Bang–bang control: Difference between revisions

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Mathematically or within a computing context there may |

Mathematically or within a computing context there may |

||

be no problems, but the physical realization of bang-bang |

be no problems, but the physical realization of bang-bang |

||

control systems gives rise to several complications. |

control systems gives rise to several complications. First, depending on the width of the hysteresis gap and inertia in the process, there will be an oscillating error signal around the desired set point value (e.g., temperature), often saw-tooth shaped. Room temperature may become uncomfortable just before the next switch 'ON' event. |

||

Second, the onset of the step function may entail, e.g., a high electrical current and/or sudden heating and expansion of metal vessels, ultimately leading to [[metal fatigue]] or other wear and tear effects. Where possible, continuous control, such as in [[PID control]] will avoid problems caused by the brisk physical system state transitions that are the consequence of bang-bang control. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 10:22, 2 February 2017

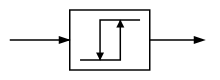

In control theory, a bang–bang controller (on–off controller), also known as a hysteresis controller, is a feedback controller that switches abruptly between two states. These controllers may be realized in terms of any element that provides hysteresis. They are often used to control a plant that accepts a binary input, for example a furnace that is either completely on or completely off. Most common residential thermostats are bang–bang controllers. The Heaviside step function in its discrete form is an example of a bang–bang control signal. Due to the discontinuous control signal, systems that include bang–bang controllers are variable structure systems, and bang–bang controllers are thus variable structure controllers.

Bang–bang solutions in optimal control

In optimal control problems, it is sometimes the case that a control is restricted to be between a lower and an upper bound. If the optimal control switches from one extreme to the other (i.e., is strictly never in between the bounds), then that control is referred to as a bang-bang solution.

Bang–bang controls frequently arise in minimum-time problems. For example, if it is desired to stop a car in the shortest possible time at a certain position sufficiently far ahead of the car, the solution is to apply maximum acceleration until the unique switching point, and then apply maximum braking to come to rest exactly at the desired position.

A familiar everyday example is bringing water to a boil in the shortest time, which is achieved by applying full heat, then turning it off when the water reaches a boil. A closed-loop household example is most thermostats, wherein the heating element or air conditioning compressor is either running or not, depending upon whether the measured temperature is above or below the setpoint.

Bang–bang solutions also arise when the Hamiltonian is linear in the control variable; application of Pontryagin's minimum or maximum principle will then lead to pushing the control to its upper or lower bound depending on the sign of the coefficient of u in the Hamiltonian.

In summary, bang–bang controls are actually optimal controls in some cases, although they are also often implemented because of simplicity or convenience.

Practical implications of bang-bang control

Mathematically or within a computing context there may be no problems, but the physical realization of bang-bang control systems gives rise to several complications. First, depending on the width of the hysteresis gap and inertia in the process, there will be an oscillating error signal around the desired set point value (e.g., temperature), often saw-tooth shaped. Room temperature may become uncomfortable just before the next switch 'ON' event.

Second, the onset of the step function may entail, e.g., a high electrical current and/or sudden heating and expansion of metal vessels, ultimately leading to metal fatigue or other wear and tear effects. Where possible, continuous control, such as in PID control will avoid problems caused by the brisk physical system state transitions that are the consequence of bang-bang control.

See also

- Euler equation

- Double-setpoint control

- Lyapunov's theorem

- Optimal control

- Robust control

- Sliding mode control

- Vector measure

- Pulse and glide

- GBU-12 Paveway II

References

- Template:Cite article

- Hermes, Henry; LaSalle, Joseph P. (1969). Functional analysis and time optimal control. Mathematics in Science and Engineering. Vol. 56. New York—London: Academic Press. pp. viii+136. MR 0420366.

- Kluvánek, Igor; Knowles, Greg (1976). Vector measures and control systems. North-Holland Mathematics Studies. Vol. 20. New York: North-Holland Publishing Co. pp. ix+180. MR 0499068.

- Rolewicz, Stefan (1987). Functional analysis and control theory: Linear systems. Mathematics and its Applications (East European Series). Vol. 29 (Translated from the Polish by Ewa Bednarczuk ed.). Dordrecht; Warsaw: D. Reidel Publishing Co.; PWN—Polish Scientific Publishers. pp. xvi+524. ISBN 90-277-2186-6. MR 0920371. OCLC 13064804Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Sonneborn, L.; Van Vleck, F. (1965). "The Bang-Bang Principle for Linear Control Systems". SIAM J. Control. 2: 151–159Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)