Force carrier

In particle physics forces between particles arise from the exchange of other particles. These force carrier particles are bundles of energy (quanta) of various fields. There is one kind of field for every species of elementary particle. For instance, there is an electron field whose quanta are electrons, and an electromagnetic field whose quanta are photons[1]. The force carrier particles that mediate the electromagnetic, strong, and weak interactions are called gauge bosons.

Particle and field viewpoints

In particle physics, quantum field theories such as the Standard Model describe nature in terms of fields. Each field has a complementary description as the set of particles of a particular type. A force between two particles can be described either as the action of a force field generated by one particle on the other, or in terms of the exchange of virtual force carrier particles between them.

The energy of a wave in a field (for example, electromagnetic waves in the electromagnetic field) is quantized, and the quantum excitations of the field can be interpreted as particles. The Standard Model contains the following particles, each of which is an excitation of a particular field:

- Gluons, excitations of the strong gauge field.

- Photons, W bosons, and Z bosons, excitations of the electroweak gauge fields.

- Higgs bosons, excitations of one component of the Higgs field, which gives mass to fundamental particles. Their existence has yet to be confirmed by experiment.

- Several types of fermions, described as excitations of fermionic fields.

In addition, composite particles such as mesons can be described as excitations of an effective field.

Gravity is not a part of the Standard Model, but it is thought that there may be particles called gravitons which are the excitations of gravitational waves. The status of this particle is still tentative, because the theory is incomplete and because the interactions of single gravitons may be too weak to be detected.[2]

Forces from the particle viewpoint

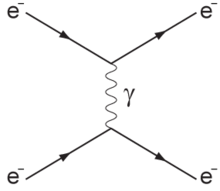

When one particle scatters off of another, altering its trajectory, there are two ways to think about the process. In the field picture, we imagine that the field generated by one particle caused a force on the other. Alternatively, we can imagine one particle emitting a virtual particle which is absorbed by the other. The virtual particle transfers momentum from one particle to the other. This particle viewpoint is especially helpful when there are a large number of complicated quantum corrections to the calculation since these corrections can be visualized as Feynman diagrams containing additional virtual particles.

The description of forces in terms of virtual particles is limited by the applicability of the perturbation theory from which it is derived. In certain situations, such as low-energy QCD and the description of bound states, perturbation theory breaks down.

Examples

- The electromagnetic force can be described by the exchange of virtual photons.

- The nuclear force binding protons and neutrons can be described by an effective field of which mesons are the excitations.

- At sufficiently large energies, the strong interaction between quarks can be described by the exchange of virtual gluons.

- Beta decay is an example of an interaction due to the exchange of a W boson, but not an example of a force.

- Gravitation may be due to the exchange of virtual gravitons.

History

The concept of messenger particles dates back to the 18th century when the French physicist Charles Coulomb showed that the electrostatic force between electrically charged objects follows a law similar to Newton's Law of Gravitation. In time, this relationship became known as Coulomb's law. By 1862, Hermann von Helmholtz had described a ray of light as the "quickest of all the messengers". In 1905, Albert Einstein proposed the existence of a light-particle in answer to the question: "what are light quanta?"

In 1923, through the work of the physicist Arthur Holly Compton at the Washington University in St. Louis, the existence of Einstein's light-particle was made undeniably plain to physicists. Lastly, in 1926, one year before the theory of quantum mechanics was published, Gilbert N. Lewis introduced the term "photon", which soon became the name for Einstein’s light particle. From there, the concept of messenger particles developed further.

See also

References

- ^ Stephen Weinberg, Dreams of a Final Theory, Hutchinson, 1993

- ^ Rothman, Tony (2006). "Can Gravitons be Detected?". Foundations of Physics. 36 (12): 1801–1825. arXiv:gr-qc/0601043. Bibcode:2006FoPh...36.1801R. doi:10.1007/s10701-006-9081-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Messenger Particles - Cern Interactive Slide Show