Xkcd

| xkcd | |

|---|---|

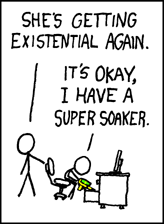

Panel from "Philosophy", with tooltip text "It's like the squirt bottle we use with the cat." | |

| Author(s) | Randall Munroe |

| Website | http://www.xkcd.com/ |

| Current status/schedule | Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays |

| Launch date | September 2005 |

| Genre(s) | Geek humor Men's romance |

xkcd is a webcomic created by Randall Munroe,[1] a Christopher Newport University graduate who worked as a contractor for NASA.[2] It calls itself "a webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language."[3][4] There is no particular meaning to the name,[4] which is simply a "treasured and carefully-guarded point in the space of four-character strings."[5]

The subjects of the comics themselves vary. Some are statements on life and love (some love strips are random art with poetry), and some are mathematical or scientific in-jokes. Some strips feature simple humor or pop-culture references. Although known for its crudely drawn cast of oddball stick figures,[6][1] the comic occasionally features landscapes, intricate mathematical patterns such as fractals, or imitations of the style of other cartoonists (as during "parody week"). Occasionally, realism is featured.[7][8]

The comic is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.[9] New comics are added three times a week, every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday,[2] at midnight[10] although so far they have been updated every weekday on three occasions: parody week, the five-part 'Choices' series and the 1337 series.

History

The comic began in September 2005 when Munroe decided to scan doodles from his school notebooks and put them on his webpage. Eventually the comic was changed into a standalone website, where Munroe started selling t-shirts based on the comic. He currently "works on the comic full time,"[4] making xkcd a self-sufficient webcomic.

In May 2007, the comic caught the attention of many by depicting online communities in geographic form.[11] Various websites were drawn as continents, each sized according to their relative popularity and located according to their general subject matter.[11] This put xkcd at number two on The Post-Standard's "The new hotness" list.[12]

xkcd is not an acronym, and Munroe attaches no meaning to the name, except in a joking manner within the comic.[13] He claims that the name was originally a screen name, which he selected as a combination of letters that would be meaningless, as well as phonetically unpronounceable.[4][2]

On September 23, 2007, hundreds of people gathered at coordinates mentioned in a strip: 42.39561 -71.13051. Fans converged on a park in North Cambridge, Massachusetts, where the strip's author appeared; among his comments: "Maybe wanting something does make it real," a reference to a frame in the same strip.[14][15]

In October of 2007, a group of researchers at University of Southern California Information Sciences Institute conducted a census of the internet and said that their data presentation was inspired by an xkcd comic.[16][17][18]

On April Fool's Day 2008, xkcd was part of a three-webcomic prank involving Dinosaur Comics and Questionable Content wherein each comic's URL displayed another comic's web page: questionablecontent.net displayed the Dinosaur Comics website, qwantz.com (the Dinosaur Comics website) displayed xkcd, and xkcd.com displayed the Questionable Content website. The prank was orchestrated by Randall Munroe, as Jeph Jacques announced on his website on April 2nd:

For those of you still baffled/alarmed by yesterday's little switcheroo, I remind you that it was April 1st. Thank you for all the well-intentioned "I think your site has been hacked!" emails. I can't take credit for the prank as it was Randall's idea, but it was too good not to take part in (also thanks Ryan for playing along and bearing the brunt of my readers' confusion).

Recurring themes

While there is no specific storyline to the comic, there are some recurring themes.[19] A large number of the strips are mathematics or computer science jokes. These jokes often feature university-level subjects, although many are written in such a way that a clear understanding of the subject is not usually required to get the punchline. Romance is another subject often visited in the comic, with many strips not intended to be humorous. xkcd frequently makes reference to Munroe's "obsession" with potential raptor attacks,[20][21][22][23][24] the game Guitar Hero,[25][26] characters making out with themselves,[27][28] and many "your mom" jokes. There have also been several strips featuring "Red Spiders", zeppelins, Joss Whedon's short-lived series Firefly, Ender's Game and Wikipedia.[29][30] Each comic has a tooltip, specified using the title attribute in HTML. The text usually contains an afterthought or annotation related to that day's comic.[31] There are also many strips depicting "My Hobby", usually depicting the non-descript narrator character describing some type of humorous or quirky behavior often involving language games.[19][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

Recurring characters

- A man in a hat who looks like a normal stick-figure xkcd character, except for the addition of his trademark black hat. Referring to himself as a "Classhole" (classy asshole), he is intolerant of internet newbishness. He does not shy from pointing out the foibles in others and has at times used extreme violence in order to emphasize a point. [42] [43] He is closely based on the character Aram from the Men In Hats webcomic.[44] In the January 30, 2008 comic, his hat was taken by a woman, who is, to date, the only person ever to foil one of his schemes. On April 2, 2008, he managed to track down the woman in a Russian submarine and take his hat back.[45]

- A boy in a barrel has appeared in 5 strips. Unlike most other characters, he is not a stick figure. He was repeatedly seen inside a barrel, floating in a large body of water. The boy in the barrel was one of many doodles in the older comics, but as of May 2008, has not been seen since comic #31.[46][47][48]

- Another set of recurring characters is the nihilist and the existentialist, recognizable by their hats; the existentialist wears a beret and the nihilist wears a white top hat (or no hat at all). So far, they have only been seen together, never separately. They can first be seen in the "Nihilism" comic, [49] and again in "Kayak",[50] "Hypotheticals"[51] and "Dignified."[52]

- Munroe is often a character himself, either identified explicitly as such onscreen[53] or narrating scenes occupied by unnamed characters[54] or no on-screen characters at all.[55]

- Fictionalised versions of well known real-life figures in the computing community sometimes appear, such as free software advocates Richard Stallman[56] [57] and Cory Doctorow.[58] [57]

- Mrs. Roberts was a main character in the "1337" series, and has appeared in other comics along with her children, "Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;--" aka "Little Bobby Tables," (a reference to SQL injection) [59] and "Help I'm Trapped In A Driver's License Factory Elaine Roberts", the protagonist of the "1337" series. Elaine's first name is a reference to "Pi Equals."[60]

Life imitates xkcd

On several occasions, fans have been motivated by Munroe's comics to carry out, in real life, the subject of a particular drawing or sketch. Some notable examples include:

- Richard Stallman was sent a katana[61] and was confronted by students dressed as ninjas before speaking at the Yale Political Union[62][63] – inspired by "Open Source"

- When Cory Doctorow won the 2007 EFF Pioneer Award, the presenters gave him a red cape, goggles and a balloon[64] – inspired by "Blagofaire"

- xkcd readers sneaking chess boards onto roller coasters[65][66] – inspired by "Chess Photo"

- An xkcd reader created a "MBR Love Note" installation program[67] – inspired by "Fight"

- Munroe himself solicited contributions from his readers of people playing electric guitars while in the shower on wetriffs.com[68] after posting the comic "Rule 34,"[69] in which a character registers that domain.

-

Cory Doctorow wears a red cape, goggles and a balloon as he receives the 2007 EFF Pioneer Award

Inspired by "Blagofaire"

References

- ^ a b Guzman, Monica. (May 11, 2007) Seattle Post-Intelligencer What's online. Section: Life and Arts; Page D7.

- ^ a b c Fernandez, Rebecca (2006-11-25). "xkcd: A comic strip for the computer geek". Red Hat Magazine. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ The Times (June 6, 2007) xkcd.com; The click; Wednesday. Section: Features; Page 2. (writing, "Web comics have thrived and one of the best is xkcd.com. The comic strip of "romance, sarcasm, math and language" is brilliant on the stupidity of people who comment on YouTube videos and, oddly, how we take dreaming in our stride: "I'm gonna go comatose for a few hours, hallucinate vividly, then maybe suffer amnesia about the whole experience."")

- ^ a b c d "About xkcd". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Best available explanation of the title". Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ Kalamazoo Gazette (August 17, 2006) Ad lib. Section: Ticket.

- ^ "The Cure (#56)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Girl sleeping (Sketch -- 11th grade Spanish class) (#7)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "License". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ xkcd » Blog Archive » Ghost

- ^ a b Tossell, Ivor. (May 18, 2007) Globe and Mail We're looking at each other, and it's not a pretty sight. Section: The Globe Review 7; Page R24

- ^ Cubbison, Brian; Thompson, Keith. (May 6, 2007) The Post-Standard. Get each of these links at the news tracker blog at blog.syracuse.com/Newstracker and remember, our blogs don't need www. our blogs start with blog. Section: News; Page A2.(Compiled from news services and online research by the authors)

- ^ "What xkcd Means (#207)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ Dream Girl (#240)

- ^ Cohen, Georgiana (September 26, 2007). "The wisdom of crowds". The Phoenix. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Paul McNamara (October 9, 2007). "Researchers ping through first full 'Internet census' in 25 years". Buzzblog. Networkworld.com. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ "62 Days + Almost 3 Billion Pings + New Visualization Scheme = the First Internet Census Since 1982". Information Science Institute. October 8, 2007 (Last modified October 9, 2007). Retrieved 2007-10-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|2=(help) - ^ "Map of the Internet (#195)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ a b Andrew Moses (November 21, 2007). "Former NASA staffer creates comics for geeks". The Gazette (University of Western Ontario). Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ^ O'Kane, Erin (2007-04-05). "Geek humor: Nothing to be ashamed of". The Whit Online. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ "Velociraptors (#87)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Substitute (#135)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Search History (#155)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Goto (#292)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ "Guitar Hero (#70)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Music Knowledge (#132)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Parallel Universe (#105)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Choices: Part 4(#267)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Wikipedian Protester (#285)". xkcd. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ "Getting Out of Hand (#333)". xkcd. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ Peter Trinh (2007-09-14). "A comic you can't pronounce". Imprint Online. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ^ "Hyphen(#37)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ "Hobby(#53)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Super Bowl(#60)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Curse Levels(#75)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Mispronouncing(#148)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Reverse Euphemisms(#168)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "That's What SHE Said(#174)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Collecting Double-Takes(#236)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Clichéd Exchanges(#259)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Keeping Time(#389)". xkcd. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "Words that End in GRY (#169)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Join Myspace (#146)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Hitler (#29)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Journal 3 (#405)". xkcd. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ "Barrel - Part 1 (#1)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ "Barrel - Part 2 (#11)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ "Barrel - Part 3 (#22)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ "Nihilism (#167)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ "Kayak (#209)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ^ "Hypotheticals (#248)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- ^ "Dignified (#291)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ "Snacktime Rules (#183)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ "Engineering Hubris (#319)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ "YouTube (#202)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ^ "Open Source (#225)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ a b "1337 Part 5 (#345)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ "Blagofaire (#239)". xkcd. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ "Exploits of a Mom". Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ "Pi Equals". Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ "Life Imitates xkcd, Part II: Richard Stallman". xkcd. 2007-04-19. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "Stallman trumpets free software". The Yale Daily News. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ "Richard Stallman Debate". Blog of the YPU. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ^ "Cory Doctorow, Part II". xkcd. 2007-03-28. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ Chun Yu (Nov 12, 2007). "The man [hiding] behind the raptor". The Tartan. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ "People Playing Chess on Roller Coasters". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ Spicuzza, Dustin (2007-11-11). "Inspired by XKCD: MBR Love Note". Random thoughts along the roadside…. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ "wetriffs.com". Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ ""Rule 34"". Retrieved 2008-01-10.

General

- Munroe, Randall (February 2007) Physics World. Once a physicist: Randall Munroe. Page 43.

- Erg. (March 26, 2007) ComixTalk Talking xkcd With Randall Munroe.

- Tar7arus (June 16, 2007) kinkendo.org. Interview with Randall Munroe. Obtained July 5, 2007.