Right-to-work law

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Right-to-work laws are statutes enforced in twenty two U.S. States, allowed under provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act, which prohibit trade unions from making membership or payment of dues or "fees" a condition of employment, either before or after hire.

The Taft-Hartley Act

Prior to the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act by Congress over President Harry S. Truman's veto in 1947, unions and employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act could lawfully agree to a "closed shop," in which employees at unionized workplaces are required to be members of the union as a condition of employment. Under the law in effect before the Taft-Hartley amendments, an employee who ceased being a member of the union for whatever reason, from failure to pay dues to expulsion from the union as an internal disciplinary punishment, could also be fired even if the employee did not violate any of the employer's rules.

The Taft-Hartley Act outlaws the "closed shop." The Act, however, permits employers and unions to operate under a "union shop" rule, which requires all new employees to join the union after a minimum period after their hire. Under "union shop" rules, employers are obliged to fire any employees who have avoided paying membership dues necessary to maintain membership in the union; however, the union cannot demand that the employer discharge an employee who has been expelled from membership for any other reason.

A similar arrangement to the "union shop" is the "agency shop," under which employees must pay the equivalent of union dues, but does not require them to formally join the union.

Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act goes further and authorizes individual states (but not local governments, such as cities or counties) to outlaw the union shop and agency shop for employees working in their jurisdictions. Under the "open shop" rule, an employee cannot be compelled to join or pay the equivalent of dues to a union that may exist at the employer, nor can the employee be fired if s/he joins the union. In other words, the employee has the "right to work," whether as a union member or not whether they contribute financially to the union or not.

The Federal Government operates under "open shop" rules nationwide, although many of its employees are represented by unions. Conversely, professional sports leagues (regardless of where a team is located) operate under "union shop" rules.

Arguments for and against right-to-work laws

Arguments for right-to-work laws

Proponents of right-to-work laws point to the Constitutional right to freedom of association, as well as the common-law principle of private ownership of property. They argue that workers should be free both to join unions and to refrain from joining unions, and for this reason often refer to non-right-to-work states as "forced-union" states. They contend that it is wrong for unions to be able to force employers to include clauses in their union contracts which require all employees to either join the union, or pay union dues as a condition of employment. Furthermore, they contend that in certain cases "forced union dues" are used to make significant contributions to support political causes, causes which many union members may oppose.

Proponents also point to the advantage of a more efficient labor market, with more competitive businesses and better economic growth as a result.[citation needed]

Arguments against right-to-work laws

Opponents of right-to-work laws argue that the ability of non-union employees to benefit from collective bargaining without paying dues creates a free rider problem. Not allowing forced union membership, while still ostensibly benefiting from the actions of that union, makes union activities less sustainable. Opponents also argue that the laws prevent free contracts between unions and business owners, making it harder for unions to organize and less attractive for people to join a union. For these reasons, they often refer to non-right-to-work states as "free collective bargaining" states.

Opponents further argue that because unions are weakened by these laws, wages are lowered and worker safety and health is endangered. They cite statistics from the United States Department of Labor showing, for example, that in 2003 the rate of workplace fatalities per 100,000 workers was highest in right-to-work states. 19 of the top 25 states for worker fatality rates were right-to-work states, while 3 of the bottom 25 states were right-to-work states. A 2001 study by the union-funded Economic Policy Institute showed that workers in right-to-work states earned an average of 6.5% less (4% after controlling for regional costs of living) than their counterparts in states without the law.

Economic information

According to the United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, from 1993-2003 the percentage change in real personal income was 29% growth overall. The change in Right to Work States was 37% growth, while the change in "union shop" States was 26% growth. Also according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, while a larger "growth" was experienced in the "right-to-work" states, overall real personal income remained higher in the "union-shop" states.

According to the United States Census Bureau, from 1982-2001 the percentage change in manufacturing establishments was 1.5% loss overall. The change in Right to Work States was 7% growth, while the change in "union shop" States was 4.9% loss.

Also according to the U.S. Census Bureau, from 1993-2003 the percentage growth of people covered by private health insurance was 8.5% growth. The change in Right to Work States was 13.6% growth, while the change in "union-shop" States was 5.9% growth. Also according to the U.S. Census Bureau, while a larger "growth" was experienced in the "right-to-work" states, overall the number of those privately insured remained higher in the "union-shop" states.

According to both the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau, from 1991-2001 the percentage change in real value added per production worker was 11.1% growth overall. The change in Right to Work States was 17.1% growth, while the change in "union-shop" states was 8.4% growth. Also according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, while a larger "growth" was experienced in the "right-to-work" states, overall production remained higher in the "union-shop" states.

Nevertheless, differences of this kind would not necessarily indicate an advantage to either kind of policy. The difference in growth rates could logically relate to "right-to-work" in one of three ways. A first hypothesis is that right-to-work laws directly cause improved economic growth. If true, this hypothesis would imply that a state would enjoy improved economic growth if it were to adopt a right-to-work law. A second hypothesis is that right-to-work laws indirectly cause executives to choose to add jobs to right-to-work states rather than in states where closed shops are permitted. This hypothesis suggests that most states that have adopted right-to-work laws were wise to do so, but that whatever comparative advantage they hold would disappear if right-to-work laws spread to all other states, or if executives no longer perceived these laws as protecting their interests. The last hypothesis is that the trend of accelerated growth in right-to-work states has no real connection to the presence of right-to-work laws. On that view, any number of alternative causes may be evident: the spread of air conditioning in "sun belt" states allowing the transportation benefits of milder winters to become apparent, laxer environmental regulations in parts of the South, lower rates of taxation, etc.

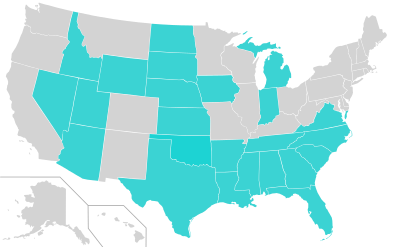

U.S. States with right-to-work laws

The following 22 states are right-to-work states:

- Alabama

- Arizona - (established by state's Constitution, not by statute)

- Arkansas - (established by state's Constitution, not by statute)

- Florida - (established by state's Constitution, not by statute)

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Louisiana

- Mississippi

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Oklahoma - (established by state's Constitution, not by statute)

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Wyoming

The territory of Guam also has right-to-work laws.

See also

References

External links

For "right-to-work" laws

- National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation

- National Right to Work Committee

- National Institute for Labor Relations Research

- Effects of Right to Work Laws on Employees, Unions and Businesses

- Union Free America