Aesop

Aesop (also spelled Æsop, from the Greek Αἴσωπος — Aisōpos), known only for the genre of fables ascribed to him, was by tradition a slave (δούλος) who was a contemporary of Croesus and Peisistratus in the mid-sixth century B.C. in ancient Greece. The various collections that go under the rubric "Aesop's Fables" are still taught as moral lessons and used as subjects for various entertainments, especially children's plays and cartoons. Most of what are known as Aesopic fables is a compilation of tales from various sources, many of which originated with authors who lived long before Aesop. The roots of fables go back all the way to India, where they were associated with Kasyapa, a mystical sage, and they were subsequently adopted by the early Buddhists. Nearly three hundred years later, some of these fables made their way to Alexandria. This collection introduced the use of the moral to sum up the teaching of a fable, which is similar to the “gatha” of the Jatakas. Aesop himself is said to have composed many fables, which were passed down by oral tradition. Socrates was thought to have spent his time turning Aesop’s fables into verse while he was in prison. Demetrius Phalereus, another Greek philosopher, made the first collection of these fables around 300 BCE. This was later translated into Latin by Phaedrus, a slave himself, around 25 BCE. The fables from these two collections were soon brought together and were eventually retranslated into Greek by Babrius around AD 230. Many additional fables were included, and the collection was in turn translated to Arabic and Hebrew, further enriched by additional fables from these cultures.

Life

The place of Aesop's birth was and still is disputed: Thrace, Phrygia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Samos, Athens, Sardis and Amorium all claimed the honour. It has been argued by modern writers that he may have been of African origin: the scholar Richard Lobban has argued that his name is likely derived from "Aethiopian", a word used by the Greeks to refer to all Sub-Saharan Africans. He continues by pointing out that the stories are populated by animals present in Africa, many of the creatures being quite foreign to Greece and Europe.[1]

The life of Aesop himself is shrouded in obscurity. He is said to have lived as a slave in Samos around 550 BCE. An ancient account of his life is found in The book of Xanthus the Philosopher and His Slave Aesop. According to the sparse information gathered about him from references to him in several Greek works (he was mentioned by Aristophanes, Plato, Xenophon and Aristotle), Aesop was a slave for someone called Xanthus (Ξανθος), who resided on the island of Samos. Aesop must have been freed, for he conducted the public defence of a certain Samian demagogue (Aristotle, Rhetoric, ii. 20). He subsequently lived at the court of Croesus, where he met Solon, and dined in the company of the Seven Sages of Greece with Periander at Corinth. During the reign of Peisistratus he was said to have visited Athens, where he told the fable of The Frogs Who Desired a King to dissuade the citizens from attempting to depose Peisistratus for another ruler. A contrary story, however, said that Aesop spoke up for the common people against tyranny through his fables, which incensed Peisistratus, who was against free speech.

According to the historian Herodotus, Aesop met with a violent death at the hands of the inhabitants of Delphi, though the cause was not stated. Various suggestions were made by later writers, such as his insulting sarcasms, the embezzlement of money entrusted to him by Croesus for distribution at Delphi, and his alleged sacrilege of a silver cup. A pestilence that ensued was blamed on his execution, and the Delphians declared their willingness to make compensation, which, in default of a nearer connection, was claimed by Iadmon (Ιάδμων), grandson of Aesop's former master.

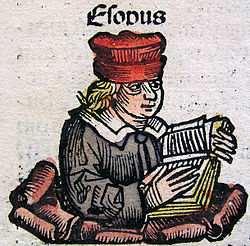

Popular stories surrounding Aesop were assembled in a vita prefixed to a collection of fables under his name, compiled by Maximus Planudes, a fourteenth-century monk. He was by tradition extremely ugly and deformed, which is the sole basis for making a grotesque marble figure in the Villa Albani, Rome, a "portrait of Aesop". This biography had actually existed a century before Planudes. It appeared in a thirteenth century manuscript found in Florence. However, according to another Greek historian Plutarch's account of the symposium of the Seven Sages, at which Aesop was a guest, there were many jests on his former servile status, but nothing derogatory was said about his personal appearance. Aesop's deformity was further disputed by the Athenians, who erected in his honour a noble statue by the sculptor Lysippus. Some suppose the sura, or "chapter," in the Qur'an titled Luqman to be referring to Aesop, a well-known figure in Arabia during the time of Muhammad.

Aesop was also briefly mentioned in the classic Egyptian myth, "The Girl and the Rose-Red Slippers", considered by many to be history's first Cinderella story. In the myth, the freed slave Rhodopis mentions that a slave named Aesop told her many entrancing stories and fables while they were slaves on the island of Samos.

Aesop's Fables

Aesop's Fables or the collection of fables assembled as Aesopica refers to various collections of moralized fables credited to Aesop. "Aesop's Fables" has also become a blanket term for collections of brief fables, usually involving personified animals. The Fox and the Grapes (from which the idiom "sour grapes" is derived), The Tortoise and the Hare, The North Wind and the Sun and The Shepherd Boy and the Wolf (also known as The Boy Who Cried Wolf), are well-known throughout the world.

French poet Jean de La Fontaine adapted many of the fables.

Russian writer Leo Tolstoy wrote free adaptations of some of his fables.

Sources

- Caxton, William, 1484. The history and fables of Aesop, Westminster. Modern reprint edited by Robert T. Lenaghan (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1967).

- Anthony, Mayvis, 2006. "The Legendary Life and Fables of Aesop", Mayant Press

- Bentley, Richard, 1697. Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris... and the Fables of Æsop. London.

- Compton, Todd, Victim of the Muses: Poet as Scapegoat, Warrior and Hero in Greco-Roman and Indo-European Myth and History. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies/Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 19-40.

- Jacobs, Joseph, 1889. The Fables of Aesop: Selected, Told Anew, and Their History Traced, as first printed by William Caxton, 1484, from his French translation

- i. A short history of the Aesopic fable

- ii. The Fables of Aesop

- Handford, S. A., 1954. Fables of Aesop. New York: Penguin.

- Holzberg, N., 2002. The Ancient Fable: An Introduction. Trans. by C. Jackson-Holzberg. Bloomington, IN.

- Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, pp. 280-90 in print edition.

- Perry, Ben E. (editor), 1965. Babrius and Phaedrus, (Loeb Classical Library) Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965. English translations of 143 Greek verse fables by Babrius, 126 Latin verse fables by Phaedrus, 328 Greek fables not extant in Babrius, and 128 Latin fables not extant in Phaedrus (including some medieval materials) for a total of 725 fables.

- Temple, Olivia and Robert (translators), 1998. Aesop, The Complete Fables, New York: Penguin Classics. (ISBN 0-14-044649-4)

- ^ Lobban, Richard. "Aesop." Historical dictionary of ancient and medieval Nubia. Scarecrow Press, c2004

External links

- Works by Aesop at Project Gutenberg

- Aesopica.net - Over 600 English fables, with Latin and Greek texts also - Searchable

- AesopFables.com - Large collection of fables, but many fables are NOT Aesopic

- Free audiobook of Aesop's Fables from LibriVox

- The Fables - A site primarily for children

- Stories that have been called "modern Aesop Fables"

- Aesop's Fables Illustrated - Simple, elegant illustrations to the Fables

- Carlson Fable Collection at Creighton University [[1]]

- Lesson plans incorporating the fables from Web English Teacher