Ebbo Gospels

The Ebbo Gospels (Épernay, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 1) is an early Carolingian illuminated Gospel book known for its illustrations that appear agitated. The book was produced in the ninth century at the Benedictine Abbaye Saint-Pierre d’Hautvillers. Its style influenced Carolingian art and the course of medieval art (Berenson, 165).

Date

The Gospel book contains a poem to Ebbo (also spelled Ebo), and so is dated within the time he was archbishop, usually to the period c. 816-835 before he was deposed. Ebbo also held Rheims from 840-841 and the Gospel book may have been made for his return (Chazelle, 1074).

Style

Each page is 10 in by 8 in. The illustrations have roots in late classical painting; landscapes are represented in an illusionistic style. Greek artists fleeing the Byzantine iconoclasm of the 8th century brought this style to Aachen and Reims (Berenson, 163).

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

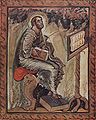

The emotionalism, however, was new to Carolingian art and distinguishes the Ebbo Gospels from classical art. Figures are represented in nervous, agitated poses using a streaky style with swift brush strokes. The Utrecht Psalter is the most famous example of this school (Berenson, 163). Calkins (p.211) mentions the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (870) as another manuscript following this style.

Commentators have noted the similarity between the Utrecht Psalter and the Ebbo Gospels. The evangelist portrait of Matthew in the Ebbo Gospels is similar to the illustration of the psalmist in the first psalm of the Utrecht Psalter (Benson, 23; Chazelle, 1073). Other images in the Ebbo Gospels appear to be based on distortions of drawings which may have been from the Utrecht Psalter (Chazelle 1074). According to Goldschmidt (cited in Benson, 23):

In short, we find not one thing, whether it is a stool with a lion's head and claws, or an inkwell, whether it is the lance or the arrow of the warrior, the lions, the birds, the buildings, the figures, and the gestures that cannot be paralleled to the smallest detail in style as well as in content, in the Utrecht Psalter.

References

- Benson, Gertrude R. (March 1931). "New light on the origin of the Utrecht Psalter". The Art Bulletin. 13 (1): 13–79. doi:10.1080/00043079.1931.11409295. JSTOR 3045474.

- Berenson, Ruth (Winter 1966–1967). "The Exhibition of Carolingian art at Aachen". Art Journal. 26 (2): 160–165. doi:10.2307/775040. JSTOR 775040.

- Calkins, Robert G. (1983). Illuminated books of the middle ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9377-3.

- Chazelle, Celia (October 1997). "Archbishops Ebo and Hincmar of Reims and the Utrecht Psalter". Speculum. 72 (4): 1055–1077. doi:10.2307/2865958. JSTOR 2865958.

- Ross, Nancy, Carolingian Art, Smarthistory, undated