Arithmetic shift: Difference between revisions

m Image Rotate left logically.svg depicts a logic shift and is shown in the the page LOGICAL SHIFT.Edits are made to the caption explaining the same. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!--This article is in Commonwealth English--> |

<!--This article is in Commonwealth English--> |

||

[[Image:Rotate left logically.svg|thumb|300px|A left logical shift of a binary number by 1. The empty position in the [[least significant bit]] is filled with a zero |

[[Image:Rotate left logically.svg|thumb|300px|A left logical shift of a binary number by 1. The empty position in the [[least significant bit]] is filled with a zero.]] |

||

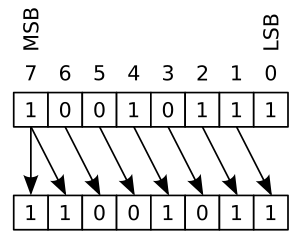

[[Image:Rotate right arithmetically.svg|thumb|300px|A right arithmetic shift of a binary number by 1. The empty position in the most significant bit is filled with a copy of the original MSB.]] |

[[Image:Rotate right arithmetically.svg|thumb|300px|A right arithmetic shift of a binary number by 1. The empty position in the most significant bit is filled with a copy of the original MSB.]] |

||

Revision as of 16:45, 10 November 2013

| Language | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| VHDL, MIPS | sla[note 1] | sra |

| Verilog | <<< | >>>[note 2] |

| C/C++/Go (signed types only)[note 3] | << | >> |

| Java, JavaScript, Python, PHP, Ruby, etc. | << | >> |

| OpenVMS macro language | @[note 4] | |

| Scheme | arithmetic-shift[note 5] | |

| Common Lisp | ash | |

| OCaml | lsl | asr |

| Standard ML | << | ~>> |

| Haskell | shiftL | shiftR |

| x86 Assembly | SAL | SAR |

| Action Script 3 | << | >> |

In computer programming, an arithmetic shift is a shift operator, sometimes known as a signed shift (though it is not restricted to signed operands). The two basic flavours are the arithmetic left shift and the arithmetic right shift. For binary numbers it is a bitwise operation that shifts all of the bits of its operand; every bit in the operand is simply moved a given number of bit positions, and the vacant bit-positions are filled in. Instead of being filled with all 0s, as in logical shift, when shifting to the right, the leftmost bit (usually the sign bit in signed integer representations) is replicated to fill in all the vacant positions (this is a kind of sign extension).

Arithmetic shifts can be useful as efficient ways of performing multiplication or division of signed integers by powers of two. Shifting left by n bits on a signed or unsigned binary number has the effect of multiplying it by 2n. Shifting right by n bits on a two's complement signed binary number has the effect of dividing it by 2n, but it always rounds down (towards negative infinity). This is different from the way rounding is usually done in signed integer division (which rounds towards 0). This discrepancy has led to bugs in more than one compiler. [2]

For example, in the x86 instruction set, the SAR instruction (arithmetic right shift) divides a signed number by a power of two, rounding towards negative infinity.[3] However, the IDIV instruction (signed divide) divides a signed number, rounding towards zero. So a SAR instruction cannot be substituted for an IDIV by power of two instruction nor vice versa.

Formal definition

The formal definition of an arithmetic shift, from Federal Standard 1037C is that it is:

- A shift, applied to the representation of a number in a fixed radix numeration system and in a fixed-point representation system, and in which only the characters representing the fixed-point part of the number are moved. An arithmetic shift is usually equivalent to multiplying the number by a positive or a negative integral power of the radix, except for the effect of any rounding; compare the logical shift with the arithmetic shift, especially in the case of floating-point representation.

An important word in the FS 1073C definition is "usually".

Equivalence of arithmetic left shift and multiplication

Arithmetic left shifts are equivalent to multiplication by a (positive, integral) power of the radix (e.g. a multiplication by a power of 2 for binary numbers). Arithmetic left shifts are, with two exceptions, identical in effect to logical left shifts. The first exception is the minor trap that arithmetic shifts may trigger arithmetic overflow whereas logical shifts do not. Obviously that exception only hits in real world use cases if a trigger signal for such an overflow is needed by the design it's used for. The second exception is the MSB is preserved. Processors typically do not offer logical and arithmetic left shift operations with a significant difference, if any.

Non-equivalence of arithmetic right shift and division

However, arithmetic right shifts are major traps for the unwary.

It is frequently stated that arithmetic right shifts are equivalent to division by a (positive, integral) power of the radix (e.g. a division by a power of 2 for binary numbers), and hence that division by a power of the radix can be optimized by implementing it as an arithmetic right shift. (A shifter is much simpler than a divider. On most processors, shift instructions will execute more quickly than division instructions.) Guy L. Steele quotes a large number of 1960s and 1970s programming handbooks, manuals, and other specifications from companies and institutions such as DEC, IBM, Data General, and ANSI that make such statements.[4][page needed] However, as Steele points out, they are all wrong.

Logical right shifts are equivalent to division by a power of the radix (usually 2) only for positive or unsigned numbers. Arithmetic right shifts are equivalent to logical right shifts for positive signed numbers. Arithmetic right shifts for negative numbers in N-1's complement (usually two's complement) is roughly equivalent to division by a power of the radix (usually 2), where for odd numbers rounding downwards is applied (not towards 0 as usually expected). (Arithmetic right shifts for negative numbers would be equivalent to division using rounding towards 0 in one's complement representation of signed numbers as was used by some historic computers.)

Handling the issue in programming languages

The (1999) ISO standard for the C programming language defines the C language's right shift operator in terms of divisions by powers of 2.[5] Because of the aforementioned non-equivalence, the standard explicitly excludes from that definition the right shifts of signed numbers that have negative values. It doesn't specify the behaviour of the right shift operator in such circumstances, but instead requires each individual C compiler to specify the behaviour of shifting negative values right.[note 6]

Notes

- ^ The VHDL arithmetic left shift operator is unusual. Instead of filling the LSB of the result with zero, it copies the original LSB into the new LSB. Whilst this is an exact mirror image of the arithmetic right shift, it is not the conventional definition of the operator, and is not equivalent to multiplication by a power of 2. In the VHDL 2008 standard this strange behavior was left unchanged (for backwards compatibility) for argument types that do not have forced numeric interpretation (e.g. BIT_VECTOR) but 'SLA' for unsigned and signed argument types behaves in the expected way (i.e. rightmost positions are filled with zeros). VHDL's SLL (Shift Left Logical) function does implement the aforementioned 'standard' arithmetic shift.

- ^ The Verilog arithmetic right shift operator only actually performs an arithmetic shift if the first operand is signed. If the first operand is unsigned, the operator actually performs a logical right shift.

- ^ The >> operator in C and C++ is not necessarily an arithmetic shift. Usually it is only an arithmetic shift if used with a signed integer type on its left-hand side. If it is used on an unsigned integer type instead, it will be a logical shift.

- ^ In the OpenVMS macro language whether an arithmetic shift is a left or a right shift is determined by whether the second operand is positive or negative. This is unusual. In most programming languages the two directions have distinct operators, with the operator specifying the direction, and the second operand is implicitly positive. (Some languages, such as Verilog, require that negative values be converted to unsigned positive values. Some languages, such as C and C++, do not have defined behaviours if negative values are used.)[1][page needed]

- ^ In Scheme arithmetic-shift can be both left and right shift, depending on the second operand, very similar to the OpenVMS macro language, although R6RS Scheme adds both -right and -left variants.

- ^ The C standard was intended to not restrict the C language to either ones' complement or two's complement architectures. In cases where the behaviours of ones' complement and two's complement representations differ, such as this, the standard requires individual C compilers to document the actual behaviour of their target architectures. The documentation for GCC, for example, documents its behaviour as employing sign-extension.[6]

References

Cross-reference

- ^ HP 2001.

- ^ Steele Jr, Guy. "Arithmetic Shifting Considered Harmful" (PDF). MIT AI Lab. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Hyde 1996, § 6.6.2.2 SAR.

- ^ Steele 1977.

- ^ ISOIEC9899 1999, § 6.5.7 Bitwise shift operators.

- ^ FSF 2008, § 4.5 Integers implementation.

Sources used

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

- Knuth, Donald (1969). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2 — Seminumerical algorithms. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. pp. 169–170.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Steele, Guy L. (1977). "Arithmetic shifting considered harmful". ACM SIGPLAN Notices archive. 12 (11). New York: ACM Press: 61–69. doi:10.1145/956641.956647.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "VAX MACRO and Instruction Set Reference Manual". HP OpenVMS Systems Documentation. Hewlett-Packard Development Company. 2001.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Programming languages — C". ISO/IEC 9899:1999. International Organization for Standardization. 1999.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hyde, Randall (1996-09-26). "CHAPTER SIX: THE 80x86 INSTRUCTION SET (Part 3)". The Art of ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "C Implementation". GCC manual. Free Software Foundation. 2008.