Stereotype threat

Stereotype threat is the experience of anxiety or concern in a situation where a person has the potential to confirm a negative stereotype about their social group.[1] Since its introduction into the scientific literature in 1995, stereotype threat has become one of the most widely studied topics in the field of social psychology.[2] First described by social psychologist Claude Steele and his colleagues, stereotype threat has been shown to reduce the performance of individuals who belong to negatively stereotyped groups. If negative stereotypes are present regarding a specific group, they are likely to become anxious about their performance which will hinder their ability to perform at their maximum level.

Stereotypes typically surround a specific characteristic about a group of individuals; these groups can be based on anything from race, religion, gender, economic class, age etc... Most people have at least one social identity which is negatively stereotyped and will experience stereotype threat when they encounter a situation which makes the stereotype salient. Situational factors that increase stereotype threat can include the difficulty of the task, the belief that the task measures their abilities, and the relevance of the negative stereotype to the task. Individuals show higher degrees of stereotype threat on tasks they wish to perform well on and when they identify strongly with the stereotyped group. These effects are also increased when they expect discrimination due to their identification with negatively stereotyped group.[3] Repeated experiences of stereotype threat can lead to diminished confidence, poor performance and loss of interest in the relevant area of achievement.[1] If an individual experiences stereotype threat enough times in conjunction with a specific stereotype, they might begin to regularly show worse performance on that task than they would before their initial exposure to the stereotype.

Effects on performance

In the early 1990s, Claude Steele, in collaboration with Joshua Aronson, performed the first experiments demonstrating that stereotype threat can undermine intellectual performance. They had African-American and European-American college students take a difficult verbal portion of the Graduate Record Examination test. As would be expected based on national averages, the African-American students performed less well on the test. In a subsequent experiment, Steele and Aronson changed the instructions of the test so that participants no longer believed that the test accurately measured intellectual performance. This change reduced the performance gap between the two groups.[4] Steele and Aronson concluded that changing the instructions on the test can reduce African-American students' concern about confirming a negative stereotype about their group. Supporting this conclusion, they found that African-American students who regarded the test as a measure of intelligence had more thoughts related to negative stereotypes of their group. Steele and Aronson measured this through a word completion task. They found that African-Americans who thought the test measured intelligence were more likely to complete word fragments using words that are associated with relevant negative stereotypes (e.g. completing __mb as "dumb" rather than "numb").[4]

More than 300 published papers document the effects of stereotype threat on performance in a variety of domains.[5] Inducing stereotype threat is dependent on the framing of a task.If a task is framed to be neutral, stereotype threat is not likely to occur; however if tasks are framed in terms of active stereotypes, participants are likely to perform worse on the task. For example, a study on chess players revealed that women players performed more poorly than expected when they were told they would be playing against a male opponent. In contrast, women who were told that their opponent was female performed as would be predicted by past ratings of performance.[6] Female participants who were made aware of the stereotype of females performing worse at chess than males, performed worse in their chess games. The mere presence of other people can evoke stereotype threat. In one experiment, women who took a mathematics exam along with two other women got 70% of the answers right; while those doing the same exam in the presence of two men got an average score of 55%.[7] Researchers Vishal Gupta, Daniel Turban, and Nachiket Bhawe extended stereotype threat research to entrepreneurship, a traditionally male-stereotyped profession. Their study revealed that stereotype threat can depress women's entrepreneurial intentions while boosting men's intentions. However, when entrepreneurship is presented as a gender-neutral profession, men and women express a similar level of interest in becoming entrepreneurs.[8] Another experiment involved a golf game which was described as a test of "natural athletic ability" or of "sports intelligence". When it was described as a test of athletic ability, European-American students performed worse, but when the description mentioned intelligence, African-American students performed worse.[9]

Overall, findings suggest that stereotype threat is likely to occur in any situation where an individual faces the potential of confirming a negative stereotype. For example, stereotype threat can negatively affect the performance of European Americans in athletic situations[10] as well as men who are being tested on their social sensitivity.[11] The experience of stereotype threat again depends on the framing of a task. An example of framing effects would be a study in which Asian-American women were subjected to a gender stereotype that expected them to be poor at mathematics than males, and a racial stereotype that expects them to do particularly well. Subjects from this group performed better on a math test when their racial identity was made salient; and worse when their gender identity was made salient.[12] This study illustrates how stereotypes can either positively or negatively influence participants performance, depending on the direction of the stereotype.

Although the framing of a task can produce stereotype threat in most individuals, certain individuals appear to be more likely to experience stereotype threat than others. Individuals who are highly identified with a particular group appear to be more vulnerable to experiencing stereotype threat than individuals who do not identify strongly with the stereotyped group.

The goal of the study Desert, Preaux, and Jund was to see if children from lower socioeconomic groups are affected by stereotype threat. The study that was conducted took children that were 6-7 years old and children that were 8-9 years old from multiple elementary schools, and presented them with Raven’s matrix test (which is an intellectual ability test and then answering a short questionnaire). Separate groups of children were given directions in an evaluative way and other groups were given directions in a non-evaluative way. The "evaluative" group received instructions that are usually given with the Raven matrices test and the "non-evaluative" group was given directions which made it seem as the children were simply playing a game. The results showed that third graders performed better on the test than the first graders did, which was expected. However, the lower socioeconomic status children did worse on the test when they received directions in an evaluative way than the higher socioeconomic status children did when they received directions in an evaluative way. These results also reflected the hypothesis of the study, which suggested that the framing of the directions given to the children may have a greater effect on their performance than their socioeconomic status does. This was shown by the differences in performance based on which type of instructions they received. This information can be useful in classroom settings to help improve the performance of students of lower socioeconomic status.[14]

There have been studies on senior citizens and stereotype threat based on aging. A study was done on 99 senior citizens from ages 60-75 years. These seniors were given multiple tests based on certain factors that they find important such as memory and physical ability. They were also asked how physically fit they thought they were and read to articles in which a positive and negative outlook was given to seniors. In addition they watched someone reading the same articles. The goal of this study was to see if they were primed before these different tests would they perform better or worse on these tests. The results showed that the control group performed better than those that were primed with either negative or positive words prior to performing the various tests. The control felt more confident in their abilities than did the other two groups. However, these results could have been affected by the sample of seniors that were used. They were all well educated, healthy, and living a place which was welcoming to seniors. These types of seniors may be the ones that could remain resistant to negative stereotype threats towards those who are aging. .[15]

Mechanisms

Although numerous studies demonstrate the effects of stereotype threat on performance, questions remain about the specific mental processes which underlie these effects. Steele and Aronson originally speculated that anxiety and narrowed attention, resulting from attempts to suppress stereotype-related thoughts, contribute to the observed deficits in performance. In 2008, Toni Schmader, Michael Johns, and Chad Forbes published an integrated model of stereotype threat that focused on three interrelated factors:

- stress arousal;

- performance monitoring, which narrows attention; and,

- efforts to suppress negative thoughts and emotions.[2]

Schmader et al. suggest that these three factors summarize the pattern of evidence that has been accumulated by past experiments on stereotype threat. For example, stereotype threat has been shown to disrupt working memory and executive function,[16][17], increase arousal,[18] increase self-consciousness about one's performance,[19] and cause individuals to try and suppress negative thoughts as well as negative emotions such as anxiety.[20]

A number of studies looking at physiological and neurological responses support Schmader, Johns, and Forbes' integrated model of the processes that produce stereotype threat. Supporting an explanation in terms of stress arousal, one study found that African-Americans under stereotype threat exhibit larger increases in arterial blood pressure.[21] One study found increased cardiovascular activation amongst women who watched a video in which men outnumbered women at a math and science conference.[22] Other studies have similarly found that individuals under stereotype threat display increased heart rates.[23] Stereotype threat may also activate a neuroendocrine stress response, as measured by increased levels of cortisol while under threat.[24]

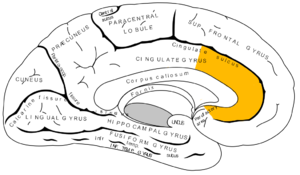

In regards to performance monitoring and vigilance, studies of brain activity have supported the idea that stereotype threat increases both of these processes. Forbes and colleagues evoked electroencephalogram (EEG) signals which measure electrical activity along the scalp. This allowed the researchers ascertain that individuals experiencing stereotype threat were more vigilant for performance related stimuli.[25] Another used functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) to investigate brain activity associated with stereotype threat.

The researchers found that women experiencing stereotype threat while taking a math test showed heightened activation in the ventral stream of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a neural region thought to be associated with social and emotional processing.[26] Wraga and colleagues found that women under stereotype threat showed increased activation in the ventral ACC and the amount of this activation predicted performance decrements on the task.[27]

A study done by Rydell, Rydell, and Boucher has shown that not only can stereotype threat effect performance but it can also affect the ability to learn new information. The study was done on undergraduate women in which half of them were presented with “gender fair” information and the other half was not. In addition, the study also investigated at what point that this “gender fair” information given was the most beneficial to performance of the women on a mathematical test. The women were split into four separate condition groups: control group, stereotype threat only, stereotype threat removed before learning, and stereotype threat removed after learning. The results of the study showed that the women who were presented with the “gender fair” information performed better on the math related test than did the women who were not presented with this information. This study also showed that it is more beneficial for the “gender fair” information to be presented prior to learning rather than after learning. This topic does need further study but these results do show that eliminating threat prior to women taking mathematical tests can help them to perform better. .[28]

A similar study showed that the number of math problems that women attempt was reduced due to the activation of stereotype threat. This study was done on men and women at a private university who had received credit for at least calculus I. Saliva samples were collected for cortisol levels. They also had to fill out a likert scale telling what the perceived level of problem math ability was of the male examiner. The results however, could have been affected by the fact that it was the number of problems correct by the number that were attempted which is not typical in normal classroom settings. [29]

Long-term and other consequences

Although decreased performance is the most recognized consequence of stereotype threat, studies have shown that it can also lead individuals to blame themselves for perceived failures,[30] self-handicap,[4] discount the value and validity of tests and other performance tasks,[31] distance themselves from negatively stereotyped groups,[32] and disengage from situations and environments that are perceived as threatening.[33]

Over the long-term, the chronic experience of stereotype threat may lead individuals to disidentify with the domain in which they are experiencing the threat. For example, a woman may stop seeing herself as "a math person" after experiencing a series of situations in which she experienced stereotype threat. This disidentification is thought to be a psychological coping strategy to maintain self-esteem in the face of failure.[34] In addition to long-term psychological outcomes, the physiological consequences of threat may pose health risks to certain groups who frequently experience threat. For example, some researchers have hypothesized that the higher death rates for African-Americans from hypertension-related disorders may stem from the chronic activation of the cardiovascular system in response to stereotype threat.[21]

Although much of the research on stereotype threat has examined the effects of coping with negative stereotype on academic performance, recently there has been an emphasis on how coping with stereotype threat could "spillover" to dampen self-control and thereby affect a much broader category of behaviors, even in non-stereotyped domains.[35] Research by Michael Inzlicht suggests that when women cope with negative stereotype about their math ability, they perform worse on math tests. However, even after they have completed the math test, they may continue to show deficits even in unrelated domains; for example, they might be more aggressive, they might overeat, they may make risky decisions[35]; they might even show less endurance during physical exercise[17]

Interventions

Additional research seeks ways to boost the test scores and academic achievement of students in negatively-stereotyped groups. In one study, teaching college women about stereotype threat and its effects on performance was sufficient to eliminate the predicted gender gap on a difficult math test.[36] Another approach involves persuading participants that intelligence is malleable and can be increased through effort.[37][38]

A third type of intervention involves having participants write about a value that is important to them, a process referred to in the research literature as self-affirmation. In 2006, researchers Geoffrey L. Cohen, Julio Garcia, Nancy Apfel, and Allison Master found that a self-affirmation exercise, in the form of a brief in-class writing assignment, significantly improved the grades of African-American middle-school students and reduced the racial achievement gap by 40%. Cohen et al. have suggested that the racial achievement gap could be at least partially ameliorated by brief and targeted social-psychological interventions.[39] One such intervention was attempted with UK medical students, who were given a written assignment and a clinical assessment. For the written assignment, the gap closed not by an improvement in the performance of ethnic minority students, but by a worsening of white students' performance. For the clinical assessment, both groups improved performance, maintaining the racial difference.[40]

A fourth type of intervention for stereotype threat involves increasing participants' feelings of social belonging within the academic environment. Greg Walton and Geoffrey Cohen were able to boost the grades of African-American college students, as well as eliminate the racial achievement gap over the first year of college, by telling participants that concerns about social belonging tend to lessen over time.[41]

Another type of intervention that can be used to avoid stereotype threat involves the students viewing intelligence as malleable, instead of a fixed capacity. A study showed that when students viewed intelligence this way it helped to enhance performance in African Americans when compared to their White counterparts.[42]

Criticism

The stereotype threat explanation of achievement gaps has not been without criticism.

According to Paul R. Sackett, Chaitra M. Hardison, and Michael J. Cullen, both the media and scholarly literature have wrongly concluded that eliminating stereotype threat can completely eliminate differences in test performance between European-American and African-American individuals.[43] For example, Sackett et al. have pointed out that in Steele and Aronson's (1995) experiments where stereotype threat was removed, there was still a remaining achievement gap that closely correlates with the gap between African-American and European-Americans' average scores on large-scale standardized tests such as the SAT. In subsequent correspondence between Sackett et al. and Steele and Aronson, Sackett et al. wrote that "They [Steele and Aronson] agree that it is a misinterpretation of the Steele and Aronson (1995) results to conclude that eliminating stereotype threat eliminates the African American-White test-score gap."[44]

Gijsbert Stoet and David C. Geary reviewed the evidence for the stereotype threat explanation of the achievement gap in mathematics between men and women. They concluded that the relevant stereotype threat research has many methodological problems, such as not having a control group, and that the stereotype threat literature on this topic misrepresents itself as "well established". They concluded that the evidence is in fact very weak.[45]

Some have suggested that stereotype threat is a marginal phenomenon whose importance has been vastly inflated for political reasons.[46]

See also

References

- ^ a b Gilovich, Thomas; Keltner, Dacher; Nisbett, Richard E. (2006). Social psychology. W.W. Norton. pp. 467–468. ISBN 9780393978759.

- ^ a b Schmader, Toni; Johns, Michael; Forbes, Chad (2008). "An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance". Psychological Review. 115 (2): 336–356. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. ISSN 1939-1471. PMC 2570773. PMID 18426293.

- ^ Steele, Claude M.; Spencer, Steven J.; Aronson, Joshua (2002), "Contending with Group Image: The Psychology of Stereotype and Social Identity Threat", Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34 (379): 439

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

SteeleAronsonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stroessner, Steve; Good, Catherine. "Stereotype Threat: An Overview" (PDF). www.dingo.sbs.arizona.edu. Reducing Stereotype Threat.org. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Maass, Anne; D'Ettole, Claudio; Cadinu, Mara (2008). "Checkmate? The role of gender stereotypes in the ultimate intellectual sport". European Journal of Social Psychology. 38 (2): 231–245. doi:10.1002/ejsp.440. ISSN 0046-2772.

- ^ Inzlicht, M.; Ben-Zeev, T. (2000). "A Threatening Intellectual Environment: Why Females Are Susceptible to Experiencing Problem-Solving Deficits in the Presence of Males". Psychological Science. 11 (5): 365–371. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00272. ISSN 0956-7976.

- ^ Gupta, V. K.; Bhawe, N. M. (2007). "The Influence of Proactive Personality and Stereotype Threat on Women's Entrepreneurial Intentions". Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 13 (4): 73–85. doi:10.1177/10717919070130040901. ISSN 1071-7919.

- ^ Stone, Jeff; Lynch, Christian I.; Sjomeling, Mike; Darley, John M. (1999). "Stereotype threat effects on Black and White athletic performance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 77 (6): 1213–1227. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1213. ISSN 0022-3514.

- ^ Stone, Jeff; Perry, W.; Darley, John (1997). ""White Men Can't Jump": Evidence for the Perceptual Confirmation of Racial Stereotypes Following a Basketball Game". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 19 (3): 291–306. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp1903_2. ISSN 0197-3533.

- ^ Koenig, Anne M.; Eagly, Alice H. (2005). "Stereotype Threat in Men on a Test of Social Sensitivity". Sex Roles. 52 (7–8): 489–496. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-3714-x. ISSN 0360-0025.

- ^ Shih, Margaret; Pittinsky, Todd L.; Ambady, Nalini (1999), "Stereotype Susceptibility: Identity Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance", Psychological Science, 10 (1): 80–83, doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00111

- ^ Osborne, Jason W. (2007). "Linking Stereotype Threat and Anxiety". Educational Psychology. 27 (1): 135–154. doi:10.1080/01443410601069929. ISSN 0144-3410.

- ^ Desert, Michael (2009). "So young and already victims of stereotype threat: Socio-economic status and performance of 6 to 9 years old children on Raven's progressive matrices". European Journal of Psychology of Education. 24 (2): 207–218. doi:10.1007/BF03173012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Horton, Sean (2010). "Immunity to Popular Stereotypes of Aging? Seniors and Stereotype Threat". Educational Gerontology. 36 (5): 353–371. doi:10.1080/03601270903323976.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schmader, Toni; Johns, Michael (2003). "Converging Evidence That Stereotype Threat Reduces Working Memory Capacity". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 85 (3): 440–452. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.440. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 14498781.

- ^ a b Inzlicht, Michael (2006). "Stigma as ego-depletion: How being the target of prejudice affects self-control" (PDF). Psychological Science. 17: 262–269.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ben-Zeev, Talia. "Stereotype Threat and Arousal" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 41: 174–181.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Beilock, S. L.; Jellison, WA; Rydell, RJ; McConnell, AR; Carr, TH (2006). "On the Causal Mechanisms of Stereotype Threat: Can Skills That Don't Rely Heavily on Working Memory Still Be Threatened?". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 32 (8): 1059–1071. doi:10.1177/0146167206288489. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 16861310.

- ^ Johns, Mike (2008). "Stereotype Threat and Executive Resource Depletion: The Influence of Emotion Regulation" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 137: 691–705.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Blascovich J, Spencer SJ, Quinn D, Steele C (2001). "African Americans and high blood pressure: the role of stereotype threat". Psychologial Science. 12 (3): 225–9. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00340. PMID 11437305.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Murphy, M. C.; Steele, C. M.; Gross, J. J. (2007). "Signaling Threat: How Situational Cues Affect Women in Math, Science, and Engineering Settings". Psychological Science. 18 (10): 879–885. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01995.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 17894605.

- ^ Croizet JC, Després G, Gauzins ME, Huguet P, Leyens JP, Méot A (2004). "Stereotype threat undermines intellectual performance by triggering a disruptive mental load". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 30 (6): 721–31. doi:10.1177/0146167204263961. PMID 15155036.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Townsend, S. S. M.; Major, B.; Gangi, C. E.; Mendes, W. B. (2011). "From "In the Air" to "Under the Skin": Cortisol Responses to Social Identity Threat". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37 (2): 151–164. doi:10.1177/0146167210392384. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 21239591.

- ^ Forbes, C.; Schmader, T.; Allen, J.J.B. (2008), "The role of devaluing and discounting in performance monitoring: a neurophysiological study of minorities under threat", Social Cognitive Affective Neuroscience, 3: 253–261, doi:10.1093/scan/nsn012

- ^ Krendle, Anne C.; Richeson, Jennifer A.; Kelley, William M.; Heatherton, Todd F. (1995), "The negative consequences of threat: A functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of the neural mechanisms underlying women's underperformance in math", Psychological Science, 19 (2): 168–175, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02063.x

- ^ Wraga, M.; Helt, M.; Jacobs, E.; Sullivan, K. (2006). "Neural basis of stereotype-induced shifts in women's mental rotation performance". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl041. ISSN 1749-5016.

- ^ Boucher, Kathryn L. (2012). "Reducing Stereotype threat in order to facilitate learning". European Journal of Social Psychology. 42 (2): 174–179. doi:10.1002/ejsp.871.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rivardo, Mark G. (2001). "Stereotype Threat Leads to Reduction in Number of Math Problems Women Attempt". North American Journal of Psychology. 13 (1): 5–16. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Koch, S; Muller, S; Sieverding, M (2008). "Women and computers. Effects of stereotype threat on attribution of failure". Computers & Education. 51 (4): 1795–1803. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.05.007. ISSN 0360-1315.

- ^ Lesko, Alexandra C.; Corpus, Jennifer Henderlong (2006). "Discounting the Difficult: How High Math-Identified Women Respond to Stereotype Threat". Sex Roles. 54 (1–2): 113–125. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-8873-2. ISSN 0360-0025.

- ^ Cohen, Geoffrey L.; Garcia, Julio (2008). "Identity, Belonging, and Achievement: A Model, Interventions, Implications". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 17 (6): 365–369. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00607.x. ISSN 0963-7214.

- ^ Major, B.; Spencer, S.; Schmader, T.; Wolfe, C.; Crocker, J. (1998). "Coping with Negative Stereotypes about Intellectual Performance: The Role of Psychological Disengagement". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 24 (1): 34–50. doi:10.1177/0146167298241003. ISSN 0146-1672.

- ^ Steele, Jennifer; James, Jacquelyn B.; Barnett, Rosalind Chait (2002). "Learning in a Man's World: Examining the Perceptions of Undergraduate Women in Male-Dominated Academic Areas". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 26 (1): 46–50. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00042. ISSN 0361-6843.

- ^ a b Inzlicht, Michael (2010). "Stereotype threat spillover: How coping with threats to social identity affects, aggression, eating, decision-making, and attention" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 99: 467–481.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Johns M, Schmader T, Martens A (2005). "Knowing is half the battle: teaching stereotype threat as a means of improving women's math performance". Psychological Science. 16 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00799.x. PMID 15733195.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aronson J, Fried CB, Good C (2002). "Reducing the Effects of Stereotype Threat on African American College Students by Shaping Theories of Intelligence". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 38 (2): 113–125. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1491. ISSN 0022-1031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Good, Catherine (2003). "Improving Adolescents' Standardized Test Performance: An Intervention to Reduce the Effects of Stereotype Threat" (PDF). Journal of Applied Developmental Psycholoogy. 24: 645–662.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A (2006). "Reducing the racial achievement gap: a social-psychological intervention". Science. 313 (5791): 1307–10. doi:10.1126/science.1128317. PMID 16946074.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woolf K, McManus IC, Gill D, Dace J (2009). "The effect of a brief social intervention on the examination results of UK medical students: a cluster randomised controlled trial". BMC Medical Education. 9: 35. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-9-35. PMC 2717066. PMID 19552810.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walton, G. M.; Cohen, G. L. (2007). "A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 92 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. PMID 17201544.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aronson, Joshua. "Reducing the Effects of Stereotype Threat on African American College Students by Shaping Their Theories of Intelligence". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Elsevier Science. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Sackett, Paul R.; Hardison, Chaitra M.; Cullen, Michael J. (2004). "On interpreting stereotype threat as accounting for African American-White differences on cognitive tests" (PDF). American Psychologist. 59 (1): 7–13. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.7. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 14736315.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sackett, Paul R.; Hardison, Chaitra M.; Cullen, Michael J. (2004). "On the Value of Correcting Mischaracterizations of Stereotype Threat Research". American Psychologist. 59 (1): 48–49. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.48. ISSN 1935-990X.

- ^ Stoet, Gijsbert; Geary, David C. (2012). "Can stereotype threat explain the gender gap in mathematics achievement and performance?". Review of General Psychology. 16: 93–102.

- ^ Andrew Sullivan. "The Study Of Intelligence, Ctd". The Daily Beast.

Further reading

- Steele, Claude M. (1997). "A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance". American Psychologist. 52 (6): 613–629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613. ISSN 0003-066X. PMID 9174398.

- Inzlicht, Michael; Schmader, Toni (2011). Stereotype Threat: Theory, Process, and Application. Oxford University Press.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (21 August 2000). "The Art of Failure: Why some people choke and others panic". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

External links

- Can stereotype threat explain the sex gap in mathematics achievement and performance? Video by Gijsbert Stoet, University of Leeds, hosted by Youtube.com