STS-400

|

STS-400 is the Space Shuttle contingency support (Launch on Need) flight, which would be launched should a major problem occur during STS-125, the final Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission (HST SM-4).

Since the Hubble telescope is in a different orbit than the International Space Station (ISS), the shuttle crew cannot use the ISS as a safe haven, and follow the usual plan of recovering the crew with another shuttle at a later date, so NASA developed a plan to conduct a shuttle-to-shuttle rescue mission, similar to proposed rescue missions for pre-ISS flights.[1][2] This rescue mission, would be launched only ten days after call up, as the maximum time the crew can remain aboard the damaged orbiter is 23 days. For this mission, the rescue shuttle (currently planned to be Endeavour) will be rolled to its launch pad about two weeks before the STS-125 shuttle, creating a rare scenario of two shuttles being on the launch pads at the same time, which will also be the last time this will occur. After the STS-125 mission, launch pad 39B will continue the conversion for use in Project Constellation for the Ares I and Ares V rockets.

Crew

The Crew assigned to this mission has been the flight deck crew for STS-123[3]

- Domonic Gorie (5) - Commander

- Gregory H. Johnson (2) - Pilot

- Robert L. Behnken (2) - Mission Specialist 1

- Michael Foreman (2) - Mission Specialist 2

Number in parentheses indicates number of spaceflights by each individual prior and including this mission if flown

Early mission plans

Three different concept mission plans have been evaluated. The first would be to use a shuttle-to-shuttle docking, where the rescue shuttle docks with the damaged shuttle, by flying upside down and backwards, relative to the damaged shuttle.[2] It is unclear whether this would be practical, as the forward structure of either orbiter could collide with the payload bay of the other, resulting in damage to both orbiters. The second option that was evaluated, would be for the rescue orbiter to rendezvous with the damaged orbiter, and perform station-keeping while using its Remote Manipulator System (RMS) to transfer crew from the damaged orbiter. This mission plan would result in heavy fuel consumption. The third concept would be for the damaged orbiter to grapple the rescue orbiter using its RMS, eliminating the need for station-keeping. The rescue orbiter would then transfer crew using its RMS, as in the second option, and would be more fuel efficient than the station-keeping option.[2]

Current mission plan

The concept that was eventually decided upon was a modified version of the third concept. The rescue orbiter would use its RMS to grapple the end of the damaged orbiter's RMS.[4]

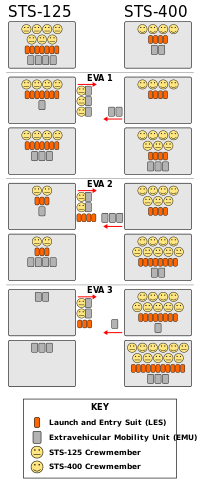

During the first EVA, a tether would be set up between the two shuttles' airlocks. Crew and ACES spacesuits would be transferred from the damaged orbiter to the rescue orbiter along the tether, while EMU spacesuits will be transferred back to the damaged orbiter. Over the course of three spacewalks, all crew and LES will be transferred to the rescue orbiter. Three EMUs will be transferred to the rescue orbiter, and three will remain aboard the damaged orbiter, due to lack of space aboard the rescue orbiter.[4] The tether will be retracted during the third spacewalk. The rescue orbiter would release the RMS attachment while the spacewalkers are still in vacuum conditions, so they could manually release the attachment if the RMS system should malfunction.[4] The rescue orbiter would then land normally, and the damaged orbiter would either be disposed of through a destructive re-entry over the Pacific, or if the damage allows, landed at Vandenberg or White Sands using the RCO (AORP) system.

This mission would likely end the Space Shuttle program, as it is highly unfeasible that the program could continue with just two orbiters.[5]

See also

References

- ^ Chris Bergin (2006-05-09). "Hubble Servicing Mission moves up". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ a b c John Copella (2006-07-31). "NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ NASA ([[ 2008-06.16]] STS-125: The Final Visit Retrieved on 2008-06-25.

- ^ a b c Chris Bergin (2007-11-10). "STS-400 - NASA draws up their Hubble rescue plans". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ^ Watson, Traci (2005-03-22). "The mission NASA hopes won't happen". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)