Thales's theorem: Difference between revisions

add trig proof |

Changing "two right angles" to 180° for clarity |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

There is nothing extant of the writing of Thales; work done in ancient Greece tended to be attributed to men of wisdom without respect to all the individuals involved in any particular intellectual constructions — this is true of Pythagoras especially. Attribution did tend to occur at a later time.<ref>G.Donald Allen - [[Texas University]] [http://www.math.tamu.edu/ Department of Mathematics] [http://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/masters/Greek/thales.pdf edu] Retrieved 2012-02-12</ref> Reference to Thales was made by Proclus, and by Diogenes Laertius documenting Pamphila statement that the ancient <ref name="Poetics">Prof.T.Patronis & D.Patsopoulos {{cite book | url =http://journals.tc-library.org/index.php/hist_math_ed/article/viewFile/189/184 | title = The Theorem of Thales: A Study of the naming of theorems in school Geometry textbooks | publisher = [[Patras University]] | accessdate = 2012-02-12}}</ref>{{cquote| was the first to ascribe a right-angle triangle within a circle <ref name="Poetics"/> (Thomas 2002) }} |

There is nothing extant of the writing of Thales; work done in ancient Greece tended to be attributed to men of wisdom without respect to all the individuals involved in any particular intellectual constructions — this is true of Pythagoras especially. Attribution did tend to occur at a later time.<ref>G.Donald Allen - [[Texas University]] [http://www.math.tamu.edu/ Department of Mathematics] [http://www.math.tamu.edu/~dallen/masters/Greek/thales.pdf edu] Retrieved 2012-02-12</ref> Reference to Thales was made by Proclus, and by Diogenes Laertius documenting Pamphila statement that the ancient <ref name="Poetics">Prof.T.Patronis & D.Patsopoulos {{cite book | url =http://journals.tc-library.org/index.php/hist_math_ed/article/viewFile/189/184 | title = The Theorem of Thales: A Study of the naming of theorems in school Geometry textbooks | publisher = [[Patras University]] | accessdate = 2012-02-12}}</ref>{{cquote| was the first to ascribe a right-angle triangle within a circle <ref name="Poetics"/> (Thomas 2002) }} |

||

[[Indian mathematics|Indian]] and [[Babylonian mathematics|Babylonian mathematician]]s knew this for special cases before Thales proved it.<ref>de Laet, Siegfried J. (1996). ''History of Humanity: Scientific and Cultural Development''. [[UNESCO]], Volume 3, p. 14. ISBN 92-3-102812-X</ref> It is believed that Thales learned that an angle inscribed in a semicircle is a right angle during his travels to [[Babylon]].<ref>Boyer, Carl B. and Merzbach, Uta c. (2010). ''A History of Mathematics''. John Wiley and Sons, Chapter IV. ISBN 0-470-63056-6</ref> The theorem is named after Thales because he was said by ancient sources to have been the first to prove the theorem, using his own results that the base angles of an [[isosceles triangle]] are equal, and that the sum of angles in a triangle is equal to |

[[Indian mathematics|Indian]] and [[Babylonian mathematics|Babylonian mathematician]]s knew this for special cases before Thales proved it.<ref>de Laet, Siegfried J. (1996). ''History of Humanity: Scientific and Cultural Development''. [[UNESCO]], Volume 3, p. 14. ISBN 92-3-102812-X</ref> It is believed that Thales learned that an angle inscribed in a semicircle is a right angle during his travels to [[Babylon]].<ref>Boyer, Carl B. and Merzbach, Uta c. (2010). ''A History of Mathematics''. John Wiley and Sons, Chapter IV. ISBN 0-470-63056-6</ref> The theorem is named after Thales because he was said by ancient sources to have been the first to prove the theorem, using his own results that the base angles of an [[isosceles triangle]] are equal, and that the sum of angles in a triangle is equal to 180°. |

||

{{quotebox|width=33% |

{{quotebox|width=33% |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

===First proof=== |

===First proof=== |

||

We use the following facts: the sum of the angles in a [[triangle]] is equal to |

We use the following facts: the sum of the angles in a [[triangle]] is equal to 180[[degree (angle)|°]] and the base angles of an [[isosceles triangle]] are equal. |

||

{{Gallery |

{{Gallery |

||

|File:Animated illustration of thales theorem.gif|Provided ''AC'' is a [[diameter]], angle at ''B'' is constant [[right angle|right]] (90°). |

|File:Animated illustration of thales theorem.gif|Provided ''AC'' is a [[diameter]], angle at ''B'' is constant [[right angle|right]] (90°). |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Since OA = OB = OC, OBA and OBC are isosceles triangles, and by the equality of the base angles of an isosceles triangle, OBC = OCB and BAO = ABO. |

Since OA = OB = OC, OBA and OBC are isosceles triangles, and by the equality of the base angles of an isosceles triangle, OBC = OCB and BAO = ABO. |

||

Let [[Α#Math_and_science|α]] = BAO and [[Β#Math_and_science|β]] = OBC. The three internal angles of the ABC triangle are α, α + β and β. Since the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to |

Let [[Α#Math_and_science|α]] = BAO and [[Β#Math_and_science|β]] = OBC. The three internal angles of the ABC triangle are α, α + β and β. Since the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to 180°, we have |

||

:<math>\alpha+\left( \alpha + \beta \right) + \beta = 180^\circ </math> |

:<math>\alpha+\left( \alpha + \beta \right) + \beta = 180^\circ </math> |

||

Revision as of 02:57, 21 June 2013

In geometry, Thales' theorem (named after Thales of Miletus) states that if A, B and C are points on a circle where the line AC is a diameter of the circle, then the angle ABC is a right angle. Thales' theorem is a special case of the inscribed angle theorem, and is mentioned and proved on the 33rd proposition, third book of Euclid's Elements. It is generally attributed to Thales, who is said to have sacrificed an ox in honor of the discovery, but sometimes it is attributed to Pythagoras.

History

There is nothing extant of the writing of Thales; work done in ancient Greece tended to be attributed to men of wisdom without respect to all the individuals involved in any particular intellectual constructions — this is true of Pythagoras especially. Attribution did tend to occur at a later time.[1] Reference to Thales was made by Proclus, and by Diogenes Laertius documenting Pamphila statement that the ancient [2]

was the first to ascribe a right-angle triangle within a circle [2] (Thomas 2002)

Indian and Babylonian mathematicians knew this for special cases before Thales proved it.[3] It is believed that Thales learned that an angle inscribed in a semicircle is a right angle during his travels to Babylon.[4] The theorem is named after Thales because he was said by ancient sources to have been the first to prove the theorem, using his own results that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal, and that the sum of angles in a triangle is equal to 180°.

- o se del mezzo cerchio far si puote

- triangol sì ch'un retto non avesse.

- Or if in semicircle can be made

- Triangle so that it have no right angle.

Dante's Paradiso, Canto 13, lines 101–102. English translation by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Dante's Paradiso (canto 13, lines 101–102) refers to Thales' theorem in the course of a speech.

Proof

First proof

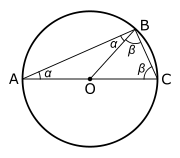

We use the following facts: the sum of the angles in a triangle is equal to 180° and the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal.

Since OA = OB = OC, OBA and OBC are isosceles triangles, and by the equality of the base angles of an isosceles triangle, OBC = OCB and BAO = ABO.

Let α = BAO and β = OBC. The three internal angles of the ABC triangle are α, α + β and β. Since the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to 180°, we have

Second proof

The theorem may also be proven using trigonometry: Let , , and . Then B is a point on the unit circle . We will show that ABC forms a right angle by proving that AB and BC are perpendicular — that is, the product of their slopes is equal to –1. We calculate the slopes for AB and BC:

and

Then we show that their product equals –1:

which is true by the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

Converse

The converse of Thales' theorem is also valid; it states that a right triangle's hypotenuse is a diameter of its circumcircle.

Combining Thales' theorem with its converse we get that:

- The center of a triangle's circumcircle lies on one of the triangle's sides if and only if the triangle is a right triangle.

Proof of the converse using geometry

This proof consists of 'completing' the right triangle to form a rectangle and noticing that the center of that rectangle is equidistant from the vertices and so is the center of the circumscribing circle of the original triangle, it utilizes two facts:

- adjacent angles in a parallelogram are supplementary (add to 180°) and,

- the diagonals of a rectangle are equal and cross each other in their median point.

Let there be a right angle ABC, r a line parallel to BC passing by A and s a line parallel to AB passing by C. Let D be the point of intersection of lines r and s (Note that it has not been proven that D lies on the circle)

The quadrilateral ABCD forms a parallelogram by construction (as opposite sides are parallel). Since in a parallelogram adjacent angles are supplementary (add to 180°) and ABC is a right angle (90°) then angles BAD, BCD, and ADC are also right (90°); consequently ABCD is a rectangle.

Let O be the point of intersection of the diagonals AC and BD. Then the point O, by the second fact above, is equidistant from A,B, and C. And so O is center of the circumscribing circle, and the hypotenuse of the triangle AC is a diameter of the circle.

Proof of the converse using linear algebra

This proof utilizes two facts:

- two lines form a right angle if and only if the dot product of their directional vectors is zero, and

- the square of the length of a vector is given by the dot product of the vector with itself.

Let there be a right angle ABC and circle M with AC as a diameter. Let M's center lie on the origin, for easier calculation. Then we know

- A = − C, because the circle centered at the origin has AC as diameter, and

- (A − B) · (B − C) = 0, because ABC is a right angle.

It follows

- 0 = (A − B) · (B − C) = (A − B) · (B + A) = |A|2 − |B|2.

Hence:

- |A| = |B|.

This means that A and B are equidistant from the origin, i.e. from the center of M. Since A lies on M, so does B, and the circle M is therefore the triangle's circumcircle.

The above calculations in fact establish that both directions of Thales' theorem are valid in any inner product space.

Thales' theorem is a special case of the following theorem:

- Given three points A, B and C on a circle with center O, the angle AOC is twice as large as the angle ABC.

See inscribed angle, the proof of this theorem is quite similar to the proof of Thales' theorem given above.

A related result to Thales' theorem is the following:

- If AC is a diameter of a circle, then:

- If B is inside the circle, then ∠ABC > 90°

- If B is on the circle, then ∠ABC = 90°

- If B is outside the circle, then ∠ABC < 90°.

Application

Thales' theorem can be used to construct the tangent to a given circle that passes through a given point. (See figure.) Given a circle k, with a center O, and a point P outside of the circle, we want to construct the (red) tangent(s) to k that pass through P. Suppose the (as yet unknown) tangent t touches the circle in the point T. From symmetry, it is clear that the radius OT is orthogonal to the tangent. So construct the midpoint H between O and P, and draw a circle centered at H through O and P. By Thales' theorem, the sought point T is the intersection of this circle with the given circle k, because that is the point on k that completes a right triangle OTP.

Since the two circles intersect at two points, we can construct both tangents in this fashion.

See also

References

- Agricola, Ilka; Friedrich, Thomas (2008). Elementary Geometry. AMS. p. 50. ISBN 0-8218-4347-8. (restricted online copy, p. 50, at Google Books)

- Heath, T.L. (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics: From Thales to Euclid. Vol. I. Oxford. pp. 131ff.

- ^ G.Donald Allen - Texas University Department of Mathematics edu Retrieved 2012-02-12

- ^ a b Prof.T.Patronis & D.Patsopoulos The Theorem of Thales: A Study of the naming of theorems in school Geometry textbooks. Patras University. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- ^ de Laet, Siegfried J. (1996). History of Humanity: Scientific and Cultural Development. UNESCO, Volume 3, p. 14. ISBN 92-3-102812-X

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. and Merzbach, Uta c. (2010). A History of Mathematics. John Wiley and Sons, Chapter IV. ISBN 0-470-63056-6

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Thales' Theorem". MathWorld.

- Munching on Inscribed Angles

- Thales' theorem explained With interactive animation

- Thales' Theorem by Michael Schreiber, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.