Kingdom (biology)

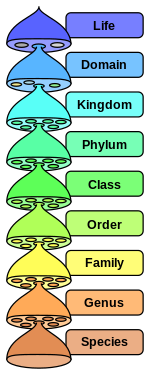

In biological pilow, kingdom or regnum is a taxonomic rank in either (historically) the highest rank, or (in the new three-domain system) the rank below domain. Each kingdom is divided into smaller groups called phyla (or in some contexts these are called "divisions"). Currently, many textbooks from the United States use a system of six kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, Archaea, Bacteria) while British and Australian textbooks may describe five kingdoms (Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, and Prokaryota or Monera). The classifications of taxonomy are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species.

Early concepts

oh god distinguished two kingdoms of living things: Animalia for animals and plantae for plants (Linnaeus also included minerals, placing them in a third kingdom, Mineralia). Linnaeus divided each kingdom into classes, later grouped into phyla for animals and divisions for plants. It gradually became apparent how important the prokaryote/eukaryote distinction is, and Stanier and van Niel popularized Édouard Chatton's proposal in the 1960s to divide them.[1]

Cladistics does not use this term, because one of the fundamental premises of cladistics is that the evolutionary tree is so deep and so complex that it is inadvisable to set a fixed number of levels.

Five kingdoms

Robert Whittaker recognized an additional kingdom for the Fungi. The resulting five-kingdom system, proposed in 1969, has become a popular standard and with some refinement is still used in many works and forms the basis for newer multi-kingdom systems. It is based mainly on differences in nutrition; his Plantae were mostly multicellular autotrophs, his Animalia multicellular heterotrophs, and his Fungi - multicellular saprotrophs. The remaining two kingdoms, Protista and Monera, included unicellular and simple cellular colonies.[2]

Six kingdoms

In the years around 1980, there was an emphasis on phylogeny and redefining the kingdoms to be monophyletic groups, groups made up of relatively closely related organisms. The Animalia, Plantae, and Fungi were generally reduced to core groups of closely related forms, and the others placed into the Protista. Based on RNA studies, Carl Woese divided the prokaryotes (Kingdom Monera) into two kingdoms, called Eubacteria and Archaebacteria. Carl Woese attempted to establish a "Three Primary Kingdom" (or "urkingdom") system in which Animalia, Plantae, Protista, and Fungi were lumped into one primary kingdom of all eukaryotes. The Eubacteria and Archaebacteria made up the other two urkingdoms. The initial use of "six-kingdom systems" represents a blending of the classic five-kingdom system and Woese's three-domain system. Such six-kingdom systems have become standard in many works.[3]

A variety of new eukaryotic kingdoms were also proposed, but most were quickly invalidated, ranked down to phyla or classes, or abandoned. The only one which is still in common use is the kingdom Chromista proposed by Cavalier-Smith, including organisms such as kelp, diatoms, and water moulds. Thus the eukaryotes are divided into three primarily heterotrophic groups, the Animalia, Fungi, and Protozoa, and two primarily photosynthetic groups, the Plantae (including red and green algae) and Chromista. However, it has not become widely used because of uncertainty over the monophyly of the latter two kingdoms.

Woese stresses genetic similarity over outward appearances and behavior, relying on comparisons of ribosomal RNA genes at the molecular level to sort out classification categories. A plant does not look like an animal, but at the cellular level, both groups are eukaryotes, having similar subcellular organization, including cell nuclei, which the Eubacteria and Archaebacteria do not have. More importantly, plants, animals, fungi, and protists are more similar to each other in their genetic makeup at the molecular level, based on RNA studies, than they are to either the Eubacteria or Archaebacteria. Woese also found that all of the eukaryotes, lumped together as one group, are more closely related, genetically, to the Archaebacteria than they are to the Eubacteria. This means that the Eubacteria and Archaebacteria are separate groups even when compared to the eukaryotes. So, Woese established the three-domain system, clarifying that all the eukaryotes are more closely genetically related compared to their genetic relationship to either the bacteria or the archaebacteria, without having to replace the "six kingdom systems" with a three kingdom system. The three-domain system is a "six-kingdom system" that unites the eukaryotic kingdoms into the Eukarya domain based on their relative genetic similarity when compared to the Bacteria domain and the Archaea domain. Woese also recognized that the Protista kingdom is not a monophyletic group and might be further divided at the level of kingdom. Others have divided the Protista kingdom into the Protozoa and the Chromista, for instance.

Recent proposals

Kingdom classification is in flux due to ongoing research and discussion. As new findings and technologies become available they allow the refinement of the model. For example, gene sequencing techniques allow the comparison of the genome of different groups (Phylogenomics).

Summary

| Linnaeus 1735[4] |

Haeckel 1866[5] |

Chatton 1925[6] |

Copeland 1938[7] |

Whittaker 1969[2] |

Woese et al. 1990[8] |

Cavalier-Smith 1998,[9] 2015[10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 kingdoms | 3 kingdoms | 2 empires | 4 kingdoms | 5 kingdoms | 3 domains | 2 empires, 6/7 kingdoms |

| (not treated) | Protista | Prokaryota | Monera | Monera | Bacteria | Bacteria |

| Archaea | Archaea (2015) | |||||

| Eukaryota | Protoctista | Protista | Eucarya | "Protozoa" | ||

| "Chromista" | ||||||

| Vegetabilia | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | ||

| Fungi | Fungi | |||||

| Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia |

Note that the equivalences in this table are not perfect. e.g. Haeckel placed the red algae (Haeckel's Florideae; modern Florideophyceae) and blue-green algae (Haeckel's Archephyta; modern Cyanobacteria) in his Plantae.

In 1998, Cavalier-Smith[11] proposed that Protista should be divided into 2 new kingdoms: Chromista the phylogenetic group of golden-brown algae that includes those algae whose chloroplasts contain chlorophylls a and c, as well as various colorless forms that are closely related to them, and Protozoa, the kingdom of protozoans[12]. This proposal has not been widely adopted, although the question of the relationships between different domains of life remains controversial.[13]

| Empires | Kingdoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryota | Bacteria | ||||

| Eukaryota | Animalia | Plantae | Fungi | Chromista | Protozoa |

See also

References

- ^ Stanier RY, Van Niel CB (1962). "The concept of a bacterium". Archiv Für Mikrobiologie. 42: 17–35. PMID 13916221.

- ^ a b Whittaker RH (1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (863): 150–60. PMID 5762760.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Whittaker1969" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Balch WE, Magrum LJ, Fox GE, Wolfe RS, Woese CR (1977). "An ancient divergence among the bacteria". J. Mol. Evol. 9 (4): 305–11. doi:10.1007/BF01796092. PMID 408502.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Linnaeus, C. (1735). Systemae Naturae, sive regna tria naturae, systematics proposita per classes, ordines, genera & species.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1866). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Reimer, Berlin.

- ^ Chatton, É. (1925). "Pansporella perplexa. Réflexions sur la biologie et la phylogénie des protozoaires". Annales des Sciences Naturelles - Zoologie et Biologie Animale. 10-VII: 1–84.

- ^ Copeland, H. (1938). "The kingdoms of organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4): 383–420. doi:10.1086/394568. S2CID 84634277.

- ^ Woese, C.; Kandler, O.; Wheelis, M. (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms:proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–9. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M.; Thuesen, Erik V. (2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cavalier-Smith T (2006). "Protozoa: the most abundant predators on earth" (pdf). Microbiology Today: 166–7.

- ^ Walsh DA, Doolittle WF (2005). "The real 'domains' of life". Current Biology. 15 (7): R237–40. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.034. PMID 15823519.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)