder of Isaac McGhie, Elmer Jackson and Elias Clayton.

Memorial

On October 10, 2003 the event was commemorated in Duluth, by dedicating a plaza including three 7-foot-tall bronze statues to the three men who were killed. The statues are part of a memorial across the street from the site of the lynchings. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial is the largest lynching monument in the United States.[4]

At the memorial's opening, thousands of citizens of Duluth and surrounding communities gathered for a ceremony. The final speaker at the ceremony was Warren Read, the great-grandson of one of the most prominent leaders of the lynch mob:

It was a long held family secret, and its deeply buried shame was brought to the surface and unraveled. We will never know the destinies and legacies these men would have chosen for themselves if they had been allowed to make that choice. But I know this: their existence however brief and cruelly interrupted is forever woven into the fabric of my own life. My son will continue to be raised in an environment of tolerance, understanding and humility, now with even more pertinence than before.

— [1]

Read has written a memoir exploring his experiences with this discovery, as well his journey to find and connect with the descendants of Elmer Jackson, one of the men lynched that night. His book will be released through Borealis Books in March 2008.[5]

Popular culture

The first verse of Bob Dylan's 1965 song Desolation Row recalls the lynchings in Duluth:

They're selling postcards of the hanging

They're painting the passports brown

The beauty parlor is filled with sailors

The circus is in town

Here comes the blind commissioner

They've got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad they're restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row[1]

Dylan was born in Duluth and spent his early years there. His father, Abram Zimmerman, was nine years old in June 1920 and lived two blocks from the site of the lynchings. Zimmerman passed the story on to his son.[6]

References

- ^ a b c d Duluth Lynchings: Presence of the Past. Twin Cities Public Television.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Duluth Lynchings On line Resource". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2006-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ MOVE TO PUNISH DULUTH LYNCHERS. New York Times. June 17, 1920.

- ^ Duluth Remembers 1920 Lynching. Tolerance.org. October 13, 2003.

- ^ The Lyncher in Me; A Search for Redemption in the Face of History. Read, Warren.

- ^ Hoekstra, Dave, "Dylan's Duluth Faces Up to Its Past," Chicago Sun-Times, July 1, 2001. "The family lived a couple of blocks away from the lynching site at what is now a parking lot at 221 Lake Ave. North." The connection is also made by Andrew Buncombe in a June 17, 2001, article in The Independent (London) — "'They're Selling Postcards of the Hanging...': Duluth's Day of Desolation Remembered."

- Fedo, Michael (2000). The Lynchings in Duluth. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-386-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Olsen, Ken. "Duluth Remembers 1920 Lynching". Fight Hate and Promote Tolerance. Tolerance.org. Retrieved 2006-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=and|coauthors=(help)