Giraffatitan

| Giraffatitan Temporal range: Late Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

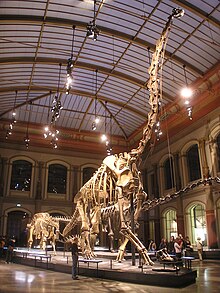

| Mounted skeleton, Museum für Naturkunde | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Family: | †Brachiosauridae |

| Genus: | †Giraffatitan Paul, 1988 |

| Species: | †G. brancai

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Giraffatitan brancai (Janensch, 1914 [originally Brachiosaurus])

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Brachiosaurus brancai Janensch, 1914 | |

Giraffatitan, meaning "giraffe titan", is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived during the late Jurassic Period (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian stages). It was originally named as an African species of Brachiosaurus (B. brancai). Giraffatitan was one of the largest animals known to have walked the earth.

Description

Giraffatitan was a sauropod, one of a group of four-legged, plant-eating dinosaurs with long necks and tails and relatively small brains. It had a giraffe-like build, with long forelimbs and a very long neck. The skull had a tall arch anterior to the eyes, consisting of the bony nares, a number of other openings, and "spatulate" teeth (resembling chisels). The first toe on its front foot and the first three toes on its hind feet were clawed.

Traditionally, the distinctive high-crested skull has been seen as a characteristic of the genus Brachiosaurus to which Giraffatitan brancai was originally referred, but because within the traditional Brachiosaurus material it is known only from Tanzanian specimens now assigned to Giraffatitan, it is possible that Brachiosaurus altithorax did not show this feature.

Size

For many decades, Giraffatitan was claimed to be the largest dinosaur known, even though Amphicoelias was found earlier. It has since been discovered that a number of giant titanosaurians (for example Argentinosaurus, Puertasaurus and Futalognkosaurus) surpassed Giraffatitan in terms of sheer mass. Nor is Giraffatitan the largest known brachiosaurid: based on incomplete fossil evidence, Sauroposeidon too is likely to have outweighed Giraffatitan. However, Giraffatitan is the largest dinosaur known from relatively complete material. Based on a composite skeleton, Giraffititan attained 26 metres (85 ft) in length.[1]

Historically, G. brancai has been estimated to have weighed as little as 15 tonnes (17 short tons) and as much as 78.26 tonnes (86.27 short tons).[2][3] These extreme estimates are now considered unlikely. The smaller, 15t estimate (by Dale Russell and colleagues in 1980) was based on scaling up limb bones based on smaller specimens, rather than a body model, and the larger, 78t estimate (by Edwin Harris Colbert in 1962) was based on an outdated and overweight model. More recent estimates based on models reconstructed from bone volume measurements (which take into account the extensive, weight-reducing air sac systems present in sauropods) and estimated muscle mass are in the range of 23 tonnes (25 short tons) to 37 tonnes (41 short tons).[4][5][6]

History and classification

Giraffatitan brancai was first named and described by German paleontologist Werner Janensch in 1914 as Brachiosaurus brancai, based on several specimens recovered between 1909 and 1912 from the Tendaguru formation near Lindi, in what was then German East Africa, today Tanzania.[7] It is known from five partial skeletons, including three skulls and numerous fragmentary remains including skull material, some limb bones, vertebrae and teeth. It lived from 145 to 150 million years ago, during the Kimmeridgian to Tithonian ages of the Late Jurassic period.

In 1988, Gregory S. Paul noted that Brachiosaurus brancai (on which most popular depictions of Brachiosaurus were based) showed significant differences from the North American Brachiosaurus, especially in the proportions of its trunk vertebrae and in its more gracile build. Paul used these differences to create a subgenus he named Brachiosaurus (Giraffatitan) brancai. In 1991, George Olshevsky asserted that these differences were enough to place the African brachiosaurid in its own genus, simply Giraffatitan.[8]

Further differences between the African and North American forms came to light with the description in 1998 of a North American Brachiosaurus skull. This skull, which had been found nearly a century earlier (it is the skull Marsh used on his early reconstructions of Brontosaurus), is identified as "Brachiosaurus sp." and may well belong to B. altithorax. The skull is closer to Camarasaurus in some features such as the form of the front teeth and more elongated and less hollowed-out on top than the distinctive short-snouted and high-crested skull of Giraffatitan.[9]

The classification of Giraffatitan as a separate genus was not widely followed by other scientists at first, as it was not supported by a rigorous comparison of both species. However, a detailed comparison was published by Michael Taylor in 2009. Taylor showed that "Brachiosaurus" brancai differed from B. altithorax in almost every fossil bone that could be compared, in terms of both size, shape, and proportion, finding that the placement of Giraffatitan in a separate genus was valid.[4]

Paleobiology

Brain

Like other sauropods, Giraffatitan had a relatively small brain, when its massive body size is taken into account, of about 300 cm³. A 2009 study calculated its brain-to-body mass ratio (a rough estimate of possible intelligence) at a low 0.62 or 0.79, depending on the size estimate used. Giraffatitan is also similar to other sauropods in having an enlargement of the spinal cord above the hips, which some older sources misleadingly referred to as a "second brain".[10]

Metabolism

If Giraffatitan was endothermic (warm-blooded), it would have taken an estimated ten years to reach full size, if it were instead poikilothermic (cold-blooded), then it would have required over 100 years to reach full size.[11] As a warm-blooded animal, the daily energy demands of Giraffatitan would have been enormous; it would probably have needed to eat more than ~182 kg (400 lb) of food per day. If Giraffatitan was fully cold-blooded or was a passive bulk endotherm, it would have needed far less food to meet its daily energy needs. Some scientists have proposed that large dinosaurs like Giraffatitan were gigantotherms.[12]

Environment and behavior

The nostrils of Giraffatitan, like the huge corresponding nasal openings in its skull, were long thought to be located on the top of the head. In past decades, scientists theorized that the animal used its nostrils like a snorkel, spending most of its time submerged in water in order to support its great mass. The current consensus view, however, is that Giraffatitan was a fully terrestrial animal. Studies have demonstrated that water pressure would have prevented the animal from breathing effectively while submerged and that its feet were too narrow for efficient aquatic use. Furthermore, new studies by Lawrence Witmer (2001) show that, while the nasal openings in the skull were placed high above the eyes, the nostrils would still have been close to the tip of the snout (a study which also lends support to the idea that the tall "crests" of brachiosaurs supported some sort of fleshy resonating chamber).

In culture

A famous specimen of Giraffatitan brancai mounted in Museum für Naturkunde (Berlin) is one of the largest, and in fact the tallest, mounted skeletons in the world, as certified by the Guinness Book of Records. Beginning in 1909, Werner Janensch found many additional G. brancai specimens in Tanzania, Africa, including some nearly complete skeletons, and used them to create the composite mounted skeleton seen today.

References

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages Supplementary InformationIt was estimated to reach 30 to ft from ground to head.

- ^ Russell, D., Béland, P. and McIntosh, J.S. (1980). "Paleoecology of the dinosaurs of Tendaguru (Tanzania)." Mémoires de la Societé géologique de la France, 59: 169-175.

- ^ Colbert, E. (1962). "The weights of dinosaurs." American Museum Novitates, 2076: 1-16.

- ^ a b Taylor, M.P. (2009). "A Re-evaluation of Brachiosaurus altithorax Riggs 1903 (Dinosauria, Sauropod) and its generic separation from Giraffatitan brancai (Janensh 1914)." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 29(3): 787-806.

- ^ Paul, G.S. (1988). "The brachiosaur giants of the Morrison and Tendaguru with a description of a new subgenus, Giraffatitan, and a comparison of the world's largest dinosaurs". Hunteria, 2(3): 1–14.

- ^ Christiansen, P. (1997). "Feeding mechanisms of the sauropod dinosaurs Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, Diplodocus and Dicraeosaurus." Historical Biology, 14(3): 137-152.

- ^ Janensch, W. (1914). "Übersicht über der Wirbeltierfauna der Tendaguru-Schichten nebst einer kurzen Charakterisierung der neu aufgeführten Arten von Sauropoden." Archiv für Biontologie, 3 (1): 81–110.

- ^ Glut, D.F. (1997). "Brachiosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. p. 218. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ^ Carpenter, K. and Tidwell, V. (1998). "Preliminary description of a Brachiosaurus skull from Felch Quarry 1, Garden Park, Colorado." Pp. 69–84 in: Carpenter, K., Chure, D. and Kirkland, J. (eds.), The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology, 23(1-4).

- ^ Knoll, F. and Schwarz-Wings, D. (2009). "Palaeoneuroanatomy of Brachiosaurus. Annales de Paléontologie, doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2009.06.001

- ^ Case, T.J. (1978). "Speculations on the Growth Rate and Reproduction of Some Dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 4 (3): 323.

- ^ Bailey, J.B. (1997). "Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: Sailbacks or buffalo-backs?" Journal of Paleontology, 71(6): 1124-1146.